Is Math a STEM Afterthought?

I’ve invited Martha to be a guest author here and to offer some of the perspective she and Scott share about math’s place in the STEM movement in America. – Anne Jolly

by Martha Riecks

“The biggest problem in education is the giving of answers to questions that have not yet been asked.”

That’s a wise phrase, and a core concept that was a driving passion of Dr. Arthur W. Combs, professor at the University of Northern Colorado. My colleague Scott Laidlaw heard Dr. Combs speak to this many times as he completed the coursework for his doctorate degree in education. And it stuck.

Decades later, this phrase is the driving force behind Scott’s dedication to transforming the way we, as a nation, teach middle school math. When our team at MidSchoolMath reviews the finer points of functionality for an online math game, outlines the theory of change for a new round of story-based math curriculums, or discusses if a new project idea might be viable, this is the element we come back to.

Are we answering questions before the students can even ask “Why”? Or are we offering students an opportunity to explore, to experiment, to wonder – and ask the questions that are most pressing for them?

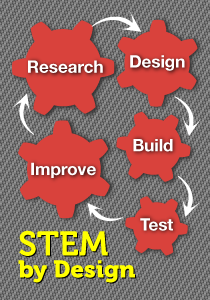

STEM makes room for the questions

After working with this concept for many months, I realized that this characteristic of STEM education – the creation of space where students can ask questions – is what attracted me to pursue STEM studies for myself, despite my initial intentions to pursue a career in public relations or public policy and the environment. It’s why I find myself – a student who struggled with math anxiety throughout junior high, high school and college – working for a math education organization today.

This is powerful. And this is happening every time a teacher uses a STEM lesson strategy they found on a site like this one; every time an instructor tasks students with a real-world STEM challenge and every time a student sits down in a maker workshop. The STEM (and STEAM) movements have been and will continue to be an exciting catalyst of transformation and inspiration for students and teachers alike.

But what about math?

Hands-on, exploration-focused STEM education has been thriving in corners and pockets of the K12 education system for decades now. And with the additional inspiration coming out of the maker movement, it’s picking up steam (pardon the pun) and becoming much more visible in the mainstream curriculum.

All of which is great — and (one would think) a cause for celebration by those of us who champion the “M” in STEM and are passionate to see more wondering and questioning going on in math and math-related classrooms.

But more often then not, we are finding, the excitement and inspiration of STEM is mostly happening in the science classroom, the technology lab, and in the outside-the-classroom educational programs. Math certainly plays an important role in the calculations, but it often feels to us like math is something of an afterthought — fulfilling the acronym — coming in right at the end.

Why aren’t we (the math lovers and champions) embracing the opportunity to teach math theory and concepts and practice calculations through STEM exploration in the math classroom on a more regular basis?

If we are to prove to students that math is truly important, and worth learning, shouldn’t we offer more opportunities to create a highly engaging space for asking and learning, within the formal structure dedicated for teaching math?

Let’s make math a STEM priority

We must make sure the math classroom offers clear opportunities to explore and experiment with core concepts of geometry, fractions, ratios, algebra and more, with students thinking about, asking questions about, and applying theories and concepts, rather than focusing on memorizing formulas or racing through calculations. There are many, many ways to do this, from pretend play and story-telling to manipulatives and online games. And, most certainly, through STEM explorations that put math front and center.

Let’s not always leave the M until last in STEM. Math teachers need to leverage STEM as they strive to promote the conceptual understanding called for in the Common Core. Let’s create cross-subject collaborations that create greater cohesion between the settings where STEM is already happening and the topics covered in math class. Let’s keep creating lots of space for exploration and not be hesitant to do it in the math classroom.

Within that space, math students will create more and better questions – and then, only then, will they begin to truly care about the answers.

Martha Riecks is director of outreach and communications for Imagine Education/MidSchoolMath, and serves as the Director for the MidSchoolMath National Conference (March 26-28, 2014 in Santa Fe), a gathering created for middle school math teachers who are striving to” stop the drop” in student engagement and performance in middle school math by transforming the subject through new innovations and classic pedagogies.