No-Holds-Barred New Teacher Advice

We suggested that Nancy Flanagan ask herself some questions – the kind that new teachers in the middle grades might ask.

Let’s dispense with the obvious, right off the bat.

If anyone takes a job as a middle school teacher, someone–or more likely, many people–will ask them: Are you nuts?

It’s not even close to a fair question. It’s a reaction to a moth-eaten set of myths:

- Hormone-addled young adolescents are impossible to teach.

- Middle school is where they send the loser teachers–those who lack subject/discipline depth, who enjoy cracking heads, who couldn’t make it at other levels.

- Research shows 13-year old brains aren’t receptive to important knowledge.

- It’s the worst period in a person’s life.

- Middle school is an academic holding pen that doesn’t count in a student’s permanent record.

- The most “effective” thing to do with middle grades is combine them with elementary grades (or any other pet grade configuration).

Children in America go through a uniquely individual process of growth and development. At any given point, not just the middle grades, they’re likely to hit speed bumps, experience periods where their ability to learn fluctuates, their interests shift, their relationship to the world changes, for better or worse. At all of these points, what happens in school matters–very much–in their overall intellectual advancement.

Here’s the takeaway: Stop stereotyping middle school teaching and–especially–middle school students.

Now about those questions I’d ask myself . . .

► How can I build trusting relationships with these students?

Ask questions. Share your own stories, occasionally. Prove you’re not going away — that you’re committed to their learning (which is different from being entertaining, cool or too buddy-buddy).

Be patient in this work. Middle-grades children are excellent at detecting insincerity, and they will keep pushing you to reveal cracks in your friendly demeanor. Trust begins with mutual regard and keeping lines of communication open — especially on days when the teaching-learning cycle breaks down. Practice tolerance. Have faith. Remember that relationships, like bones, are often stronger in places where cracks have had to heal.

► How can I set up a classroom environment that encourages my students to express themselves openly and genuinely respect others?

This is harder to do — and more important — than it may seem. From the physical layout of the room, to the handful of critical understandings and procedures you instill as part of your daily work together, thoughtful design for interaction and constant analysis of what’s working/not working are essential. They’re also wildly underestimated by those who equate “classroom management” with rules and consequences.

Your goal is to make your room a place where each person feels heard and valued. This is not something that can be accomplished immediately, nor does it have much to do with “decorating” the room or moving the furniture around. You can’t feng shui your classroom into a place where learning is facilitated. Sometimes, you don’t even have your own space.

A brief, illustrative story: Once, my middle school held a contest to see which homeroom could create the best door decorations for Christmas. The prize: donuts and cocoa for the winning class. The stated objective was building school spirit; administrators and office staff were judges. I had some personal reservations about the competition, but I wanted the kids to handle the question of what to do with this collaborative (and mandated) task.

In the end, they put butcher paper over the door, and scribbled their ideas on an improvised graffiti wall. There were sketches (including a Star of David), cartoons, and taped-on items — battered ribbon bows, broken toy parts, dead pine twigs. It was the talk of the building; students came to read The X-mas Wall and write their own thoughts. It was an interactive display until mid-January. Of course, the judges chose an elaborate, teacher-funded door with flashing lights and real evergreen boughs–but my students weren’t in it for the donuts.

My contribution? Provoking the discussion, and getting paper from the art supply closet, where students weren’t allowed. But it took a lot of restraint on my part. And an environment where students could kick ideas around.

► How can I deconstruct my assigned curriculum, highlighting and hammering home the things my students really need for high school, college and adulthood?

Most new teachers are given a set of content standards, goals and benchmarks — or, at the very least, textbooks and other required materials. That’s a good thing. Teaching well involves vastly more planning than most people realize, and that planning is incredibly complex. There are always key concepts that must be taught, skills and knowledge to measure. That’s the easy part. Getting advice from your colleagues is an essential launch strategy. Playing it safe is a good bet, at first.

But you didn’t become a teacher to follow someone else’s lesson plans. Ultimately, you became a teacher to teach kids what they need most — and that’s a matter of expertise and human judgment, not black-line masters, course outlines or even clever videos. Sooner rather than later, you must look at the prescribed curriculum and decide: Which of these things will my students need for the next test? Which will my students need for the next year? Which will they need for the rest of their lives?

Far too many teachers see instruction as a series of boxes to be filled, moving from chapter to chapter, lesson to unit, quiz to test. Their students may comply, but see little relevance. It’s the things that students need to be successful adult citizens — productive, happy, curious — that will generate your most engaging lessons. Think long-term.

► How can I embed real tasks and responsibilities into the assignments I give my students?

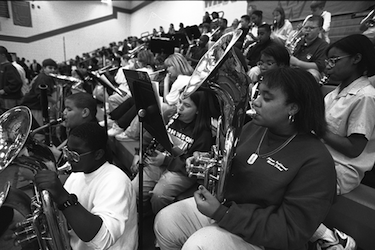

A truly excellent middle grades teacher will take seriously the work and opinions of his or her students. Seventh graders can write credible letters to the editor and mount impressive dramatic productions. They can solve real problems without following an algorithm. They can design structures, debate issues that matter to them, and craft poetry. They can compose songs, and sing them while accompanying themselves. They can hand off the ball to someone under the basket, and lead a campaign to get healthier food in the cafeteria.

Every time we give middle school students genuine leadership roles and real jobs, there is a possibility that they will fail. But too much hovering, scaffolding and doing something merely for a grade, rather than a tangible outcome, pushes middle grades kids to act more like children, just when they want most to try out their adult skills and options.

My best advice to you? Keep it real.

Nancy Flanagan (@nancyflanagan) spent 30 years teaching in a K12 music classroom in Hartland, Michigan, much of that time in the middle grades. She was named Michigan Teacher of the Year in 1993 and was an early successful candidate for National Board Certification. As a member of the Center for Teaching Quality’s national Teacher Leaders Network, she co-authored two major TeacherSolutions reports on teacher professionalism. Today, she’s an education writer and consultant focusing on teacher leadership. She writes the no-holds-barred blog Teacher in a Strange Land for Education Week Teacher and serves as a digital organizer for IDEA (Institute for Democratic Education in America).

Thank you, Nancy, for sharing key ideas to help early career and transitioning teachers get off to a more positive start to the school year.

Yes, thank you, Nancy, for sharing your insight & wisdom!