The #1 Close Reading Skill

This post is adapted from Sarah Tantillo’s forthcoming book, Literacy and the Common Core: Recipes for Action (Jossey-Bass, 2014). Sarah is also the author of The Literacy Cookbook (Jossey-Bass, 2012).

I’ve been reading a lot about “close reading” lately. Some people say you should re-read the text. Some say you should mark the text up with a pencil. Still others say you should ask a particular set of questions; unfortunately, I can’t remember what those questions are.

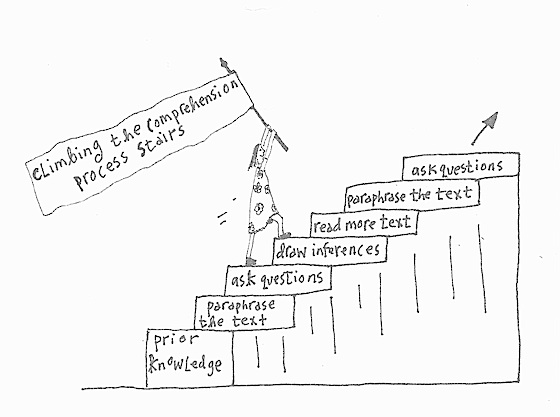

I’m not saying that any of these are bad strategies. I’m just saying they’re not the most important one. The most important skill you can teach your students is how to ask questions. To be effective at reading a text—any text: a story, a poem, a graph, a painting, an opera—you need to be able to ask good questions. As The Literacy Cookbook explains, questioning is an essential step in the comprehension process. Let’s review how it works:

This is why it’s such a problem when you can’t ask good questions: If you don’t ask a logical question, you won’t arrive at a logical inference. In fact, you will keep searching for the answer to the illogical question you raised, and when you don’t find it, you will probably become confused and frustrated.

Why students struggle with questions

Students struggle with asking questions for several key reasons. First, they typically have very little practice. Parents need to understand that when their children ask “Why?” incessantly, they are not trying to be obnoxious, they are simply trying to understand the world. So, as much as it might tax your patience, it’s really important not only to answer that question (over and over) but also to encourage your child to ask it…and others.

More effective teachers, instead of just talkingtalkingtalking, ask questions to engage students and check for understanding. Now, asking questions is necessary and helpful, but it’s not the same thing as modeling how to ask questions and giving students lots of practice in asking questions. So while the teachers who ask questions are more effective than the ones who don’t, they’re still not teaching the skill students need in order to be good readers.

Another big reason students don’t ask questions is because we live in a culture where there is a widespread misconception that “if you ask questions, you don’t understand, and therefore you must be stupid.” Students are not stupid; they get this. They don’t want to look stupid, so they don’t ask questions.

Flipping the script

So, we need to flip the script. We need to teach students the value of asking questions. We need to teach them that good readers ask questions constantly and that asking questions helps you figure things out and become smarter.

OK, so how do we get students to ask logical questions about texts? We can’t do it if we are always the ones asking the questions. So we need to train them to ask the questions. Questioning the text needs to become their habit.

The good news is: It isn’t complicated. I mean, it’s challenging (mainly because for most students it’s a new skill), but it’s not complicated. The tool you need is simple. It looks like this:

| QUESTION | INFERENCE | EVIDENCE & EXPLANATION (Include page number) |

Here is a model based on the first page of The Lightning Thief by Rick Riordan. I like this text because it is super-captivating and the vocabulary is not too challenging, so students don’t get stuck asking literal comprehension questions (“What does this mean?”) and can instead focus on inference questions.

| QUESTION | INFERENCE | EVIDENCE & EXPLANATION (Include page number) |

| Who/What is a “lightning thief”? Why/How would someone steal lightning? | It’s probably either the narrator or someone in conflict with the narrator. | BK (Background Knowledge): When a book title refers to a person, usually that person is either the protagonist or the antagonist. |

| How/Why does one “vaporize” another person? | It doesn’t sound good, but it does sound like the narrator has a sense of humor. | “Accidentally” vaporizing someone sounds like an extreme thing to do by accident, and it sounds a little funny. |

| What is a “half-blood”? Why didn’t the narrator want to be one? | A half-blood is probably half-human and half-something else. Maybe he doesn’t want to be one because he doesn’t feel comfortable being “different.” | BK (Background Knowledge): In the Harry Potter books, some characters are half-wizard, half-human, and there is a “half-blood prince.” Also, students often want to feel like they belong; they don’t want to stand out. |

| Why would someone’s parents lie about their child being a half-blood? | It sounds like being a half-blood is not normal and is somehow bad. | When the narrator advises, “Try to lead a normal life” (p. 1), it suggests that being a half-blood is not normal. Also, BK: parents sometimes lie to their children to protect them from hurtful information. |

| Why/How would someone kill a half-blood? | Probably some people hate half-bloods for not being “pure.” | BK: Throughout history, people have been discriminated against and killed for being different (e.g., Civil Rights, Holocaust). |

| What happened? Is this someone’s diary? | It sounds like something bad happened, and this is someone’s diary. | The narrator says, “If you’re reading this,” meaning this text and since it’s told in first-person, it could be a diary, and the line “I envy you for being able to believe that none of this ever happened” suggests that something definitely did happen (p. 1). |

| Who are “they”? Why will they come for you? What will they do? | I don’t know who “they” are, but they must not like half-bloods and must want to kill them. | Based on prior knowledge (such as the line “Most of the time, it gets you killed in painful, nasty ways”), it sounds like “they” are evil and will try to kill you if you are a half-blood (p. 1). |

| Why/How is Percy “troubled”? Why is he no longer at Yancy Academy? | I think he was kicked out for vaporizing his pre-Algebra teacher. | It says, “Until a few months ago, I was a boarding student at Yancy Academy,” meaning he’s not there anymore, and the chapter title could explain why he got kicked out (p. 1). |

Rick Riordan, The Lightning Thief (New York: Disney-Hyperion Books, 2005)

Here are some tips about this technique:

► Ask mostly “How?” and “Why?” questions because these lead most directly to inferences. When students ask other questions, see if they can reframe them into “How?” or “Why?” questions. For example, if someone asked, “What kinds of things do parents lie about?” I would see if the student could change it to “Why do parents lie?”

► Complete the organizer from left to ri ght. As you’re going through the lesson, try to generate inferences in response to questions immediately; don’t wait until students have brainstormed 20 questions before you ask for their inferences. We want them to see how questions lead directly to inferences. Also, if you ask all of the questions first then go back and try to figure out inferences after you’ve read the whole text, students will become very confused. The comprehension process demands that you try to draw inferences immediately when you ask a question.

► In the “Inferences” column, use words such as “maybe” and “probably” because these are inferences/arguments, not facts. When modeling, be sure to explain to students that we are using these words to signal a level of uncertainty and the need for evidence and explanation to support our ideas.

► Make sure students provide explanations, not just evidence. When students write, they often shovel evidence into paragraphs like coal into a furnace. Then they don’t explain it, and we can’t tell how the “evidence” supports their argument. Sometimes it’s our fault: I’ve seen teachers use acronyms for writing steps that did not include the word “explain.” You get what you ask for, so make sure to explain why students need to explain, then teach them how to do it and hold them accountable for doing it.

► Keep the questions neatly aligned in a “row” with their inferences and evidence/explanation. You might want to modify the organizer to give students well-spaced boxes to keep their work neat and easy to read (PS: It’s a table in a Word document; just insert rows). It’s also a good idea to give students a model with a row or two completed, to set up the “I Do, We Do, You Do” approach on the handout.

► It’s fine if some questions remain unanswered. In fact, it’s a great opportunity to point out that “probably 90 percent of the questions you ask about a text will eventually be answered if you keep reading.” That’s pretty cool, right? As a practical matter, students can put a circle in the margin next to unanswered questions and add check marks in the circles when they find the answers.

► It’s important to cite page numbers even if the sources all come from the same page because you will probably use this organizer at various points in the text, not just on Page One. While this activity can work well with the first page of any text—because that’s often when students have the most questions and because the goal is to stimulate their curiosity so they will want to read more—you should also use this approach when you want students to slow down and pay more attention to a particular section of the text. Later, when they sit down to write something about the text, they will want to know where to find the evidence that supports their ideas!

Download this article as a PDF

Sarah Tantillo is a literacy consultant who taught secondary school English and Humanities in both suburban and urban public schools for fourteen years, including seven years at the high-performing North Star Academy Charter School of Newark. She’s the author of The Literacy Cookbook and offers professional development help at her website of the same name.

Love this!!!

Amazing input. I’m going to give this a try. I am reading the Titan’s Curse as a read aloud. My 4th graders are captivated. Thank you for such a clear example.

Fabulous. Posted for my staff to read.

I appreciate the kind words. This organizer works with nonfiction, as well. One caveat: text selection matters, esp. when launching this approach. Pick something juicy! Save dry, heavily factual texts for students to practice SKIMMING (an often-overlooked skill also discussed in my next book and about which I will blog soon). Cheers, ST