The Revolution: Choosing Sides

A MiddleWeb Blog

by Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters

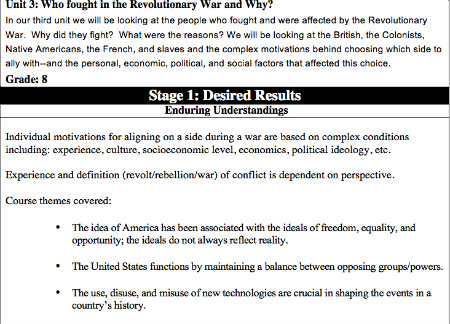

In California, both fifth and eighth grade cover the American Revolutionary War as standard content. We struggled the first year to convey this complex topic to the students. There was so much context necessary to understand the war, and we were determined to come at it from a different perspective than just a review of the important battles.

In that first year, Compton (CA) USD teacher Aaron Brock, our MiddleWeb co-blogger, and Jody planned a Revolutionary War unit around the perspectives of the different historical characters who experienced or participated in the war and their complicated motivations for choosing their side.

We were hoping that because, taken together, these real characters’ lives encapsulated the historical context for the Revolutionary War, the study of said characters would go a long way toward giving full context for the war.

Unfortunately, that’s not how it played out in the classroom.

More background was needed

It quickly became clear to us that we needed to provide the students with the explicit historical context for the Revolutionary War. In order to explore the perspectives and motivations of the historical figures, students needed to understand the world in which the Revolutionary War was fomented – a world very different than 21st century America.

To this end, we created a lesson that walks the students through some of the most important contextual events/ideas at the time — a brief tour of the “Causes of the Revolutionary War.” *

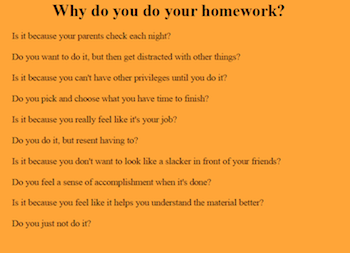

As an anticipatory set, we ask the students to reflect about the reasons why they do their homework. Homework and war are clearly not commensurate in importance or gravity, but we want them to reflect on the idea that just because an outcome is the same, our motivations leading to the outcome can vary.

Causes of the War

Causes of the War

We go through different causes for the war that we wrote in order to be as concise and clear as possible. For example, when we discuss taxes, we tell students:

As you already know, colonial powers have the ability to tax their colonies when they need money. Britain spent a lot of money in the French and Indian War in defense of the American colonies, and needed to levy (issue) taxes.

► Stamp Act: A tax on paper goods. After protest, this tax was repealed (undone).

► Townshend Act: A tax on tea, glass, paint, and paper. These were items the colonists imported from England. After protest, all but the tea tax was repealed. But the colonists wanted all of the taxes repealed, and when the tea tax remained, they held a protest known as the Boston Tea Party. A group of colonists, dressed up as Native Americans, threw an entire ship’s worth of tea into the Boston harbor out of protest.

► Intolerable Acts: King George was so angry about the Boston Tea Party, which he perceived as an act of rebellion, that he felt there needed to be a stronger British presence to keep order in the colonies. He instituted many harsh rules and taxes, which took away some of the liberties that the colonists had grown to expect. One of these rules was that colonial families had to quarter, or keep, British soldiers in their homes.

1. Who do you think were most affected by the taxes? Explain your answer.

Choosing Sides

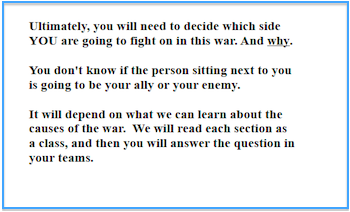

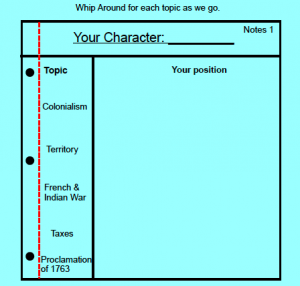

We also look at the French & Indian War, colonialism, territory, etc. Students then take on the persona of a group of people at the time: Loyalists, Patriots (we talk about the significance of the titles), Native Americans, and Slaves.

Students then decide what their perspective would be on each of these issues that caused the Revolutionary War, resulting ultimately in the students deciding which side they are going to be on. Patriots, clearly, choose the Patriot side, some Loyalists end up divided, Native Americans often join the British, and some of the Slaves, after hearing about Dunmore’s Proclamation, often join the British as well.

This approach ended up being a combination simulation/didactic lesson that has worked very well the past few years. Providing some background and perspective on the front end really helps the students when they do begin to study the historical characters in depth. Becoming more firmly rooted in historical context increases their understanding of the complex motivations of Joseph Brandt, Phillis Wheatley, John Adams, Colonel Ty, Abigail Adams, and many others who found themselves choosing sides in our nation’s founding struggle.

These teachers have already revised this unit based upon prior experiences. This is good practice. There remain at least two areas of concern — historical accuracy and use of essential questions.

The information regarding the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts (pl.) and the Intolerable Acts is inaccurate (see Morgan and Morgan, “The Stamp Act Crisis”; Davidson, et al. “Nation of Nations”; Bailey and Kennedy, “The American Pageant”).

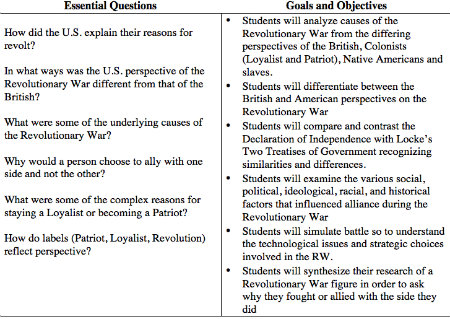

The reference to essential questions in the unit does not conform to the discussion in “Understanding by Design” (Wiggins and McTighe) concerning “essential” versus “unit” questions. The questions used are too specific and numerous for “essential” questions.

Thank you so much for your comment. We will definitely look at the historical resources you mentioned and we so appreciate feedback so we can continue honing our unit. Agreed, these may be more unit questions than essential questions. While we were trained in UbD, we tend to be a little loose with EQs especially- should have revised the label.

Some revisions: What can the labels those on each side use to describe themselves and the other side in battle tell about the conflict? (Language needs to be perfected there, but that would clearly be more of an EQ)

William, thank you again for your comments. We searched online for a summary of the books you mentioned but had no success. We will track them down and have a look.

No question, the little summaries we wrote are simplifications; this was a pedagogical choice as the details were not part of our main objective in this activity. If we had more teaching time, we would have included more information – even bringing in differing perspectives on the same historical event (something we do in our course of study to make students aware that history is created by scholars). In this instance, the information we did choose to include in this lesson is accurate, though cursory.

Thanks for describing your unit. Are you familiar with the game ‘For Crown or Colony?’ http://www.mission-us.org/

I have had great success using it with my 7th grade students here in Boston. It deals very directly with the question of how individuals determined which side to support, which sounds like you address.

I would love to share more ideas and swap curriculum.

Hope you are well.

Jared

Hi Jared! Great to see you here. I have actually been playing around with that game over the past few days. I would love to hear how you incorporate it into your curriculum –yes, let’s swap for sure.