Scaffolding the History Essay

A MiddleWeb Blog

“Was the Revolutionary War justified?”

Often a classroom debate over a question like the one above will convince a teacher that they have succeeded in promoting critical analysis in their classroom. With the teacher acting as referee and coach, students raise salient points and support them with evidence from a variety of texts.

Afterward, the instructor will feel that getting students to commit their ideas to paper in the form of an organized essay is merely a formality. Instead, we educators are reminded that “pride cometh before the fall.”

Writing a thesis-driven essay using evidence from a variety of texts is a challenge for most middle school students, regardless of their background. The problem may be more acute at schools like my own, where most of the students read significantly below grade level, but it is only a matter of degree.

Some of what I have discovered works for my students may be redundant for those whose students do not struggle with reading or suffer from a dearth of background knowledge, but any student who struggles with writing an evaluative piece can benefit from a structured writing assignment.

Narrow the Focus

Posed in a college seminar, a question about the ultimate causes of the Civil War could spark a two-hour debate pitting the concept of popular sovereignty against ideas about universal human rights. Some might eschew this false dichotomy altogether to propose that it was ultimately the attempt of each branch of the federal government to assert its dominance over the other two that eventually led to impasse and dissolution.

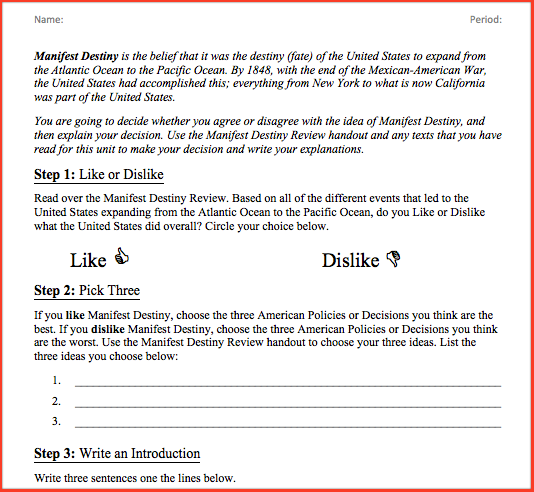

As a history student, these debates are invigorating. As a middle level history teacher, such thinking can be counter-productive. We must remember that most of our students often have a limited store of discrete knowledge about the content being evaluated. Additionally, writing using textual evidence is usually new to middle school students as well. Asking students to assimilate new knowledge and then immediately reassemble it into an unfamiliar format is already daunting. We can make the essay itself less daunting by providing structured choices for the students.

DOWNLOADS:

• Manifest Destiny Essay Outline

• Manifest Destiny – Monroe Doctrine

• Manifest Destiny – Texas & Mexico

For my students, this choice is always binary. Every unit is centered on an essential question for which I provide a simple dichotomy:

- “Who were the good guys during the American Revolution?” (British/American Colonists)

- “Why was the United States Constitution written?” (To control us/To promote justice)

- “How should Americans feel about Manifest Destiny?” (Like/Dislike)

As college-educated adults, we understand these questions have more complex answers. However, my students struggle with reading comprehension, so locating evidence alone presents a challenge. When I provide the possible viewpoints up front, students can focus their energy looking for specific evidence to support one case or another. Even if they pick their point of view at random, they are still learning to seek evidence to support a thesis statement.

A few of these students will even change their minds if they feel like they cannot find sufficient evidence to support their original claim. Students learn to view historical texts as bodies of evidence supporting a particular point of view, rather than factual narratives to be taken at face value. Changing the dominant student view of history as a litany of irrefutable facts is an essential step in promoting evaluative skills in students.

Teach the Controversy

To successfully introduce the idea that history is a series of arguments supported by evidence, students must be able to recognize and locate evidence on their own. Because the skill is new to many students, I make certain that the available evidence is in discrete, easy to find chunks.

When I write texts for my students (download two examples above: Monroe Doctrine and US/Mexico), I make a point of including an equal amount of specific evidence to support both of the possible views. If students read texts I have not written, I use excerpts from more than one author.

The purpose of this scaffolding is not to stultify the creative or analytical potential of my students. Limiting the scope of a historical argument allows students to think deeply about why they support a particular answer to the essential question.

Requiring students to take a side forces them to carefully evaluate their reactions to texts and lectures throughout the unit. If only two choices are available, students who have failed to thoroughly consider their opinions will find obvious inconsistencies in their arguments. This reinforces the idea that historical narratives should be actively interpreted rather than passively accepted.

Different Strokes

There is always at least one student who looks at the available choices and rejects them both. He or she will express a more nuanced opinion about the historical material being considered and support this idea with a sophisticated understanding of the evidence. What is the best course of action when confronted with this student? Do a jig. Give the student a high five. Congratulate the parents for doing such a fine job. Then, with careful guidance, allow the student to construct her or his own thesis.

If the student gets bogged down, encourage them to take on a simplified thesis, and then help them build toward complexity from there. Ideally, more than one student is prepared to write their own thesis after being exposed to several structured writing assignments. The idea is not to leave any student completely behind as each comes to their own conclusions about the subjects under investigation.

Even those students who never quite make the leap to creating their own theses in your class will be more analytical when reading and thinking about history. The goal is to get the students moving in the direction of evaluation and allow them to continue in that direction at their own pace.

Thanks for such a great blog on a difficult topic for any teacher. Teachers tend to shy away from this type of process because they just can’t get organized in their planning for it. You have provided a practical framework for use with any topic.

I have included a link to your blog on my Project Share portfolio.

I’m wondering if you might explain your use of the term thesis (a descriptive beginning for informational writing) when students are being asked to make an argument with claims? I know that with my peers, this is an area of inquiry, and I’d like your point of view. Thank you!

Thesis can be defined as a proposition to be proved or defended with evidence (I am paraphrasing Merriam-Webster). I usually do not introduce my students to the word itself until much later in the year. If they are already defending theses in writing, it is relatively easy to introduce the term. Trying to introduce the concept of thesis with a definition too early can often be counterproductive, as students will focus on the new term rather than the development of the new skill.

In the worksheet you mention that completing it earns a C-. How do they earn full credit? What more has to be done?

Sorry, the copy used for this post is an older version of this assignment that did not explain everything. Students who wish to receive a higher grade on the essay give me the organizer a week before the final due date; I give them notes and make edits based on what they need (I prioritize structure and argument over spelling and grammar, though I will edit for the latter for my more advanced students). Students then take the edited organizer and rewrite the essay on blank paper. The second essay can earn the student more than a C-, assuming they actually incorporated the edits.

I allow students to turn in the organizer for a C- because for many of them that is all they can reasonably complete in two weeks (with other classwork, of course). Sustained writing is a long way off for many of my students, so this gives them the practice they need, teaches them some structure, and does not appear as daunting as a “real” essay. Of course, they are actually writing a thesis-driven essay, just with a great deal of support.

Essentially, I allow students to self-differentiate on this assignment. Those who feel they can manage it will get feedback and rewrite. A few students are even willing to go through more than one draft.

I am happy to share some of my more recent versions of this assignment, if you would like to see them. They are a little clearer. Contact me if you are interested: brockrms@gmail.com

Here are two of Aaron’s more recent versions. Thanks for the interest!

— John at MiddleWeb

Argument Essay 2: The American Revolution

Argument Essay 3: The United States Constitution

Thanks, Aaron. Do you know about the DBQ project?

Aaron — thanks for the scaffolding tips! As a high school history teacher, I push my students to write with thesis, evidence, and explanations of how/why their evidence helps prove their thesis. These are great springboards to facilitate differentiation for me. :-D Your most successful kids would be very well prepared for AP after completing these types of assignments.