Writing Conferences: Praise & Focus Critical

My favorite part of any workshop is conferencing with students one on one. I love listening to their explanations, watching them think, and even seeing a new idea inspire their minds— it flashes across their faces and raises their eyebrows in a moment of enthusiasm.

Conferencing is my chance to show students my interest in each of their papers, and in each of them; it’s an opportunity to connect with them on a level that can’t be achieved during whole-group instruction.

What adolescent doesn’t want genuine, encouraging interest from another person? Our knowledge of their papers and our desire to help them strengthen their ideas make them feel worthy and important. Students quickly realize they have an audience who cares. They learn that writing—their writing—matters.

During a conference, I will discuss anything at all that will help further the success of a piece of writing. At any given moment, I act as detective, coach, instructor, psychiatrist, audience, archaeologist, cheerleader, or disciplinarian. The two main pillars of any conference, though, are praise and the focus on meaning.

The Importance of Praise

I always begin a conference with a positive comment. Sometimes this is easy; sometimes I have to search. The comment cannot be faked though, not only because adolescents sense duplicity and loathe it, but more important, because I also want to genuinely encourage them. So I search.

I’m not afraid to be silent at first, either reading what they have written or shuffling through drafts and notes. Students are used to watching me think in front of them. And without fail, something, somewhere, exists for me to praise. Even in the worst-case scenario, when a student is angrily sitting in front of a single blank sheet of paper in total defiance, I can say something such as, “You wrote a wonderful ode a couple weeks ago; you’re good at describing. I know you are perfectly capable of doing this assignment as well.”

I don’t coddle students—they must always know that they are expected to work hard and thoughtfully—but honest, appropriate praise can often go a long way in rejuvenating a stuck student, perking up a lazy student, or reengaging a distracted student who is on the verge of misbehaving. With most papers, I can easily find something—a rich prewrite, a well-written intro, an original simile, a well-organized paragraph, something—that merits sincere appreciation.

And the brief time it takes to praise is worth it. In addition to allowing me to connect with students, praise pushes them even further into the writing: when they know that parts of their piece succeed, they are motivated to revise the parts that lag.

The Focus on Meaning

When looking at a piece for the first time, I check to see if it’s substantial enough to deal with as a draft. If not, I must help that student build it up from the inside out. If the draft seems sufficient, then I generally direct student revision from the outside in: first organization; then details, examples and language; and then grammar.

That said, I do not necessarily wait until the final conference to talk about grammar. Often it will come up once the process of revising the details, organization, tone, and such is underway. Once I have students confidently revising one aspect of their draft, I will mention a pattern of grammatical mistakes that needs attention. Although meaning trumps grammar in the initial conferences, grammar is not insignificant; it is merely secondary.

Overall, I enjoy helping students master the conventions of our language. It empowers them. With grammar, I try to take the tone of a teammate rather than a teacher, acknowledging when the rules of grammar are difficult or even illogical, while communicating my belief in students’ ability to grasp them.

In Part 2 of her article on conferencing with student writers, teacher-author Marilyn Pryle tells how she manages multiple conferences with each student during a class period. The key: give students small manageable tasks they can do on their own. She offers some examples of such tasks and tips for orchestrating the process.

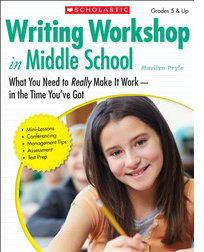

Marilyn Pryle is a middle grades language arts teacher who lives in Pennsylvania. She is the author of several professional books from Scholastic. This article is adapted from Marilyn’s latest book, Writing Workshop in Middle School (2013), reviewed here. Follow her on Twitter @mpryle.