Teaching History Students to Recognize Bias

by Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters

by Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters

“There are two sides to every story.” How often, especially as teachers, have we heard that? When our students come to us with their problems, we try to hear all sides and do our best to help the students solve their issues.

Yet, we don’t often allow our students to see all the different sides of historical stories. (And, of course, there are usually more than two!)

Perhaps this is because of time constraints or concern about pushback from those who might question our curricular choices. Or maybe it’s just our anxiety that bringing in this level of complexity will muddy already challenging concepts. Yet, aren’t we doing our students a disservice if we don’t allow for multiple perspectives in the history classroom?

History is complex, and the story that gets told depends on who is writing the history. It’s never really too early to introduce that concept. Most students understand the idea of two or more sides to a story, even if they believe that “their” side is inherently right.

Objectivity may be impossible

Each and every step of historiography (we talked about introducing the concept of historiography to students in a previous post) is fraught with choice and interpretation. It’s the nature of scholarship. This results in dominant narratives, varied accounts of the same historical event, and different interpretations of peoples’/events’ historical significance.

Given this ever-present ambiguity, students must be explicitly taught how to try to discern a particular historian’s or publishing house’s bias. That way, they can be more analytical consumers of historical information.

In our classrooms, we want the students to be able to separate the evidence from the analysis and decide for themselves what may, or may not, have happened. They should be able to determine on their own what might have been important, and what may be exaggerated or skewed in the account they read.

Our teaching strategy

How do we teach this challenging skill? Well, since we teach eighth grade, the students are in a good place to do this kind of work. However, we feel that both of the main tools we use can be adjusted for younger students fourth grade and up.

► The first thing we do is talk about bias itself. In the older grades we talk about the idea starting with two interpretations of history that often challenge mainstream views: the documentary America, the Story of Us; and an excerpt from Howard Zinn’s A Young People’s History of the United States. We model with the students how to analyze what the authors included, left out, and the word choice–especially adjectives–that the authors use to make his or her point.

► Then we identify what that point is. Is the author trying to convince the reader of something? These two sources definitely are, which is why starting with their work–two sources that present differing views of the American historical narrative–is demonstrative of this concept.

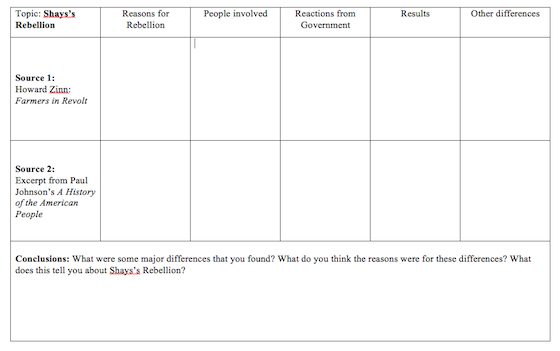

► Then we use a tool called an I-Chart (Inquiry-Chart) and modify its purpose slightly so that its main goal is to compare two different narratives about the same event:

This kind of graphic organizer could be used with any grade level. For example, students in fourth grade could look at two different narratives about Native Americans, one from a contemporary source and one from the 1950’s, or a primary source document vs. a secondary source document about a particular event in their state.

This side-by-side comparison opens up the idea for students that history is not one linear narrative and that “what happened” is not necessarily set in stone. Also, the I-Chart does not need to be limited to the comparison of only two sources. Depending on the developmental level of your students and their facility with this skill, you can compare as many sources as you feel would be appropriate given the subject matter.

The I-Chart requires critical thinking and analysis, especially when it comes time to discuss the findings. The I-Chart can’t stand alone. Students need to draw conclusions from their findings, both in teams and with the teacher, so that they can help parse out what the findings mean. And by meaning, we refer both to what it means for their understanding of the particular event and for their study of history generally.

History bias in the Internet age

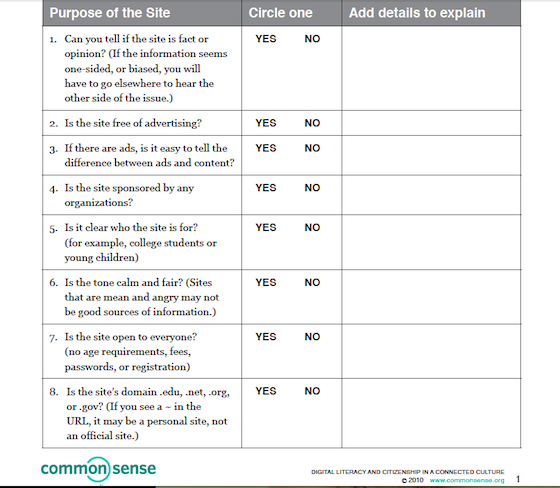

CommonSense Media has a great tool for 6-8 grades – one that we believe could be teacher-modified for 4th and 5th grades – called “Test Before You Trust.” It is a checklist to help students evaluate the bias of websites: who pays for the source, what advertisements are being promoted on the site, when it was last updated, what other sources are referenced by the site, and URL analysis, to name just some of the criteria. Then, with teacher and peer support, students discuss what effect the criteria examined by the tool might have on the bias of the site and how that can help us identify the author’s perspective on the historical event.

Students become more discerning consumers

How do you teach potential bias in your class?

This is an excellent ‘today’ or ‘until’ strategy for understanding history and historical perspectives. Until texts contain less historical biases, we give students the tools to navigate history intelligently. Teaching students to ask questions and outlining the types of questions to ask helps them discern reliability from skewed accountings mindful of subjective and rarely objective telling of facts related to people, places and events.

A shocking way to talk about bias is Stockholm Syndrome. Using YouTube video “ART Explains” I introduced my advanced middle school research class to the idea that history, even from a primary source, can be grossly biased. This leads to discussion of the revisionist history that slavery “wasn’t so bad because a lot of slaves fought for the South.” It’s an extreme example but it helps break the barrier that primary sources are infallible. I also gathered text books from the 1950s and we look at the treatment of Manifest Destiny. How Natives are treated in the books leads to some interesting discussions about racial stereotypes and the power of names (like savages, redskins) and then look at Pocahontas as Disney portrays First Nations. The correction to bias can also be biased. The goal of unbiased sources is obviously illusionary but helping students have open eyes is good start.