The Homeroom Is a Home

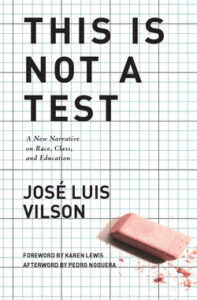

A visit to José Vilson’s website and blog will be revealing. This story about how a homeroom became a home is excerpted from his book This Is Not a Test: A New Narrative on Race, Class and Education. © 2012 José Luis Vilson. Used with permission.

By José Vilson

Seventh graders are at the bottom of the theoretical behavior parabola, based on some informal surveys I’ve taken with dozens of teachers (and non-educators) across the country. Upon telling them I teach 7th grade, many of them cringe, sigh, or just pat me on the back and wish me well. My naïveté got the best of me my first year. A pleasant group of 14 students, all nice and quiet and still, nothing like I expected my first day to be.

Day 2 came the rush. After 14 kids took their seats in the first few minutes, a lady walked in with about 16 children, loud and clamoring for lockers while getting their registration cards changed. I stood there waiting for the process to finish, observing a whole period of math gone for no reason. The administrators collapsed two 7th grade classes into one; 14 students became the congress of 30 known as 7H3. Of the three classes on this floor (7H1, 7H2, 7H3), this group was hand-engineered to run me through the rigors of teaching in an urban setting.

I was also assigned two high-level classes, one in the 8th grade (8A4), and one in the 7th grade (7A4). My advanced classes had better levels of student attendance, high levels of parent engagement, and uncanny levels of idiot savants. Only one of my students in those classes achieved the pinnacle of my tough grading policy. For me, 100% isn’t a gift; it’s a hard-earned grade, and I’ve only given this grade out to three people in my entire life. Pury from 7A4, who thought I would settle for her cute handwriting when her math wasn’t on point, was the first to earn a 100. Poor her.

7H3, despite their lack of academic thoroughness, had character. And characters. The loud and secretly nerdy group of Sonya and Salome, who I semi-adopted as my school daughter. The mellow cool of Dalido, Felix, and Rafael H. The young maturity of Bianca, Scarlett, and Josh. The dedication and commitment of Yuleisi, Christina, and JP. The giggly gum-chewers Destiny, Jennifer C. and “just L”. The extra-quiet Thannya with the extra talkative Kelly, and the radiant smilers who frequently came late, Ashley and Amber. The mischievous Jonathan O, the excitable Jonathan P, the beanstalk Jonathan S. And there was the calamitous Alex, whose job it was to make my job that much harder; the introvert Christopher, who just needed a pat on the back every so often; the quizzical Mahaish who always had a round of intelligent questions about everything we did, and Shanaya and Whitney, who snickered their way through every conversation.

They made it really hard to present myself as detached, but I tried really hard to stay as objective and measured with them as possible. I didn’t smile once until December (more on that later). I made them work mightily on almost everything, and chased them down through their English, science and social studies classes. I found out the talent classes they were assigned to, and if I saw them in the hallway, I’d escort them back to where they belonged. I was brutally honest to all of their parents from the first minute I called home.

My co-English teacher had exactly the opposite relationship with them. He rubbed a lot of people the wrong way, with his insistence on his perceived expertise in English-specific pedagogy. What hurt him most, though, was his hatred for the kids. He never had to say it. The students became so aware and in tune with that hate, they would run, scream, and shout to get into my room. In a raised voice, I’d simply look at all of them and say, “WHAT is GOING ON HERE?! Now, you all step back out of the classroom, quietly line up, and try that again.” Later on, they’d try to explain it to me, but I’d already heard the commotion. My wall grumbled from the energies the other classroom gave off.

At some point, a situation occurred between the English teacher and the class that resulted in Sonya, the unofficial spokesgirl for 7H3, bursting out of his room, shaking and in tears. Then the other students ran out, yelling their disdain for this guy, and eventually found their way to my room. One of my coordinators stepped in and asked me to look after Sonya while we resolved the situation. That moment pulled me out of Mr. Vilson mode for the day; I wasn’t taught how to handle these types of situations. In that building, she only trusted me and she wanted someone to listen. It’s a moment that I keep nearby, like a well-worn bookmark, so I can remember my place in this particular story. She called for me.

The horror stories of men getting into trouble for showing any sort of care for a young student made me pensive to cross my professional (read: cold) barrier to help her out. I sat next to her in front of the coordinator’s office in the shorter hallway while she cried her eyes out. She kept saying, “I don’t know why, I don’t know why …” I just sat there. When she exhausted herself, she put her head on my shoulder. I put my arm around her and let her cry as she long as she wanted.

Twenty minutes passed.

“I think I want to go back to class.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah. I think I’m done.”

“Alright. Cool.”

“Thank you.”

We walked back to her class. After dropping her off, I sat there in my room and let the walls vibrate, the ring in my ears nothing more than the quiet that occupied the big room.

Without trying to sound too dramatic about it, that was the day I discovered what people meant when they tell you teaching is a calling.

The times I felt I let them down. One time, I just decided to write all the notes on the board when they totally tuned me out. I didn’t teach or anything. I just sat there and didn’t stop them from doing whatever. A couple of the kids took notes, but the majority of them did exactly what they wanted. They went to their lockers, chatted with their friends, doodled in their notebooks, and didn’t mind just doing as they pleased. It was a huge failure in classroom management. But even more it was a disappointment, a breach of what I thought was a trust bond between that group and me.

After the class was over, I sat there in utter disgust at what just happened, rethinking this teaching business. What the hell was I doing? Did I really want to invest this much of myself on behalf of kids who totally disregarded me on a whim? Did I just need to quit and prove my doubters right?

But the pity party was short. This isn’t how it’s going to end.

That afternoon during homeroom, I sat them all down, their heads hanging and silent, knowing they were going to get the business. Then I had them all stand behind their raised chairs, and I gave them my version of the story you’ve read up to this point. They were astonished and ashamed. I lined them up, as we were wont to do, and dismissed them from the stairs. I looked away from them. I walked down the hallway, past my other classes. I ran into my AP and coach’s office.

I broke down.

Mrs. King (the coordinator for the floor) and Ms. Michel (the math coach) looked on as this young, usually composed gentleman told them the source of this emotional outburst. Then they did their best to make sure another math teacher didn’t bite the dust. I won’t share everything they said, but at the time, their words meant everything. I took the 1 Train to one of my graduate classes, ready to spill my guts about the terrible day I’d just had. My friend Indira, who I was still taking classes with, said it was about time. Most of my fellow Teaching Fellows said they’d had their breakdowns back in November. (One, in fact, had had hers right in front of me.)

Mentally drained, I had a hard time concentrating in my night classes. I wanted to apologize to my professors from throughout my college career. But I never felt inclined to make excuses for my own failures. After getting home at 8:30 pm, I said nothing to my mom about the day I had, only that I was tired and not particularly hungry. But I was. I was hungry for another day to make it up. I didn’t want a mental health break.

I came back the next day, renewed. I’d needed to be pushed to my limits — to find out where and what they were. Reminiscing on that, my UFT chapter leader at the time said in his burly gruff, “Vilson, you’re doing a yeoman’s job.” “Huh?” “A yeoman’s job.” “What?”

“You’re doing a HELLUVA job, Vilson!”

People in my position (along with researchers and experts) like to enforce middle-class values on non-middle class students who already come with a set of values that work for them. We’re well-meaning but we’re off track. We just need to work with what kids bring and use their values to our advantage. My homeroom doesn’t always care to behave well. They’re going to interrupt you, yell at you, curse at you, disrespect you. They’re not always going to walk in formation for you, or do all your homework, or speak in The King’s English. They’re not often going to love your lectures when you speak firmly to them. If your response as an adult is to highlight how much more perfect your class or culture is compared to theirs, then you really need a warm cup of empathy builder.

First round’s on me.

The kids of 7H3 ended the seventh grade knowing that the next year would begin with new school dynamics. They’d pushed every other core teacher to the brink of retirement or off the deep end by the last day of May. In the process, they’d developed forms of advocating for themselves like petitioning, letter writing, and telling parents to call the school whenever they had issues as a collective. I wasn’t sure about the source of their activist spirit, but I certainly had to respect it. Looking back, I think they were the first to teach me that homeroom classes often become a reflection of deeper truths about teachers — things we don’t necessarily reveal openly to them about ourselves.

Not everyone invests themselves into any set of children the way I learned to do that first year. But when I did, the homeroom became a home. For all of us.

His book This Is Not a Test: A New Narrative on Race, Class and Education is published by Haymarket Press (2012).

José is a National Board Certified Teacher and a Math for America Master Teacher. He currently serves on the board of directors for the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards and PowerMyLearning. He’s also a committed writer, activist, web designer, and father. He is the co-founder and executive director of EduColor, an organization dedicated to race and social justice issues in education. [Updated April 2024]

3 Responses

[…] For more, read here and comment there! […]

[…] This year, however, the students actually expressed that sentiment. I don’t have a homeroom (see my new excerpt about homerooms here), but I connected with this class so much. Here’s to a graduation, not just for them, but for […]

[…] Read about middle grades math teacher and coach Jose Vilson's journey…"Not everyone invests themselves into any set of children the way I learned to do that first year. But when I did, the homeroom became a home. For all of us." […]