Seven Simple Steps to Better Student Writing

This post is adapted from Sarah Tantillo’s book, The Literacy Cookbook (Jossey-Bass, 2012). Her second book, Literacy and the Common Core: Recipes for Action (Jossey-Bass), was published in 2014.

Some of my favorite foods are not difficult to prepare: grilled salmon, scrambled eggs on toast, chocolate milkshakes (smile). Good writing instruction doesn’t have to be complicated, either. No matter what genre you’re teaching (whether it’s a paragraph, a timed essay, or a full-blown research paper), I recommend the following seven basic steps:

2. Provide an excellent model and preview the scoring rubric, then use the rubric to critique the model, annotating it as you go. Keep a running list of the compositional risks or techniques that make the model successful—in other words, what works. For example, “use of strong vocabulary” and “effective transitions leading to smooth flow” will probably appear on most lists.

3. Invite students to critique models of varying quality so they can see the characteristics of effective and ineffective writing. Evaluating different samples will help them become comfortable with the rubric and your expectations for the assignment. It will also train them to be more self-critical when revising their own writing.

4. Explain why pre-writing is so important and hold students accountable for using pre-writing strategies. Particularly on timed essays, students tend to skip pre-writing because they believe it’s better to write for the entire allotted time. However, what often happens to students who don’t plan or outline their ideas is that they write frantically for ten minutes and then, like a sprinter who suddenly runs into a wall, they abruptly run out of things to say. (I like to demonstrate this with the nearest wall because it gets their attention). Then they spend the next 20 minutes in agony.

Our job is to teach them how to avoid hitting that wall. Along with teaching them the needed strategies, we must hold them accountable for using them. Grades signal what we value, and students will take pre-writing more seriously if you assign a grade to it.

5. Teach pre-writing strategies. For most writing assignments, the biggest challenge is generating an appropriate topic and argument/message. One problem is that students often don’t know the difference between argument and evidence, so we must teach this directly, as I’ve blogged here and here. Students also need to know the goals of the task, which graphic organizers to use and why, and, if it’s a timed task, how much time to spend on pre-writing. Model every step of the pre-writing process repeatedly and walk students through plenty of guided practice before giving them independent practice.

NOTE: Some teachers make the mistake of skimping on the “I do” and “We do” phases of the lesson, thinking that they will save some time. They won’t. Students who haven’t seen enough modeling tend to struggle with their independent work. Then you have to go back and re-teach. So it’s better to take the time up front and set students up for success.

6. Give timely feedback on the actual writing. If you’re teaching the writing process and have the opportunity to support students along the way, you should read their introductions and make sure they’re on the right track before continuing. It takes less than a minute to determine if a student has drafted a viable thesis, but there is no telling how long it takes to undo his frustration if he has spent hours writing a whole essay, only to be told that the thesis makes no sense. With very brief conferences, you can redirect students toward more productive lines of thinking.

If students are working on a timed essay, it’s best to grade the whole thing as soon as it is done and give students a chance to revise it based on your feedback. The lessons they learn from improving that essay will prepare them to do a better job on the next one. And if they can’t figure out how to fix this one, how can we expect them to do better on the next one?

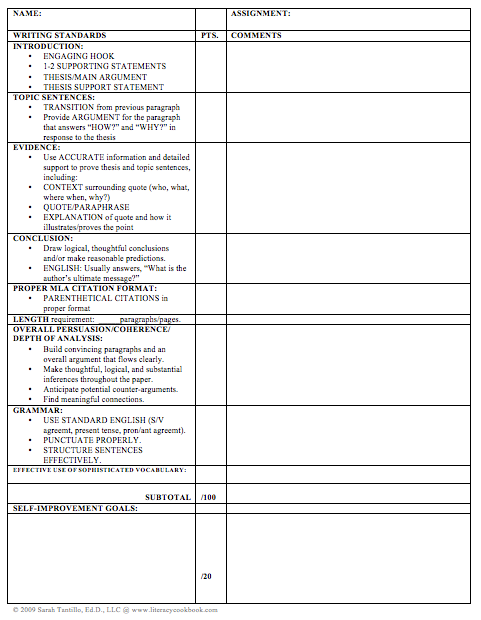

7. Last but not least, require students to reflect on their strengths and weaknesses as a writer. One way to support this self-reflection is to provide students with feedback and hold them accountable for following up on it. Below is an Essay Writing Rubric that includes a separate grade for “Self-Improvement Goals.” (This Essay Writing Rubric can also be found at my Literacy Cookbook website at the “Writing Rubrics” page.

Sarah Tantillo is a literacy consultant who taught secondary school English and Humanities in both suburban and urban public schools for 14 years, including seven years at the high-performing North Star Academy Charter School of Newark.