The 5 Rules of Student Engagement

Long before the oft-cited pandemic impact on student engagement, internationally recognized author and teaching coach Barbara Blackburn was sharing her truth about disengaged students. Her five fundamentals are still spot-on. (Updated June 2024)

by Barbara R. Blackburn

What exactly is student engagement? I recently read a comment from a teacher on an Internet discussion board. He said that his students seemed to be bored, and after talking with them, he realized that they were tired of just sitting and listening. He said they wanted to be more involved in their learning.

I was excited to read further. But not for long. The teacher said he decided to “change how I teach, so now I make sure I do one activity each month with my class.” How sad. That means 19 days each month spent in class with no activities to break the monotony of lecture-driven instruction.

Unfortunately, that describes many classrooms today.

A history of mediocre teaching

Don’t misunderstand me. There is a place in teaching and learning for lectures and explanations and teacher-led discussions. But somehow, many teachers fall into the trap of believing that lecturing at or explaining to students is all it takes for them to learn something.

Perhaps it comes from our own experiences. Whether we’re 30 or 60, quite a few of our teachers taught that way; it’s what we saw most of the time. But how many of those teachers were outstanding or inspiring educators? Not many. I had several great teachers, and none of them taught like that.

Here’s something else I remember: The older I got, the more I was talked at.

Where did that come from—the idea that as children grow up, they should be less involved in their own learning? It’s remarkable how this mistaken notion – utterly disproven by research – continues to survive and thrive.

The real facts about engagement

Let’s be clear on some basic points:

- Although students can be engaged in reading, reading the textbook or the worksheet and answering questions is not necessarily engaging.

- Although students can be engaged in listening, most of what happens during a lecture isn’t engagement.

- Although students working together in small groups can be engaging, students placed in groups to read silently and answer a question aren’t.

- Activities in groups where one or two students do the work isn’t engagement either. Small groups don’t guarantee engagement just like large groups don’t automatically mean disengagement.

So what IS engagement?

What does it mean to be engaged in learning? In brief, it really boils down to what degree students are involved in and participating in the learning process. So, if I’m actively listening to a discussion, possibly writing down things to help me remember key points, I’m engaged.

But if I’m really thinking about the latest video game and I’m nodding so you think I’m paying attention, then I’m not. It is that simple. Of course, the complexity comes in actually activating students. I’ve learned there are five rules for student engagement.

1. Make it fun, and learning happens.

2. Build routines, and everyone knows what to expect.

3. Keep students involved, and they stay out of trouble.

4. Make it real, and students are interested.

5. Work together, and everyone accomplishes more.

Rule One: Make It Fun, and Learning Happens

How much fun happens during your class? Think of it this way: If you had a choice, would you want to be doing the things you ask students to do? One of the easiest ways to make learning fun is to turn whatever you a doing into a game. I’ve been in classrooms that use adapted versions of Jeopardy, Bingo, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire (complete with lifelines), Wheel of Fortune, Concentration, and Trivial Pursuit.

Chad Maguire uses a numeration scavenger hunt, during which students must find 50 real-world uses of math. He writes:

“The students are excited to do this project, and it also opens the awareness that math is not just a subject in school.” It doesn’t take much to turn something into a game. Add some points and a little competition (either group or individual) and voila!”

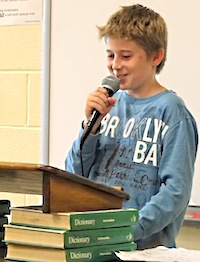

Erin Owens uses a popular television show to inspire her students:

After the “glamour” wears off, they begin to realize that they are showcasing their work each time they “step up to the microphone.” I began to see a major change in their motivation to produce the best work they were capable of to impress and entertain their peers.

Notice how she capitalizes on her students’ desire to perform to help them refine the presentation of their work.

With a few tweaks, this works in fourth grade, in eighth grade, in high school. Making learning fun is not limited to any particular subject or grade level. It’s not just about attitude. When you actively make learning fun, your students will have fun learning.

Rule Two: Build Routines, and Everyone Knows What to Expect

If someone visits a kindergarten classroom for the first time, it can seem chaotic. There are so many actions happening at the same time, and students are moving from one activity to another.

But if you spend time in a well-taught kindergarten, you quickly detect that there is a structure in place. That’s also true of all highly effective classrooms. When students are learning, routines provide a sense of stability and predictability in the midst of activity. It is a balancing act to provide enough variety to meet students’ needs and enough structure and routine for them to feel a sense of control and predictability. Despite any protests to the contrary, students generally thrive when there is a clear set of rules they can depend on and predict.

Rule Three: Keep Students Involved, and They Stay Out of Trouble

Beginning teachers often say they need to deal with discipline before they can focus on instruction. They quickly discover that if their instruction is busy and fast paced, many of the discipline problems disappear.

Most discipline problems occur during down time – periods of time when students are not actively engaged in instruction, such as the start or end of class, during class changes, during lunch or recess, and during transitions between activities within your class. That’s why it is so important to keep your instruction moving at a rapid pace. Don’t go so fast you lose everyone, but keep it moving.

Jason Womack taught 50-minute classes. Each day the first task for students was to copy the schedule off the board. He organized his instruction around a theme for the day and always listed 5 to 12 activities. Typically, he scheduled 10 five-minute activities. He wanted students to see, hear, and touch something at least twice every day. In a typical day, they would

“…see something (watch me or data); hear about it (listen to me lecture or use the closed-‐eye process [tell 4–7 min. story with eyes closed]…touch something (come back from wherever they went to [in their mind] and produce something based on what they heard; draw, write it, make a video,…or a puppet show). My goal was to give them information and let them internalize and give it back; not just force-feed info and make them regurgitate it, but to give them an opportunity to internalize and express it.”

He also ensured that his students were constantly engaged in learning.

Rule Four: Make it Real, and Students Are Interested

Helping students make connections between their learning and real life is a foundational part of engaged classrooms. In Eric Robinson’s classes at Saluda Trail Middle School, he taught students how to write a resume. Then, he and his colleagues worked together to show them how to select colleges/universities, the types of degrees, and job descriptions.

They do a rough draft of the resume, then after we work out the mistakes, the students type their resumes along with a cover letter. Once I approve the typed resume, the students set up an interview with an administrator or teacher who is part of the interview team.

Prior to setting up an interview, each student has a class in interview etiquette. In this class, the students learn how to enter the door to the interview, how to talk, eye-to-eye contact, body posture, and good communication skills with the interviewer.

Students are never too young to experience real-life learning.

Rule Five: Do It Together, and Everyone Accomplishes More

When I was teaching, I wanted my students to work together in groups. I have always believed that we learn more together than we do alone. But my students weren’t convinced. I heard more complaints about group work than anything else I did.

One day, I shared a newspaper story that reported the number one reason people are fired from their job is because they can’t get along with their coworkers. My students were amazed. They were convinced that people were fired because they couldn’t do the work, so hearing that getting along with others was an important part of working was new information to them. After that, I met less resistance to group activities.

Teacher Connie Forrester explains:

“It is important to me that I provide opportunities for learning that are authentic and based on a framework of inquiry. I believe children will be more motivated to accomplish a task that they feel makes sense and is meaningful…. Group work is one way I achieve this goal. I work hard all year to help the students see we are part of a team – that all that we accomplish as individuals affects all that we accomplish as a group.”

That’s the key to effective group work: students working together around an authentic task, building on each other’s strengths!

Engagement is critical

Student engagement is one of the most critical aspects of our classroom. When students aren’t engaged, they simply aren’t learning. By adjusting our instruction, we increase the opportunities for students to be engaged.

What do you do to keep your students eagerly involved in learning?

![Rigor Is NOT a Four-Letter Word [Book]](https://images.routledge.com/common/jackets/crclarge/978020370/9780203704240.jpg)

Making teaching fun will encourage participation. Working in groups helps teacher to monitor how much is being internalized.

collaboration is the key