Crafting and Scripting History Lessons

A MiddleWeb Blog

Many teachers struggle to find a balance between crafting good lessons plans and staying spontaneous in the classroom. And we often ask ourselves, “to what degree should students’ interests and needs shape this lesson?”

Many teachers struggle to find a balance between crafting good lessons plans and staying spontaneous in the classroom. And we often ask ourselves, “to what degree should students’ interests and needs shape this lesson?”

Having gone through the DeLeT training program, we are huge proponents of constant reflective practice. After much reflection and adjustment, we found ourselves getting into a groove of history/social studies lesson planning that works for us. Here’s how it looks:

Step One: Big Picture

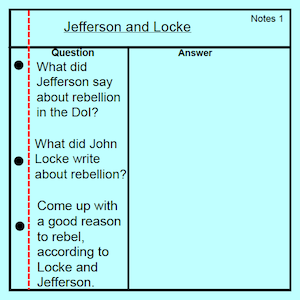

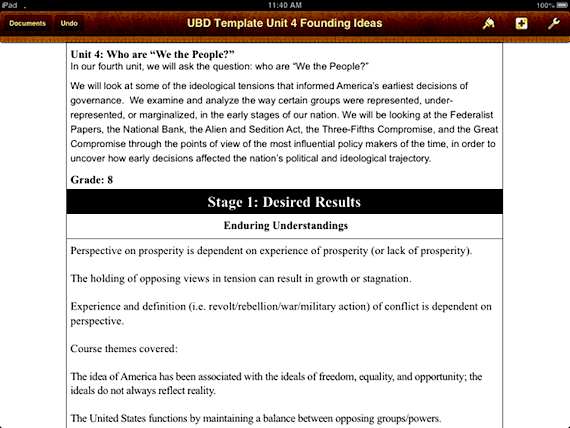

We pretty much follow Wiggins and McTighe’s Understanding by Design process — starting with enduring understandings along with essential questions and assessment, then working our way backwards through the various elements of the lesson plans.

We do a unit overview for each history unit that includes “big picture” pieces – and then get into the meat of the lesson planning around content and themes.

Step Two: Smartboard

We are lucky enough to work in a school that has Smartboards installed in every classroom; this is, of course, not the case for everyone. Smartboard software is great for scripting out lesson plans because it allows for a screen-shade to hide and then reveal parts of a lesson on a single page. We worked with Aaron Brock (contributor to this blog) to craft many of these units and lessons, and he does his on PowerPoint, usually. We don’t feel restricted to a particular tool.

We script our lessons out on Smartboard software because it allows us to stay on track — unless we purposefully decide to take the lesson in another direction for clarification purposes or student needs.

Another MAJOR advantage of scripting lessons out is that students are able to see the question that is being asked, as well as hearing it. Teachers don’t have to turn their backs on students to write directions out on the board and don’t have to remind students of what question they are meant to be discussing, over and over. We have found this to be incredibly helpful with all students, but obviously the most help to students who have auditory processing challenges.

Our lessons tend to be experiential and collaborative; students work together to uncover information. The teacher is not seen as the source of all information, but rather a facilitator.

The lesson ends with some kind of closure: a discussion, reflective writing, exit card, etc. in order to assess and wrap-up the day’s concepts. The closure, as with the rest of the lesson, is scripted out so that any directions the students are following, or questions the students are answering, are right on the Smartboard.

Lessons are always scaffolded so that the smaller parts of the unit come together for the larger assessment at the end; our goal is to make each lesson a smaller piece in the larger unit puzzle. This culminates in the unit assessment.

Step Three: Haiku

This allows for students to review lessons and activities, or catch up due to absence. (As the UBD overviews are for teachers, not students, they are not made available for them to see.)

Step Four: The Purple Notebook

From past experience, we have learned that it is vitally important to be as specific as possible when explaining to your future self what changes you want to make. Too often we have been flummoxed as to what we meant by “change the rubric” and similar vague entries, that we were, at the time, so sure were self-explanatory.

There are so many parts in the lesson planning process that we left out of this post – it was just getting too long. The actions that go into crafting good units and lessons seem almost endless. Please let us know if there is any point we can expound upon or clarify.

Better yet, share something from your own lesson planning techniques.

Hi, I am very intrigued by this post. I opened the PDF (the “usual” lesson), and it looked like the handout you would give students to work through the lesson rather than the lesson plan itself. Do you also have a separate lesson plan that mentions, for example, objectives and standards and how much time you spend on various aspects of the lesson? If so, could you post that, too (or Email it to me at literacycookbook@gmail.com)?

Thanks,

ST

Thanks for these great tips. I would offer to continue or expand the use of various modes of intelligence to engage students in history with their own styles of learning and to incorporate more cultural historical facts beyond the limitations of most history books. I absolutely hated history up until college because what we learned in school did not reflect thorough research history and enhance it with other facts that students do not learn beyond the “heros and holidays” scenario. There was also not enough realism and connection to history as it unfolds today.