Real-World Activities for Adolescent History Students

A MiddleWeb Blog

Every year, at least half a dozen students ask me some variation of the following question: “Why do we need to take history? How am I going to use this in real life?”

It is a question any good history teacher can answer, but often not to the satisfaction of the adolescent mind. An educated adult can see the value in studying the patterns of human behavior in history and understanding the origins of our various social systems. The average middle school student is concerned with events within a time-space radius of ten minutes and ten feet in any direction.

There is little room in their worldview for the big picture. Making real-world activities meaningful for teenagers often means shrinking the big picture to fit this limited frame of reference.

It’s a Small World

Because of the developmental narcissism of my students, I try to make sure any real-world activities resonate with their immediate interests. While I believe that students should be aware of the social, political and environmental challenges that they will face as adults, most of these issues do not resonate with the average adolescent.

My goal is to show them how they can utilize the skills and knowledge acquired in the classroom to analyze, plan and execute a plan of action in pursuit of a concrete goal. This is only meaningful if the students can envision that goal and are genuinely invested in obtaining it. Because my students spend more time in school than any other single place, I prefer real-world lessons that are centered on the school site itself.

Petition, Assemble, Speak

My real-world activity this year was centered on the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Each of my classes created and printed a petition that they presented to the school administration during a peaceful assembly outside the main office.

To create the petition, I first had students brainstorm their concerns about the school. As a class we narrowed these down to a single core issue. While a petition can include many complaints and demands, I did not want the petition to read as a laundry list of individual grievances. Part of the purpose of this activity was to teach students to identify what is most important to them as a group. I wanted students to get outside of their heads individually and start thinking about their needs collectively.

Once we had settled on an issue, we wrote the petition as a class. First, students worked in teams to discuss and write why they believed the particular issue needed to be addressed. While I asked students to be honest, I reminded them that administration was more likely to respond to reasonable language. When we began writing the actual petition as a class, I had each team suggest ideas, while I typed their ideas into a document that was being projected for the entire class to see. This gave me an opportunity to help students rephrase their ideas in academic language, with the entire class witnessing the editing process.

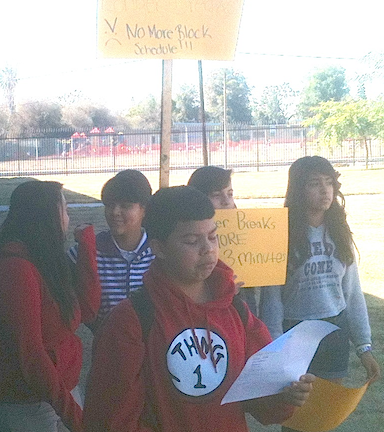

The next part of the activity was a peaceable assembly outside of the principal’s office. I alerted the administration, so that they would expect each class, and asked that an administrator make time to hear the concerns of my students. Students made signs related to their issue, and then we marched to the front office.

Getting the administration involved gave the activity more meaning for the students; they were being heard by adults who rarely took the time to seriously listen to their concerns. I asked that the principal come out of his office and listen to one of the students read the petition aloud. This helped make the whole activity more concrete. The students knew that the principal had heard their concerns, and they could see his reaction to the petition.

After the peaceable assembly, we returned to the classroom and engaged in an informal discussion about how students felt and what they believed the prospects for change were.

Getting real about patience and persistence

Patience is essential in the arsenal of any activist, but most of my students are wont to give up on something when it does not go right the first time. They do not understand that sometimes it’s not what you asked for, but how many times you asked for it.

Whether or not the students ultimately create a change in their circumstances through such an activity, the ability to analyze discontent, and then channel it into something productive is a skill that will prove useful throughout the life of any person.

So many of the students I work with act out in self-destructive ways because they have never been taught how to constructively approach adversity. Providing students who struggle with self-control (as a great many middle school students do) with a model for redirecting that energy toward positive change has the potential to be life-changing for some students.

Such a pleasure to see your enthusiasm for learning history come into action with your students! Connecting new knowledge, skills, attitudes with their present lives is the only way to teach!! Dewey would be proud of you.