Anne Jolly & Hands-on Science

With support from the National Science Foundation, award-winning science educator Anne Jolly is helping the Mobile Area Education Foundation develop hands-on science activities for the middle grades that will fully integrate with national standards. She talks about that and other current work and her journey from bench scientist to middle grades teacher, Alabama state teacher of the year, school learning teams expert, and all-around teacher leader.

1. Top 10 lists are all the rage. Give us the top 10 milestones in your professional career, with a few sentences about each.

All of my career “milestones” grew out of the following realizations:

I need help with my teaching. I picked up teaching certification but didn’t actually learn much about how to teach. I was able to establish good relationships with my students easily, had few classroom management problems, and taught my heart out – the way I was always taught. Fortunately I was entertaining (by this time I was teaching science in another school) and liked doing labs with the kids, but not only were my supplies limited – I was limited in knowing how to really engage the students in learning.

When you put a question on a test, “Explain why the moon causes tides,” and the answers you get back are along the line, “It’s in Chapter 4,” then you know you’ve got problems helping kids understand. The next milestone occurred when a couple of science teachers in another school decided to build mentoring relationships with new science teachers in the system. They certainly expanded my horizons, and I began to build professional relationships with other colleagues in the system.

We (and some other teachers) met regularly. We sent out a quarterly newsletter to all science teachers in the county with ideas and insights. We conducted workshops for fellow teachers. And in the process I got the help I needed. I learned more from my colleagues – even though they were at a different school – than from any other source.

I need to be more involved in the world outside my classroom. Somehow along the way I became the state teacher of the year. This milestone launched me on a whirlwind tour of speaking and meeting folks in government and business, as well as education. At that point I realized that I didn’t know much about the world outside of my classroom, and that world mattered.

The policies and decisions people outside my classroom made affected my teaching, from the amount of money I got for supplies to the curriculum I taught. People in businesses hired my students and needed them to be able to do specific things, like recognize and solve problems and work with others. And I needed to be able to communicate with these people on behalf of teachers. I buckled down and took on a number of roles during that year that involved me with the folks who fund and support public education.

Teachers need a voice in policy making. I didn’t have to look hard that year to realize that the voice of teachers — those most knowledgeable about the classroom — is normally absent at the policy table. So after my teacher-of-the-year stint ended, another milestone was around the corner. I became co-founder and executive director of the Alabama State Teacher Forum, an organization dedicated to getting the voice of exemplary teachers into the policy arena. The A+ Education Foundation hired me for a year to get funding and programs underway for the Forum. We conducted workshops, gave speeches, and established an annual Outstanding Educators Symposium which brought teachers together with other educators, business people, and politicians to discuss education policy issues. There we had structured discussions and informal discussions, and this forum continued for over a decade. We were successfully able to influence some education policy, and some business leaders began to invite teachers to the table when discussing education.

Most of the low achieving schools were in poverty areas. The first school I went to had no science equipment. Not even a beaker. One school itself was so old that the walls in some classrooms consisted of one layer of brick. In another school the library hadn’t been open or used by students in two years and the outdated books on the shelves included a set of 1948 encyclopedias. In every case except one, the schools I worked with were in dire need of resources. I threw my whole heart into helping teachers and kids in those schools.

But in my heart I knew that I wasn’t making the difference they needed. They needed a lot of people to care. (I’m happy to say that, today, while there are still discrepancies among schools in terms of resources, the gap problem has improved.)

Teachers can make a difference at many levels. For several years during this time my milestone included serving on national and state commissions and committees, I served on boards of directors for state organizations and business organizations. I felt that teachers were beginning to be included and teacher voices were beginning to be valued more, especially at the national level at that time. But it was time for me to return to my roots – the classroom. I could make a difference in a number of ways, but I needed to look into the eyes of students again.

Teachers must learn together and learn continually. I took a position teaching science in a new school designed so that teachers worked together as teams with the same group of students during the day. Our team even had a period every day just for team planning. We were so excited about that! At our first team meeting we brought in our notebooks and pencils, sat down with a cup of coffee, looked eye to eye, and . . . . what next? What should we be doing and how should we be planning? What could we do as a team that would make a difference for our students? We didn’t even teach the same subjects.

That launched another career milestone. The next year my principal asked me to work at the school as a professional development director and figure this team thing out. Professional learning communities were barely on the radar, and I knew little about them. I read, studied, worked with the teams in that school and in another school that volunteered for this initiative, and collected data and information. Finally, after a year, we had come up with some processes for working together and assessing our teamwork that began making a difference for students.

For the past 11 years I’ve worked with professional learning teams, and eight of those years I developed, implemented, and assessed them through the SERVE Center at UNC-Greensboro. During that time I wrote a book to describe the process for establishing, supporting, and assessing these teams in enough detail that others could implement them.

Virtual communities provide a base of support and encouragement, and a forum for teacher voices. During my time with SERVE and since, I’ve discovered that through the miracle of the Internet I can talk, grow, and learn with education colleagues. The evolution of virtual learning communities (VLCs) has become a major milestone in my life. I am a member of four teacher virtual learning communities, and I help to moderate two of those. On one of these I am working with fellow teacher leaders (some of us former teachers) to create a new community of exemplary teachers in our state. These VLCs are energizing and informative. They widen circles of collegial relationships. Through these VLCs teacher leaders emerge. Some mentor other teachers and many begin sharing expertise and insights through blogs. VLCs can mobilize a critical mass of teacher voices around important education issues. They can provide a forum for teacher voices as a part of a national conversation.

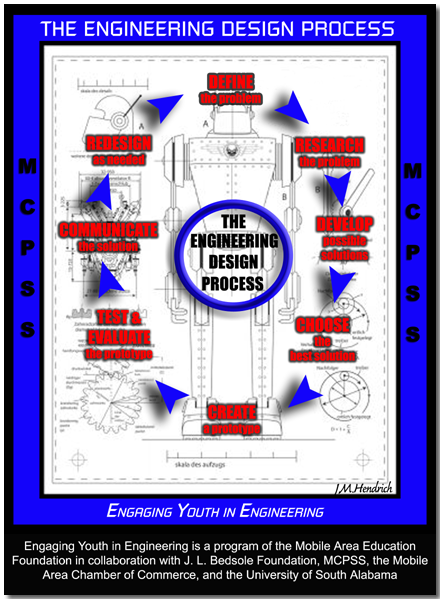

Students can act as engineers. If this one sounds like it comes from out of the blue – well, it seemed that way to me as well. This milestone circled me around to a student focus again, but in a different way. I now help to write middle school curriculum modules that integrate math and science around an engineering challenge. I’ve learned again that students are amazing. They will take on a challenge that has value for them, and they can solve it in creative and unique ways. I’m also working with Mobile County middle school science and math teachers to help them write STEM lessons, incorporating their course of study objectives, to be distributed and used throughout the school system. These particular jobs take the majority of my professional time presently.

Retirement is a figment of my imagination. I’ve officially retired twice. And I’ve flunked retirement twice. Retirement isn’t real, at least not for me.

2. Over the past couple of years, you’ve been working with NSF grant support to develop a hands-on science curriculum for the middle grades. Please tell us something about the work, why it’s needed, what some of the units/modules look like, and how they might address not only science per se, but 21st century skills.

Actually, I’m working with a team to write engineering curriculum modules that closely integrate math and science – and also engage math and science teachers in working together. This work is done through the Mobile Area Education Foundation and is directed by Susan Pruet. who is in charge of the Engaging Youth through Engineering (EYE) program for the Foundation. Also involved are Carolyn DeCristofano and Deb Dempsey of Blue Heron Education Consulting, Melissa Dean and Judy Duke of the Foundation, and others. With this NSF grant, we are developing, piloting, revising, field-testing, and formally evaluating the impact of nine engineering modules over a period of five years.

These modules are being written, and will be evaluated, based on seven specific outcomes for students:

- Apply math, science, and technology through an engineering design process

- Analyze and interpret data

- Identify, articulate, and solve problems

- Communicate effectively

- Work successfully in teams

- Use the techniques, skills, and tools necessary in the workforce they will enter

- Recognize the need for ongoing learning and make learning a part of their lives

Each module lasts about a week and so far they have been so successful that the school system has incorporated engineering language and objectives into the math and science curriculum. (In fact, in partnership with EYE, the school system is now designing middle school STEM lessons – one per quarter in science and in math – written by teachers.) We involve the business and higher education communities heavily in conceptualizing each module and in helping with the implementation as well.

I should note that implementing these modules involves providing teachers with a full day of professional development for each module. The materials are provided for the teachers during this design and testing period, and several former teachers work with this program in the schools to support the teachers when they implement the modules. Writers observe the implementations to see what works well and what needs revising.

In a watershed module, you would see each team of students designing and building barrier systems to slow the sediment discharge rate from a model streambed. They would test the model, calculate the needed data, and then redesign. Students would compare the data from all classes (via Excel) and determine what barrier properties seem to be most successful.

In a life science module you could watch student engineering teams figure out how to design a model clot catcher that will stop a clot from passing through a model inferior vena cava to the lungs. Again, they would test this system, calculate and evaluate, and redesign the clot catchers to be more successful.

Or, you might see teams of students figuring out how to design a growth system that can be used to produce a maximum amount of plant mass (the output) with minimum amounts of inputs (soil and water). Why? Because they need to be able to transport such a system to Mars to support future colonies that NASA will transport. After making input choices and assembling their growth chambers, students would monitor and record aspects of their team’s plant growth for two weeks. The output data from the growth chambers would be compiled across the grade for analysis and decision-making.

3. You’re the author of a popular (and practical) guide for school-based professional learning teams (PLTs). What’s your analysis of the state of the “professional learning community” movement in U.S. schools? Good, bad, ugly?

Yes to all three.

Good, because collaboration around a common focus is by far the most effective way to engage teachers in ongoing learning about how to address student needs. Some schools are successfully using this approach. (Edenton-Chowan School System in NC for example.)

Ugly, in that like many good initiatives, schools may be too quick to say, “Oh, that doesn’t work.” They don’t realize that building the relationships to make PLCs work isn’t instantaneous. So they give up on this initiative. Teacher learning once more becomes a series of spurts and stops, mostly conducted in mass during summer workshops while teachers are away from the real school setting and have no students. In some schools the players are simply not willing to make the commitment to bring about PLCs. They aren’t wiling to commit to providing necessary training and support, needed resources (including time), the incentives, and the school support structures that are needed.

4. If you’re still working some with PLTs, we’d like to hear your take on the value/necessity of teachers developing their own personal learning networks, participating in virtual communities of practice — the importance of “connectedness” with expert/collegial communities beyond school/district. Do you see this becoming more commonplace?

I’m still doing some PLT work. I’m sharing what I know through training sessions, giving schools tools and materials to work with, observing and documenting how the process works for some schools, and developing new tools for troubleshooting the process as needed.

Virtual learning communities are definitely becoming more commonplace for me and many other educators, and I highly recommend them as one method for learning teams to keep their momentum going. Relationships can continue to blossom and grow through online communication, as can learning and planning. Virtual communities can help to keep learning teams on the front burner; to keep the energy going; and to provide ideas and support to team members.

Professional learning teams (or communities) are vitally important. Isolation can take you just so far – you can’t move beyond the confines of your own thinking if you listen to and learn from no one but yourself. Building collaborative relationships with colleagues matters and it matters a lot. PLTs (PLCs) provide teachers with opportunities to study and learn together in order to become better teachers, in areas where their students need them to be better. They provide opportunities to do this in the context of the school day. So the changes they make in instruction are based on real students in their real school setting.

5. What are 4-5 changes you’d like to see over the next 10 years that you believe would make schools better places for kids to learn and become caring and capable citizens?

Avoid keeping high stakes testing as the driver for improving schools. It isn’t.

Become more collaborative – focus on building strong teachers and keeping them current.

Change the way students are taught – give them access to technology and the Internet, and incorporate these tools into their learning seamlessly. Give students relevant curriculum that prepares them for ongoing learning in the workforce.

Make school less hectic for students – slow down the pace and create time for more in-depth learning in needed areas. Offer curriculum that will help those entering the workforce from high schools to secure high-tech jobs. Give more opportunities for positive interaction, expect positive interaction, and practice techniques for working together and for learning together.

6. What’s next for you?

I have a philosophy by which I’ve always operated. I walk through open doors and I find myself in amazing places. I still use that philosophy. So my upcoming possibilities:

• I may be writing another book.

• I may be working with a new school system to help them with a dynamic learning design for students and teachers.

• I will continue moderating some VLCs. I will also continue to help with the “birth” of a new state VLC and will advocate for teacher’s voices as the most important part of education reform.

• I continue to work with the STEM initiatives by writing middle school engineering curriculum and working on the board of directors of the Alabama Mathematics, Science, Technology, and Engineering Consortium.

• I continue to lead PLT conferences and work sessions.

• I am heading up the effort to convert an old armory into an energy efficient, state of the art library/community resource center in the small, underserved community where I now live, and to involve other small communities around us in that effort.

Oh – and I also plan to keep reading. Just finished the Clockwork Universe by Edward Dolnick, The Black Hole War by Leonard Susskind, and I’m now reading The Uranium Wars by Amir D. Aczel. Love that Nook!

Photos: Education Week Teacher, MAEF, Learning Forward.

You can follow Anne on Twitter @ajollygal

What a fantastic interview! As someone who has the good fortune to work with Anne, I know that her words and insights are authentic. What I did not know was the full story of her journey and the depths of her current invovlement in education. What a gift she is to the education community!

If I were starting out in my career as a teacher/educator, I would print this and post it on my refrigerator as a guide and inspiration for my professional aims and my life. In fact, I’m still going to do that, even though I’m 23 years into my career. I see I still have lots to learn and lots of time to learn it, given that retirement is only a fiction. Thank you for posting this interview.

(P.S. I think Anne has captured the power of engineering education quite beautifully.)