Cultivating Passionate Learners in Common Core Classrooms

by Pernille Ripp

by Pernille Ripp

I remember the days of clutching my science curriculum in one hand while trying to write on the board with the other. Always casting glances at the script — what was I supposed to say next? And it wasn’t just science, it was pretty much all of my lessons. I’d read from the paper and try to make it sound like I knew what I was talking about.

It was not lack of preparation but lack of confidence that haunted me. I thought the curriculum materials said it best, so rather than exerting ownership of the lesson, I would adopt the curriculum writers’ language as my own. I tried to render it in natural speech, but as anyone who has ever taught this way knows, if you haven’t thought something through in your own words, you will sound contrived and fake.

Then it was “watch me as I read this aloud to you.”

As any new teacher knows, this take-and-read instructional strategy is part of surviving the first year. We borrow others’ lesson plans or scripts and try to make them our own. Often, we are barely treading water, enjoying the (mostly) exhilarating ride but often not knowing when we will catch our breath or actually have time to think something through.

Even so, I wish I’d had the guts that first year to go out on my own a little bit. To trust myself more to deliver a good lesson. To begin asserting my own identity as a teacher who means to be great. The biggest barriers were confidence and time, of course, but I see now that I could have allowed myself to believe there was a better way.

Now it’s all about the students

I didn’t transform my teaching overnight. I began by doing some things a little differently and watching to see what happened. There was a lot of experimentation and keeping my fingers crossed. I would concoct an idea, present it to the students, wait for their feedback. Then we’d make adjustments and keep moving forward. And it was invigorating! There’s something incredibly life affirming about not being sure exactly the direction your teaching and learning is going to take and only knowing where it will end.

Often when I share this sense of exhilaration about student-driven learning with other educators, they think I am either (a) delusional or (b) that I must teach in a world that is not dictated by standards. While I may be guilty of being very optimistic, I teach in Middleton, Wisconsin, in a public elementary school that has to follow all the rules and regulations.

Some may feel that the standards or curriculum being cast upon us and our students stifle any form of creativity. I don’t agree. While these things certainly establish limits, I believe we have to find our own freedom and creativity within them.

Student choice and standards too

I know that time is short for all of us, but we must find the opportunities within our standards-driven curriculum to let students explore. In science, I look at the unit’s end goal and work backwards from there. One year, while studying crayfish, I knew the end goals were for students to understand the crayfish life cycle and gain a deeper respect for living creatures. Those are very broad goals, which is wonderful for this type of learning.

And guess what? It took the same time as the lessons proposed in the curriculum, and students were engaged the whole way through. More than that, they were not simply consuming information but problem solving — a skill we’re expected to nurture and promote.

I realize it’s not always possible to have our students roam so free. But even our most dictated curriculum can be manipulated in ways that allow us room to explore and create. We have to know our end goals, or standards, so that we can think backwards and try to visualize the most exciting path to getting there.

What You Can Start Doing Today

1. Begin at the end. Ask yourself where you need to arrive at lesson’s end and then figure out the essential knowledge that students should uncover along the way. Keep your answers front and center throughout the process so that you know whether the path your learning community is taking is getting you there.

3. Let them think about it. At the end of the year, I like to have a culminating writing project that is combined with a created component. I often foreshadow it a month before we start it. The reason is simple: students need time to figure out what they would like to create that’s both true to themselves and adequate to meet our goals. Because we start preparing our minds for this early, students do not feel rushed to settle on a project type (from a list of suggestions), and they also have time to dream up something original. This leads to better engagement and much better projects.

4. Give it time. Both you and your students need time. I sometimes get dejected when an idea doesn’t work right away, but later realize that it can work or it just needs tweaking. This shared planning of the learning experience may be a completely new process to you or your students, so I think it is vital to dedicate enough class time to get it started well.

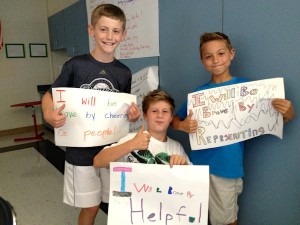

5. Plant the seeds of ownership early. Throughout the first week of school, I am already encouraging students to speak up and add their ideas to the classroom. With my promoting this early on, students get used to being part of the discussion and have an easier time migrating from (for example) a discussion of classroom norms to actual curriculum.

6. Be prepared for faltering and failure. Even with the best intentions, and even when we follow a script, sometimes lessons do not work. So be prepared in case the discussion or project does not go where it needs to and try to steer it back before it is too late. If you find out too late, then make it into a learning opportunity. In my classroom, when something doesn’t go as we had hoped, we always reconvene and pick it apart. Some of our best learning moments come from these student-led but teacher-guided discussions.

7. Know your standards. You have to pick them apart to make sure you are covering them. Try searching the internet for teacher-oriented translations; lots of educators are breaking down the Common Core in useful ways.

9. Give students opportunity for leadership. I switched to student-led parent conferences three years ago and have loved seeing students take ownership of their learning and their goals. Parents feel informed, and we start a dialogue rather than have me deciding everything. (For more information on student-led conferences, see this page.)

10. Be open. Your classroom learning environment may work in a different way than others around you, so be open to discussion. In fact, when it comes to parents and administrators, you should be initiating the conversation. It is always much easier to gain understanding and acceptance for a different approach if others know you are still doing your job.

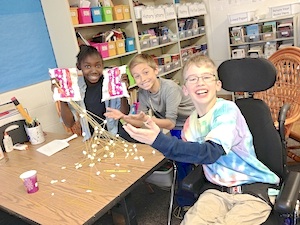

[Photos: Pernille Ripp]

Pernille Ripp is a 5th grade teacher in Middleton, Wisconsin, where she lives with her husband and four children. She is a co-founder of EdCampMadWI and the creator of the Global Read Aloud, a literacy initiative that has connected more than 200,000 students worldwide since 2010. Pernille was selected as a Microsoft Hero of Education in 2013 and was a finalist in GOOD’s 2011 search for the “Most Innovative Educator in America.” She writes regularly about what she’s learning at Blogging Through the Fourth Dimension.

Ms. Ripp you are absolutely right on so many counts. The standards are like taking a road trip across the U.S. There are certain places you “must” see without which the road trip wouldn’t be complete. On the other hand how you get to where you’re going and the interesting stops you make along the way are totally up to you, the teacher. We as educators can give ourselves the permission to be innovative and creative. Teaching becomes liberating and incredibly exciting and we don’t do the driving either. The student is in the driver’s seat, and we, as a back seat ride along, pose the questions and lend a guiding hand. Let us not forget that the student learner cannot drive as fast nor can they react as quickly to those bumps and turns in the road. We must be gracious in our critiquing, supportive and nurturing in our understanding. We are there to “assess and monitor” not “test and punish”.

Thank you so much for your comment and reading the excerpt. I loved your line about giving permission to be innovative, I couldn’t agree more. Often we think it is not correct teaching if we have fun with the curriculum, that there is no way we could cover everything we needed, and yet when my students are the most joyful they also seem to learn the most.

Your ideas are not exclusive to Common Core, but encompass good practices for innovative teaching. You were probably doing similar things before Common Core.

Yes I was, but I think many teachers are wary of doing some of these things now with more standards bearing down on them. And I certainly had to reinvest into this teaching rather than go backwards.