Too Many Topics?! Try the DBQ Approach to Research Papers

by Sarah Tantillo

by Sarah Tantillo

One day when I sat down with a high school English teacher who was revising her curriculum, she presented this problem: “Last year, the research paper took forever. And the results were terrible. I can’t go through that again. We need to do something different.”

Cutting out the research paper was not an option. So we tried to figure out what hadn’t worked.

“What was the assignment?” I asked.

“They had to write about a controversial topic,” she said. “And a bunch of them wrote about abortion, of course. Some of them wrote about drugs.” She shrugged. “Even though I collected their notes and outlines, their papers just made no sense.”

I nodded. I had been in her shoes and knew exactly how she felt. Awful.

How do we get into this fix?

We identified two primary causes of this problem: (1) The choice of topics—in fact, the assignment itself was too broad; and (2) Students didn’t know how to build a coherent argument— in part because they didn’t know how to pull out relevant evidence and explain it. In a moment I’ll explain how we addressed these two issues.

This scenario is, unfortunately, far too common. Because middle and high school teachers know that giving students choices can strengthen their investment and interest in assignments, they often make the mistake of offering too many options or options that are too broad.

“Write about whatever you want” (more or less the equivalent of “Write about a controversial topic”) almost never results in a well-argued, well-supported research paper. In fact, with a topic as the focus, students fail to realize that they need to build an argument.

By contrast, question-driven assignments push students to build arguments in response. The difference is stark. Compare two papers: one called “Euthanasia,” the other “Why Is Euthanasia Controversial?” The former could say almost anything; the latter already has a clear focus.

The teacher I was working with decided to design a question-driven assignment. And to be sure her students developed the reading and writing skills they needed, she also decided to limit the texts they would use so that she could do lots of modeling and closely monitor their progress. In short, she planned to use the Document-Based Question (DBQ) Approach.

The why and how of the DBQ

Though originally the purview of history and social studies teachers (they were first used on AP History exams and New York State Regents social studies exams), DBQs have begun to appear more widely across the curriculum.

In fact, more and more teachers have started to realize that DBQs can prepare students in any grade or subject to be more effective at reading texts and writing about them.

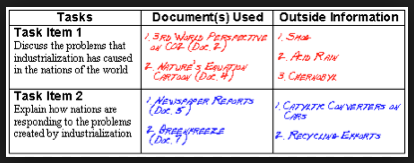

The DBQ approach is simple: you give students an open-ended question and a half-dozen or so relevant texts, then require them to build an argument using the documents as evidence. It’s easier than a research paper because students don’t have to look for the documents. More important, it gives you a way to guide and monitor students’ progress since everyone is working with the same texts.

You can and should model each step, from how to closely analyze different types of texts (essays, political cartoons, graphs, charts: anything!) to how to identify relevant evidence, how to organize ideas and information, and how to synthesize evidence and explanations logically to build compelling arguments.

By using an array of texts, you can also work on increasing text complexity. As Bambrick-Santoyo, Settles, and Worrell note, you can “embrace the CCSS’s ‘ladder of text complexity’” by beginning with a simple passage on a topic to introduce key words, then moving into a more complex passage that requires the same content knowledge but also adds new language.

This concept of starting with essential vocabulary and increasing complexity from text to text is important to apply throughout your instruction, of course, but it is particularly easy to see how it can work with the DBQ approach, where students read multiple texts that address the same question.

Differentiating DBQ projects

You can also differentiate DBQ projects in various ways. For example, you could group students based on their reading levels and supply them with relevant texts of different complexity (recognizing that while they might start in different places, they all need to move forward) so that they all have something to read independently, in addition to the shared texts that are on grade-level.

The reading and vocabulary-building work led to the ultimate writing assignment, which was an essay addressing these questions: “What were your historical figure’s greatest contributions to the Civil Rights Movement? In what ways did your historical figure show grit and determination?” Students also worked in groups to create timelines and posters, and participated in debates.

Worth the work

I’m not going to lie: creating this project was a ton of work for the teachers, but once it was done, they could use it again because it worked wonderfully.

If you want to add a research component to a DBQ, you can also teach some mini-lessons on research steps (such as evaluating websites for bias, and so on) and require students to find some number of additional documents to support the ones already given.

Here’s the bottom line: taking the DBQ approach—in any grade or subject—can ensure that students learn how to read and write effectively about important questions in your class.

______

Sarah is a literacy consultant who taught secondary school English and Humanities in both suburban and urban public schools for fourteen years, including seven years at the high-performing North Star Academy Charter School of Newark. She’s also author of The Literacy Cookbook and offers professional development help at her blog of the same name.

For more information on the DBQ approach, esp. for history/social studies teachers, check out this page on The Literacy Cookbook Website: http://www.literacycookbook.com/page.php?id=122

I enjoyed reading this article. I teach GT at the elementary level and all grades have a research component. I like the DBQ approach. It narrows it down and the children present a better response and stay focused better.

The scaffolding is so important! Students don’t know how they “synthesize evidence and explanations logically to build compelling arguments.” When they have multiple, conflicting points of view, they have the motivation and the need to read carefully and take notes, see “Why should I take notes?”

http://www.librarymediaconnection.com/pdf/lmc/reviews_and_articles/featured_articles/Abilock_January_February2014.pdf