Teaching Literacy Skills with Quality Comics

A MiddleWeb Blog

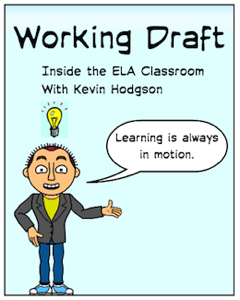

Imagine, if you will, a picture of me, with a lightbulb over my head. Got it?

Imagine, if you will, a picture of me, with a lightbulb over my head. Got it?

What am I doing? Thinking about what to write for my Working Draft blog, right? Right. What were you doing? You were using what is known as “emanata” to translate a visual symbol into a concept. The lightbulb over my head informed your thinking.

The flood of graphic novels into the hands of young readers in the past five years or so has been an amazing shift to watch from the perspective of a classroom teacher. Magnificent works of art – like the Bone series by Jeff Smith and Zita the Spacegirl by Ben Hatke – are transforming the reading experiences of many students, drawing in reluctant readers and connecting art to writing in powerful ways.

I have entire bookshelves in my classroom dedicated to hundreds of graphic novels and non-fiction texts (a perk of reviewing graphic novels is that I get to share them with my students).

Reading graphic stories requires a skill set

While I applaud quality books of any sort, I’ve closely examined how my sixth graders read graphic novels and I’ve talked with them about their experiences on many occasions.

I have discovered something interesting along the way: a fair number of my students don’t really know how to “read” a graphic novel because they have never been overtly taught that skill.

Instead, they’ve had parents and teachers simply put graphic stories in their hands, perhaps out of kindness or perhaps out of hope that the reading bug will stick. Graphic stories, however, are more than pretty pictures with text. They are more than a few frames of the Sunday funnies.

How I use comics in my classroom

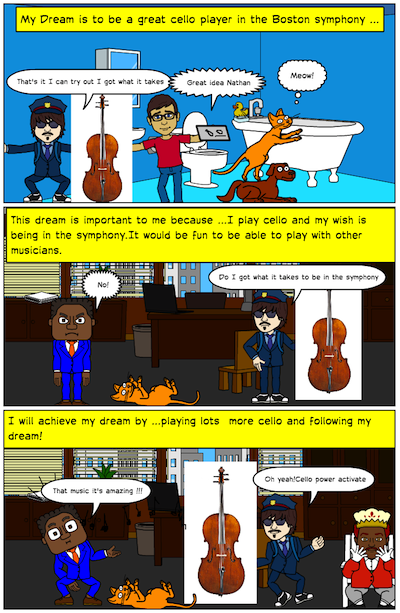

I regularly use comics with my sixth grade students throughout the year. In fact, our first big project is a Dream Scene assignment in which students have to envision themselves in the future and depict their aspirations in an online webcomic space we use called Bitstrips for Schools. It’s a powerful way to begin the year – an engaging art and writing assignment that introduces the rigor of the year ahead. And the Dream Scene projects provide insights into my new students in interesting ways.

As we move through the year, I weave in graphic stories as companion texts when applicable. For example, when we are exploring figurative language and the use of onomatopoeia, I dig out a stack of comic books (from Free Comic Book Day) and my students document the use of sound words to denote action on the pages of Ant Man, Gumby, Spiderman and others.

Finally, we get to the point where direct instruction around how to read graphic novels comes into play. This typically happens when we are reading either The Lightning Thief by Rick Riordan or The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg by Rodman Philbrick. This year we did not use The Lightning Thief, but we recently completed Homer Figg. Philbrick’s use of episodic storytelling as the narrator Homer seeks his brother Harold at the front of the Battle of Gettysburg provides a perfect entry point into making comics.

After the students have read the novel, I give a lesson specifically on the elements of comics. Years ago, I found an activity sheet at Time for Kids magazine that touched on the basics of constructing comics a la McCloud’s theories around graphic stories. Those basics include how to use dialogue and thought bubbles, the use of text boxes, choosing sound words to show action, and understanding some simple emanata ideas.

Collectively, we go through the graphic novel, page by page, frame by frame, noticing both the story and the format of the story, paying attention to the way the illustrator replays the adventure, the sequence of the story, the elements of time that require reader inference, and how the visual storytelling complements the text storytelling. We explore the art form with critical eyes.

And then my students become graphic novelists themselves.

Writing our own comics

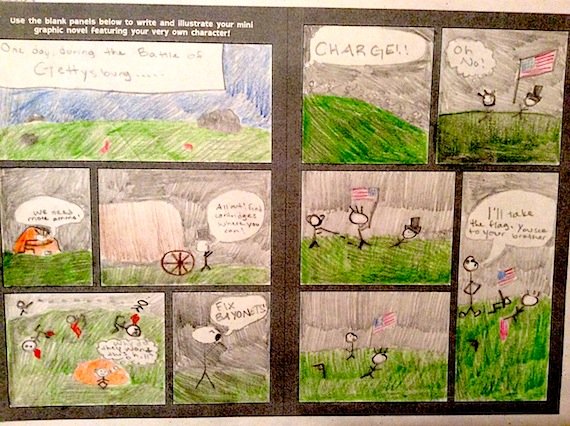

Our lesson involves dividing up The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg into sections, which we do collaboratively as a class, ignoring chapters in favor of episodes. Once this is done, each student is assigned a section, and their task is to render the novel into a graphic story scene.

While I do provide a basic template for creating a comic, they are free to create their own frames (not many do). They are expected to use some of the ideas we’ve discussed about graphic novel writing in their pieces, and when completed, the pages are put together to create a class graphic interpretation of the novel. Here’s the result:

We need to treat graphic novels seriously

This lesson reminds me that ideas we take for granted — that any student can read and understand a graphic novel, since it is mostly pictures — can lead to false assumptions. My classroom experiences suggest that direct instructions and targeted activities are needed to help students have a meaningful reading experience.

Graphic novels have a lot of potential for emerging and reluctant readers, as well as for those readers looking for challenging texts. I am wary of the recent flood of graphic stories, however; many have clearly been created to ride the wave of interest and money (along with the Common Core-aligned covers).

But when we turn the tables on these pale imitations, using rich graphic stories as our anchor, and then find ways to engage our readers as writers too, the results can be pretty interesting. By giving graphic novels the respect they deserve, we can go fairly deep into many areas of reading comprehension, critical thinking, and writing varied texts.

This was a very interesting article. Are there any quality graphic novels that you know of for 9th or 10th graders?

I used to review books for the now-defunct Graphic Classroom, but the site still remains (high five, Internet!). http://www.graphicclassroom.org/ You can search through grade levels and find reviews. There are so many great books out there, but also a bunch of junk that publishers put out, knowing that graphic novels are popular.

Good luck!

Kevin

Great article! I teach grades 4/5 at the American International School of Mali, and graphic novels have been the perfect springboard for struggling and reluctant readers–especially my second/third language learners. And to take the graphic novel to a whole different level, for 2 years now my class has also created a graphic novel for a service learning project, last year to educate local school children about malaria prevention, and this year to teach about rotavirus. My students do the research, write the script (collaborating with the local students as well), create storyboards, and assemble it all in the Comic Life 2 software. We print the graphic novel in both English and French, and distribute it to 3 local schools. Who knew a “comic book” could have so much impact!

Love seeing you cite McCloud’s work. He changed how I see graphica used in the classroom. Action research I conducted in the fall showed me the sophisticated skill set needed to understand the form. As with all literature, some are more well-written than others. Have you read Trinity about the atomic bomb? I think I actual understand fission better now.

Fantastic article! I was amazed at the creative and engaging strategies that you use to teach graphic novels to your students.

Great article! I’d like to hear from anyone using graphic novels in college classrooms.