Complex Texts: Let Readers Make Their Meaning First

by Dorothy Barnhouse

by Dorothy Barnhouse

The Common Core expects that students will do complex thinking about complex texts. As teachers respond to these expectations, now more than ever we need to look carefully at the messages our instruction is sending to the kids in our classrooms.

For example, a recent segment on National Public Radio highlighted what Kate Gerson of EngageNY, a professional development site developed by the New York State Department of Education, considers a “good” Common Core lesson.

The lesson, recommended for Day 1, Unit 1 of 9th grade (in other words, the first day of school), advocates that teachers start by unpacking the standards and then jump right into the close reading of a complex text.

The problem with this and with many other Common Core lessons, particularly ones that rely on the use of “text-dependent questions,” is that they emphasize reading as an act of unlocking meaning. The text is something to be “got.”

But the tricky thing about reading is that there’s this thing called a reader. Reading is, after all, making meaning — emphasis on the verb, to make. Think about what it means to make something: to build, construct, craft, compose. Makers tinker, they assemble things bit by bit with a good dose of trial and error, a lot of revision and some surprise – “voila” – “wow” – “look at that!”

And so it is with reading. A reader jumps into a text, paragraph one, chapter one, with only a hazy vision of where they might be headed.

Connecting the layers

Take the opening of To Kill a Mockingbird, for example. Let’s look at the first sentence — When he was nearly thirteen, my brother Jem got his arm badly broken at the elbow. We read the first part of that sentence — When he was nearly thirteen – not knowing who the he is. We read on, of course, and discover that the he is my brother Jem. But now we don’t know who the my is and so we read on to discover that.

This sentence requires the same kind of thinking that the first sentence does; it answers some of our questions but raises others. We’re required to think back – we’re getting more information about the narrator – but we’re thinking ahead too, with new questions. Who is this Dill and what’s this about Boo Radley and coming out? We don’t get any more information about Dill until four pages later or about Boo Radley until six pages later. Jem’s broken arm isn’t mentioned again until page 302, in Chapter 28, two chapters before the end.

This is, of course, how texts work — they layer information — and readers make meaning by holding onto and connecting those layers. We connect the Jem in the second clause with the he in the first, connect Dill on page 7 with Dill on page 3, the broken arm on page 302 with the broken arm on page 3, and so on. Back and forth, forward and back. Making meaning.

Each reader’s meaning is different

Reading in such a way requires a reader to be at the front and center of their reading. We have to be active, tinkering with the parts, fitting them together, drafting and revising as we reach toward a “voila.”

And here’s the thing: different readers make different meaning in texts. How could we not? I’ve demonstrated the way texts work on the most basic, informational level of To Kill a Mockingbird, but think of all the other details that can be connected in myriad ways across the pages of that book: the many different characters, the slew of images, the variety of events.

Readers will notice, hold onto and connect these pieces in different ways. Our processes of knowing and not knowing will happen at different points along the way.

But do we teach with this in mind?

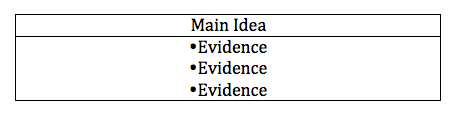

Unfortunately, we don’t usually teach reading in a way that reflects these processes. We tend to demand that our students “know” before they “notice.” We lift our language from the standards, asking them to “identify” or “determine” or “analyze,” to get the “it” and then “find the evidence” to “prove it.”

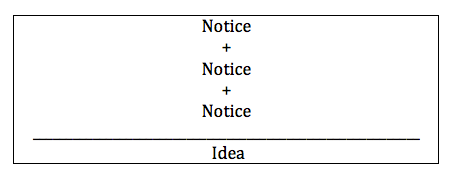

Such lessons have it backwards. We need to start with the “evidence “ – in other words, with what students notice — and allow them to build ideas – or what they know — from there. Imagine if scientists collected evidence after they had drawn their conclusions. Why do we insist on teaching reading that way?

We need to invert the popular graphic organizer from this:

to this:

When taking trumps making

In my own teaching, I’ve found that if I expect students to ‘know’ – to ‘get’ the main idea or theme or even make an inference – before I give them ample opportunities to ‘notice’, they tend to give me inaccurate interpretations.

Well, some of them don’t, but if I’m honest with myself, those are the students whose hands are always raised anyway. Most of the others slump in their seats, ask for the bathroom pass, play with their friend’s hair, agree with the person whose hand is always raised.

When this happens, it’s easy to default into heavy-handed, teacher-directed instruction. “They’re not getting it!” I panic. The ‘it’ gets pushed to the front and center of my teaching and my students get left behind. When I supply the ‘it’, they are taking meaning, not making meaning.

The power of noticing

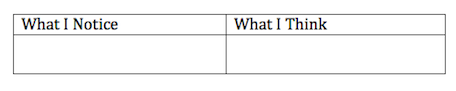

Before we teach our students to know, we need to teach them to notice — particularly if we are filling our curricula with grade-level complex texts. It’s a simple shift. “What do you notice?” I ask, and then “What does that make you think?” On a chart, it can look something like this:

Transformative things happen when we start our teaching with what students notice. Everyone can notice, so there’s that. The classroom suddenly becomes democratic. The back-row boy is now on equal footing with the front-row girl.

What also happens is that noticing grows exponentially: the more you notice, the more you notice. When students begin to realize that they are, first of all, allowed to notice – and second, that what they notice is valid and valued – they begin to notice more deeply and more consistently. This, in turn, helps them “interpret” and “analyze” more successfully.

If we want students to meet the Common Core standards and think in complex ways about complex texts, we need to make sure we are rooting our teaching in what they notice. In that way they truly will become meaning makers rather than meaning takers.