How Do We Select Books Students MUST Read?

This post is adapted from Sarah Tantillo’s new book, Literacy and the Common Core: Recipes for Action (Jossey-Bass, 2014). Sarah is also the author of The Literacy Cookbook (Jossey-Bass, 2012).

In Reading without Limits, Maddie Witter advocates for reading instruction that includes a mixture of shared, guided, and independent-choice reading. I support this approach. Identifying books for the latter two categories is fairly straightforward (albeit dependent on your budget): you need leveled, high-interest books. But how should we select the books that every student must read?

While we want students to fall in love with reading through text choices that excite and interest them, we also need to cover some ground in each grade—skills and content—and ensure that students are adding to their background knowledge base.

When selecting texts that everyone in the class will read—especially at the secondary level—it’s important to expose students to certain classics so that they don’t arrive at college wondering who Shakespeare is. E.D. Hirsch has written extensively about the importance of building cultural literacy and its role in strengthening literacy, period.

In this same vein, my earlier book The Literacy Cookbook explains how prior knowledge drives the comprehension process. It’s a process of accumulation: Reading relies on and builds knowledge, which then improves comprehension, and more reading builds more knowledge and more comprehension.

Text complexity

Another factor that should influence selections is text complexity. The College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Reading speak to this issue very directly with Standard #10 (in the category of “Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity”):

Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently.”

The standards at each grade level specify the grade level or band of text complexity at which students should be reading. For example, in grade 5, Reading Informational Text Standard #10 is: By the end of the year, read and comprehend informational texts, including history/social studies, science, and technical texts, at the high end of the grades 4–5 text complexity band independently and proficiently.

Adams argues for vigilant use of rigorous reading materials, noting that “the challenge … lies in organizing our reading regimens in every subject and every class such that each text bootstraps the language and knowledge that will be needed for the next.”

In other words, you shouldn’t start with the most rigorous texts, but you should organize instruction in ways that ensure your students tackle those most challenging texts in every grade. Adams recommends directly teaching key words and concepts, gradually building students’ knowledge base, and then increasing the depth and complexity of the texts.

Culture and gender

Along with textual rigor, we must also consider cultural and gender-oriented relevance. In The Trouble with Boys, Peg Tyre notes that one reason boys struggle in school is that their elementary school teachers often select texts that boys consider “too girlie,” and when faced with such books, “they decide they don’t like to read.” Indeed, as much as I love the Common Core Standards themselves, I am not wild about all of the suggestions in Appendix B for grade-level appropriate texts.

So, OK, even though some girls might love it, Black Beauty might not be for everybody. But how should you decide which texts to require in your curriculum and which to save for optional or independent reading?

Along with the issue of gender, here is another important angle to consider: What are the demographics in your school? This question raises at least two other questions: (1) How will you entice students with culturally-relevant selections? And (2) How will you widen students’ perspectives through the lenses of diverse texts? It’s not enough to draw students in; we also have to show them the wider world. Discussions around these two questions often sound like conversations about nutrition: How can we achieve a healthy balance?

What about themes and topics?

In addition to contemplating cultural and gender relevance, we must also consider the curriculum’s themes, potential author studies, and a range of genres. Let’s examine these ideas more closely….

• What themes/topics will you address this year—both in your subject and in other content areas? For example, if you’re an English teacher, have you talked with the history and science teachers about interdisciplinary opportunities and appropriate texts to build background knowledge? English teachers should not be the only ones using books in their curriculum.

When we began designing the ninth-grade curriculum at North Star Academy, we decided that in addition to an array of books in English and history, students would also read The Hot Zone by Richard Preston (an engrossing narrative about the Ebola virus) in their biology class.

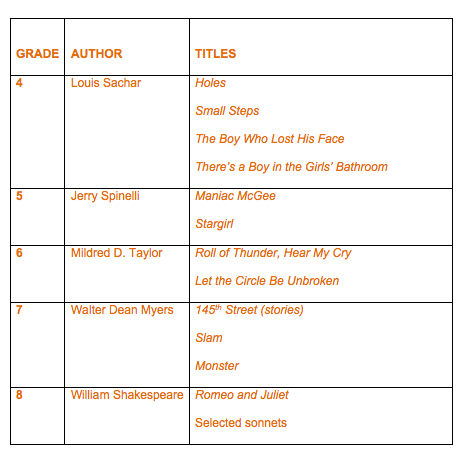

• Which authors have written enough grade-level appropriate books to warrant consideration for potential author studies? One school I worked with made the following choices:

• Which genres do you want/need to address? Look to the Common Core Standards for guidance. The K-12 Reading Informational Text Standards require that we pay persistent attention to nonfiction (and, again, across the curriculum, not just in ELA classes).

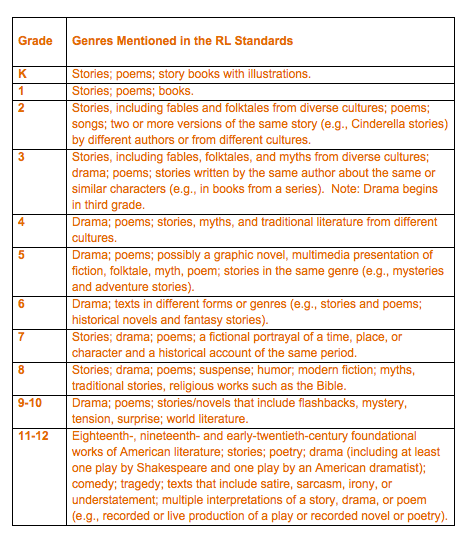

The K-12 Reading Literature Standards consistently mention “stories, poems, and drama,” but they approach them differently in different grades. Here is a quick overview culled from the Standards:

Whatever texts you select, it’s important to remember that your choices will significantly shape student learning.

Rationales like “We’ve always used that book” or “We have 500 copies of it” or “It doesn’t really fit, but the kids like it” are not good-enough reasons to keep a text. Instead, as much as possible, let’s make thoughtful, purposeful decisions about the books we ask all of our students to read.

The language of Black Beauty is somewhat antiquated, and very British, but will students ever feel comfortable reading Frankenstein or Great Expectations if they don’t study simpler British novels? In spite of the girl on the cover, Black Beauty is not about a girl, nor even a female.The narrator is a male horse and most of the characters are men.

Thanks for your comment, Sharon. To be clear, I’m not completely opposed to texts with antiquated language. My point was that Black Beauty might not be everyone’s cup of tea, and more generally, it would have been nice for the list designers to suggest more options. More expansive guidance on grade-appropriate texts would be helpful. In fact, that’s what motivated me to write this piece.

What are your thoughts on Required Summer Reading, Grades 6-12? (1 mandatory book + 2 optional books) All 3 books have assignments/tests/essay/projects that are due Day 1 or Week 1 of school.

Hi, Lulu– Thanks for your excellent question! Whether you’re assigning particular books or giving students a range of choices (or some combination of the two), you undoubtedly want students to demonstrate that they have completed the reading in a way that doesn’t torture them or you.

In far too many schools, I’ve seen assignments that are boring for students and time-consuming for teachers to grade. You don’t want to come back in the fall and start out frustrated and annoyed with your new students, right? Instead of plot summaries (which invite plagiarism) or numerous journal entries (which, in bulk, can undermine the fun of reading) or any number of other options that result in superficial responses (or no responses at all), consider the Character Analysis approach, which is actually useful for follow-up work in the fall.

My TLC Blog entry on summer reading explains how it works and includes a free sample packet for use with middle and high school students. Let me know if you have any other questions. Cheers, ST

The junior high and high schools that I attended did not have any required reading. I was in the “college prep” program in high school. Looking back, I feel I was cheated.

I am really happy to read these web site posts which contain lots

of helpful information, thanks for providing these statistics.