How to Avoid Kidnapping Your Students

Our thanks to Sarah Tantillo for sharing this post, the first of two on “Rigorous, Purposeful, Measurable (RPM) Objectives,” adapted from her new book, Literacy and the Common Core: Recipes for Action (Jossey-Bass, 2014).

By Sarah Tantillo

If you walked into your classroom and told all of your students to stand up, follow you, and get on a bus without telling them where you were going or how long it would take to arrive, they might look at you a little funny. Because that’s called kidnapping.

But the truth is that many teachers do this every day: they walk in and tell their students to do things without explaining what they’re doing or why they’re doing it.

Then they wonder why their students are resistant.

The failure to establish clear objectives

If you fail to explain the rationale for the lesson, in addition to missing an opportunity to engage students from the moment they walk into the classroom, you are also sending this implicit message: “You are my hostage. You must do whatever I say. Trust me.”

That last part is the clincher. Why should anyone trust a kidnapper?

If a student asks you, “Why are we doing this?” you shouldn’t take it as a sign of impudence. It’s a legitimate question. And you need to know the answer. Actually, you need to answer that question even before it gets asked.

Don’t be a kidnapper

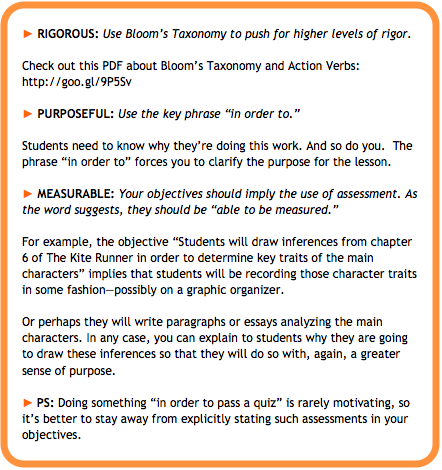

One way to avoid kidnapping your students is to establish, post, and explain your objectives for the class. These objectives should be what I call “RPM”: Rigorous, Purposeful, and Measurable.

Why? Because these objectives represent a meaningful promise, which is: “By the end of this lesson, you will know/be able to do this rigorous thing, and here’s why it’s so important.”

If you keep this promise every day, students will absolutely trust you. And they will learn a lot more than they otherwise would have.

Two caveats:

(1) While it’s crucial to post and “sell” your objectives, it’s a waste of time for students to copy them down. Just make the pitch and keep it moving.

(2) In some inquiry-based lessons, you may want to withhold the objective(s) until students have engaged in some discovery work: that’s OK as long as you give some hints to suggest a sense of direction and reveal the objective(s) later.

Here is a cheat sheet for creating RPM objectives (download):

Here are some examples of RPM objectives:

- Math: Students will be able to (SWBAT) apply knowledge of finding the areas of quadrilaterals, triangles, and circles in order to find the area of irregular figures having missing dimensions.

- English: SWBAT draw inferences about the characters in chapter 1 of _________ [title of book] in order to make predictions about the plot.

- History: SWBAT list and analyze the causes of the Civil War in order to explain what motivated the North and the South to continue fighting in spite of the bloodiness of many battles.

- Science: SWBAT observe and record cloud patterns in order to explain the relationship between cloud formations and the weather.

A few hints about rigor

While it makes a lot of sense to teach with RPM objectives, it can be challenging when you first start to develop them. Let me offer some hints about rigor.

Keep in mind that rigor is not solely a function of a verb’s placement in Bloom’s Taxonomy. For example, although it is true that “explain” is typically a higher-level thinking skill than “describe,” sometimes asking students to “describe” can be quite rigorous—particularly when the description requires significant background knowledge.

If “describe” is used to “describe what you see” or “describe how you feel,” it’s not too difficult. But take a look at this objective:

If you don’t know what an “economy” is or what “features of an economy” are—much less what they were in the pre-Civil War South—you will have a tough time meeting this objective. The requirement for content knowledge adds rigor.

Moreover, the stated purpose—“to explain…”—amplifies the rigor in this case. That’s another thing: pay attention to the verb used to state the purpose: it can expand or deflate the overall rigor. Notice the difference between doing something “in order to evaluate…” vs. doing something “in order to list….” With the word “list,” you can almost feel the air rushing out of the room.

And while we’re on the subject of verbs, unless you are psychic and can read your students’ minds, the verb “understand” should never appear in your objectives. It’s not rigorous because we can’t tell if it’s been met.

Rigor includes text complexity

In the Reading Standards for Literature and for Informational Text, Standard #10[4] deals with text complexity and ensuring that students read grade-level appropriate texts. As noted in a previous post, text selection is a key variable in curriculum development, and accordingly, it affects the rigor of objectives, lesson plans, and instruction. Bottom line: Pay careful attention to the texts that your objectives are based on.

Put the correct spin on your lessons

Use these ideas, tools and RPM strategies and you’ll kidnap-proof your classroom and assure that both you and your students know where you are going — and why you want to get there.

__________

Sarah consults with schools on literacy instruction, curriculum development, data-driven instruction, and school culture-building. She has taught high school English and Humanities in both suburban and urban public schools, including the high-performing North Star Academy Charter School of Newark. Visit her resources website.

It’s not kidnapping. It’s called trusting a person in a position of authority. The truth is learning targets are more about making it easy for administrators to assess whether or not teachers are covering curriculum.

PS….Students at the high school level are motivated by getting good grades.