How Teachers Can Restore Our Students’ Right to Wonder

by Nanci Werner-Burke

by Nanci Werner-Burke

Is education truly a creativity-killing machine?

In his widely-distributed video presentation Changing Education Paradigms – frequently shown at inservice days – Sir Kenneth Robinson posits that schools are built on industrial models.

Similarly, Laura Robb, a well-respected researcher and author in literacy studies, confirms (here at MiddleWeb, in October 2014) what Newsweek had asserted in 2010, that we are in a “national creativity crisis.” Robb calls for a systemic attack on poverty and increased support for teachers as a means to address this issue.

Both authors cite studies documenting decreasing scores on measures of creativity in children as they progress through the schooling process.

While it is hard to argue with the line of thought developed and the evidence presented in each author’s work, it is still harder to immediately realize what each of us might be able to do in our own classrooms to get the creativity ball rolling (or rolling faster) and also balance curricular demands and instructional best practices (without it all spinning out of control).

Restoring the Right to Wonder

Questioning is a practice that presents strong potential for the type of change we need to promote creativity and maintain engagement. The 2010 Newsweek article on the creativity crisis notes that,

Preschool children, on average, ask their parents about 100 questions a day…by middle school they’ve pretty much stopped asking. It’s no coincidence that this same time is when student motivation and engagement plummet. They didn’t stop asking questions because they lost interest: it’s the other way around. They lost interest because they stopped asking questions.”

Consider this trend in the context of research by Tienken, Goldberg, and Di Rocco (2009) that the average teacher asks about 100 questions per day, and the shift in the communication pattern is clear.

This cognitive disconnect morphs into an affective one, resulting in that noted drop in engagement and motivation.

How can we reverse this pattern and help our students to stay in the learning game? One way is to open the door for a classroom that is more social in design. We can also structure our time so that students can practice the deeper learning skills – the ability to work collaboratively, think critically and to identify and solve authentic problems, and also communicate effectively.

But this assertion is still too general and sweeping in terms of actual classroom practice. Fortunately, we may already have in our professional toolkits a specific and concrete framework for affecting immediate change: Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Helping Students Bloom

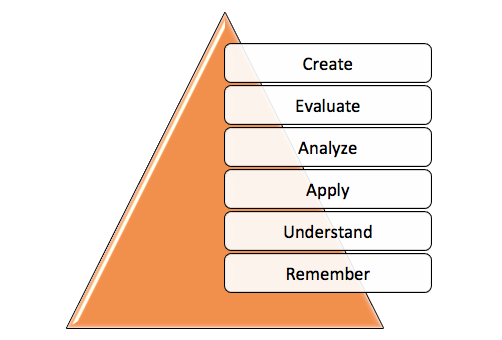

During formal preparation for the teaching profession, almost every teacher is exposed at some point to Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (1956), which delineates learning tasks in terms of their cognitive, affective, and psychomotor complexity. Although the number is growing, fewer teachers are aware of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, published by Anderson and Krathwohl in 2001, which maintains some of original language and categories but more heavily emphasizes the act of creating, of “putting elements together to form a novel, coherent whole or make an original product” as most complex of cognitive functions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Categories of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, arranged bottom to top, from the most basic to complex

According to David Kraftwohl, (in Educational Psychologist, 45(1), 64–65, 2010) who worked on both versions, the original Taxonomy was designed “to be a framework for studying, understanding, and solving educational problems,” and the revised version was updated to better “help teachers understand their craft and to work continually to improve their practice.”

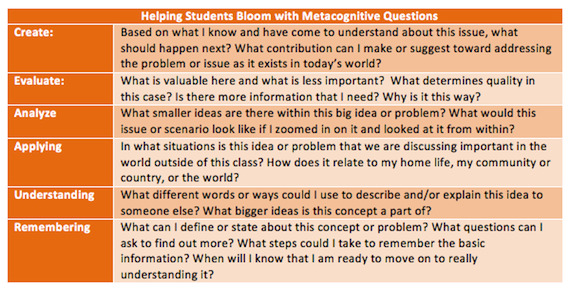

Bloom’s Taxonomy became the core of teachers’ questioning practices. It provided a common language and way of thinking for educators; our original common core. What if the revised version were used as a core for maintaining and refining student questioning practices? What if we involved students meta-cognitively in their own learning, empowering them to solve problems relating to their own educational practices of thinking and learning?

Bellanca and Brandt (2009) note that technology has spurred a shift in our society by placing exponential amounts of information at our fingertips and the ability to communicate and build ideas across geographical distances. Their work on 21st century literacy calls for shifts in education to keep pace, to change from old-style instruction that emphasizes manipulating predigested information to build fluency with routine (canned) problem-solving to a new style where learners filter data from experiences in complex settings to develop skills in sophisticated, real-world problem-solving. The new Bloom’s has the potential to serve as this filter.

Picture a middle school classroom where part of the activities focus on how the participants might use a student-centered version of the new Bloom’s to self-regulate their learning as they navigate sources and discuss ideas (Figure 2).

Using Blooms-based Questioning with Students

Students who participate in actively using these terms to understand their own level of knowledge and understanding are effectively sharing the framework of their teacher and bringing what has long been a staple of the educational process to bear in maintaining their engagement in thinking and learning.

Bloom’s Taxonomy and its accompanying verbs are woven into the fabric of teaching. Empowering our students to weave Bloom’s skillfully into their own learning is a process that will jumpstart questioning and result in our education model transforming into a richer, collaborative tapestry.

We’ve been reading a post at Grant Wiggins’ blog this morning, reporting on results from a survey of 5th graders. Here’s an interesting table. You can read more by clicking here.