Grammar Really Matters in a Community of Writers

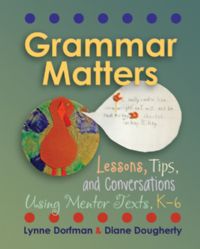

In their book Grammar Matters: Lessons, Tips & Conversations Using Mentor Texts, Lynne Dorfman and Diane Dougherty identify an overarching goal: to help students come to “view grammar as something to appreciate, enjoy, and even admire” as they grasp the power that comes from wielding punctuation and grammatical rules in ways that assure their messages “will be communicated and understood” and “make a lasting impression on their readers.”

The best way to accomplish this, Dougherty and Dorfman believe, is by teaching the “Conventions of Standard English” (CCSS) seamlessly within the writing workshop model, avoiding worksheets and rote lessons that will never “make someone a lover of words or a better speaker and writer.”

This article, adapted with permission from Grammar Matters (Stenhouse 2014), focuses on the authors’ ideas about building a classroom writing community where this natural integration can take place. (Read Linda Biondi’s book review here.)

by Lynne Dorfman & Diane Dougherty

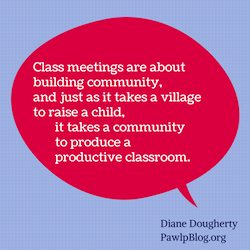

Successful writing workshop classrooms rely on a number of factors. These include, of course, sufficient time, choice of topic, and constructive feedback. Equally important, however, is the establishment of a writing community— a safe environment in which students and teacher share their struggles with writing, experiment with possibilities, and take risks knowing that their efforts are valued.

This environment does not occur by magic, nor is it established in one day or one week; community building is continuous. The wise writing teacher makes community building a priority throughout the year. Each school year should be a new beginning for everyone, teachers included. How we begin that year and how we nurture our students throughout the year are the scaffolds upon which we build success for all.

What we mean by “building community”

What exactly is meant by “building community”? Community building is not team building; it’s not fun and games; it’s not boosting self-esteem. Although there are elements of all of these in a good community-building activity, the primary purpose of community building is education: students in a nurturing writing community have a better chance of becoming committed readers and writers than those who do not have that advantage.

Anyone with access to a computer and the Internet can find multiple beginning-of-the-year exercises for students and teachers, and we voice no opposition to teachers using them. Our objections lie in the use of team building only during the first week or two of school and the attitude that this one week is all it takes to build a learning community. Nothing could be further from the truth. Community building needs to be ongoing; it needs to be embedded in every action—from greeting students at the door each day to making an effort to know each child individually.

Some community-building ideas

How lucky we are to be writing teachers! When we read and respond to student writing, we learn a great deal about our students—information that can easily get lost in the everyday march to cover the curriculum. How we encourage students to write and share begins on the very first class meeting and continues each day thereafter.

Here are a few community-building activities that have proven successful for the writers in Lynne’s and Diane’s workshops.

✻ Quick Facts

A writing classroom supposes that students will write—that they will explore multiple topics and genres, confer about their writing, and revise and edit their pieces. Ask each student to jot six to ten facts about themselves, including one plausible lie. Share your own facts/lie with the class.

Diane Dougherty

• I am a good cook.

• I once won a contest for baking the best apple pie.

• I have three grown children and eight grandchildren. I have been married for 48 years.

• I have never lived outside of the state of Pennsylvania.

• One of my favorite pastimes is reading the Sunday New York Times and doing the Sunday crossword puzzle.

As students read their lists, ask the class to try to determine which of the “facts” is the lie. Students enjoy trying to guess correctly, but the real purpose of the activity is to help students to grow their lists of topics for writing. You can expand this activity by asking students to write a paragraph developing content about one of the truths and another developing content about the lie. These can be shared or used as examples for conferring later.

✻ Poetry Scaffold

Another surefire community-building activity uses a poetry scaffold (with embedded grammar!) encouraging student participation. Ask students to form pairs. If there is an odd number of students, the teacher partners with a student to make an even number.

Lynne Dorfman

Students interview each other, asking questions about hobbies, likes and dislikes, favorite places, and so on. For some classes it may be beneficial, or even necessary, to brainstorm a list of questions for this activity.

Encourage students to take notes about what their partner tells them. After the interviews are completed, ask students to write poems about their partners using the following scaffold:

Line 1. Two adjectives connected by “and”

Line 2. A verb (activity or sport is optional) followed by an adverb

Line 3. A simile starting with “As ______ as . . .”

Line 4. If-only statement

Here are some student examples:

Geoffrey: Intuitive and observant, Plays soccer skillfully As bright as a cardinal on a wintry day If only I could be as enthusiastic as Sean.

Jamal: Comical and thoughtful, Paints pictures beautifully, As funny as a carload of clowns If only I could be as witty as Jessica.

Garcia: Giving and friendly, Ice skates smoothly, As fast as a penguin on ice, If only I could be as athletic as Timmy.

Depending on your grade level, you can adjust the instructions to focus on verbs and adjectives only or omit a step such as the simile or if-only statement. This activity could follow a mini-lesson on adjectives within your reading workshop when you might create an anchor chart of character traits.

Additionally, students can continue to partner with their classmates to write more poetry using this scaffold. Post their poems around the room in the beginning of the year so students can read about their peers and get to know one another.

Sustaining your writing community

Our writing workshops have changed from year to year, depending on a number of factors. While the basic framework stays the same, with focus lessons, guided practice, writing time, and sharing, how we organize the classroom and how we deliver instruction may vary according to our students’ needs.

Don’t expect that your writing workshop will look the same every day or even from year to year. What should not change, however, is time for sharing because sharing writing and taking risks with writing are both ways that our student writers gain confidence and become better writers.

Unless we have fostered a community of learners, students will be hesitant to read their pieces to the class, and their classmates will be unwilling to offer praise or suggestions.”

Furthermore, sharing helps writers recognize problem-solving strategies they and their fellow writers are using. When Braden shares how he revised his piece of writing for sentence variety, for example, and explains why he did it, his classmates see a strategy that they can appropriate as their own.

Errors can be gems

It’s one thing to have a conference with the teacher; it’s another to know that, as a writer, you have the entire class with whom to confer and to problem-solve.

Michael Smith and Jeffrey Wilhelm tell us that “all significant learning requires risk taking and mistake making.” As students are challenged by new genres, formats, organizational patterns, and sentence structures, they are probably going to make errors. During conferences, teachers must decide which errors should be addressed. In order to do this, teachers need to know what their students (sometimes on an individual basis) are ready to learn, understand, and apply.

Often, the focus is on an error that is repeated frequently and by a significant number of the students in the class. When an error diminishes the readers’ understanding of the text, the error should be addressed.

Other errors take away from the author’s voice of authority. If, for example, the student is writing about a famous person such as Abraham Lincoln and misspells that person’s name, the writer will not be seen as an expert in the minds of the readers, regardless of the quality of the content.

Building community during share time

In whole-group or small-group conferences, the teacher and the students are given the opportunity to offer praise first and suggest refinement or polish second. Here are some ways to make good use of share time in writing workshop and sustain your writing community:

► Take a quick survey. Popcorn around the room: students read a line of their piece when they’re ready to, in no particular order. Choose a student to be first, and then have students continue to share aloud the one line they really loved from the piece they are currently working on (almost all students will participate, as well as the teacher).

► Ask students to perform collaborative pieces in reader’s theater format or another interesting way (possibly use background music or create backdrops or props).

► Use share time to conduct a group conference using praise-ponder-polish. Share snippets from your own writer’s notebook and ask the students to share from their notebooks.

► Build in time for students to turn and talk with a partner about something they struggled with today—something that was difficult for them to do.

► Ask students to share something that a peer or peers had tried out that they would like to try, too.

► Suggest to your students that they find one word from their draft that they consider to be a “gem” and share it aloud (works well when everyone does this and you can collect on a poster that you pass around to be displayed).

► Students share something about their writing that surprised them!

► Ask students to share the most important sentence in their piece. Ask, “Why did you choose it?”

► Students share the emotion that drives this piece. Ask, “What were you feeling when you decided to write?”

In community, young writers teach each other

Students don’t have only one writing teacher; they come to recognize how their own classmates may be experts. When Matthew wants to know something about hockey rules, he knows he can ask Bryce. When Jada wants to know if her description of the waterfall in the hotel’s pool works, she can ask Gia to listen to it, and Jada knows she will get specific feedback.

How does all this happen? Only by building community! Don’t neglect this important factor.

Download Lynne and Diane’s Top Ten Tips for a Teacher of Writers

_____

Diane Esolen Dougherty lives with her husband in Downingtown, Pennsylvania. She is a graduate of West Chester University and received a Master of Arts degree from Villanova University. Diane was a classroom teacher for 32 years as well as head of English/Language Arts for 10 years and is active in state and national Writing Project initiatives.