Talking about Terror with Middle Schoolers

A MiddleWeb Blog

Some mornings when I read the paper, all I want is The Daily Show.

Some mornings when I read the paper, all I want is The Daily Show.

The eighth graders in my U.S. history classes cannot avoid the news. I do not want them to avoid the news. Each day, we start class by discussing a current event. Each Thursday night, they find an article to share.

Yet some mornings it harrows us to talk about world affairs, especially when acts of terror occupy the stage.

Humor in the classroom, even dark humor about difficult topics, can press a much-needed reset button, offer a way for us to step back and talk about an issue.

This year, one of Jon Stewart’s more appropriate and nonpartisan clips clarified class discussion about ISIS drone strikes, and the Saturday Night Live send-up of Obama’s immigration executive order enlivened our Constitution unit.

When comedy fails

But sometimes humor doesn’t work. This year, for both the Eric Garner grand jury decision in December and the Charlie Hebdo magazine massacre in January, even Stewart dropped the jokes.

For the Garner case, he chose anger and confusion: “If comedy is tragedy plus time, I need more…time.”

“Our goal tonight,” Stewart continued, “is not to make sense of this, because there is no sense to be made of this. Our goal, as it is always, is to keep going.”

I agree.

But many mornings with middle schoolers, I’d like more than merely survival.

Grappling for hope

How can we achieve some sort of daily optimistic grappling with world events?

The week of the Charlie Hebdo murders we followed the story Wednesday, Thursday and Friday in class. The shootings brought together so many historical and current themes: immigration, freedom of speech, terrorism, religion.

The students knew about the events from their parents and especially from the “Je Suis Charlie” iconography lighting up Instagram and Tumblr. They kept raising questions: Why would someone do this? What is a jihadist? How important are political cartoons in Europe?

Once we had established the outline of events, though not in any ugly detail, I wanted to wrest my students, and me, out of the sinkhole I felt we were in.

Humor was out. Maybe a more serious approach would work.

“This morning as I read the news, I was devastated,” I said. “But I don’t want to stay that way. So how do we, how do you, move from despair to action?”

At first they focused on actions of comfort: eating good food, playing video games, texting a friend and then getting into a conversation about something totally different.

“That’s fine, but it’s all essentially distraction,” I said. “What about moving from despair to action while you are still focusing on the news?”

This was harder. A few kids suggested we restrict the terrorists to certain countries. (This had also been a possible class solution to the Ebola crisis.) The always-suggested idea of bombing the terrorists came up.

Preparing for the future through actions today

One student mentioned that he is heartened by knowing his generation will tackle these issues as they grow up. Me too. And talking in community helps.

- Write an op-ed that gives an anti-terrorism plan.

- Analyze a page of Senate Foreign Relations Committee testimony on nuclear negotiations.

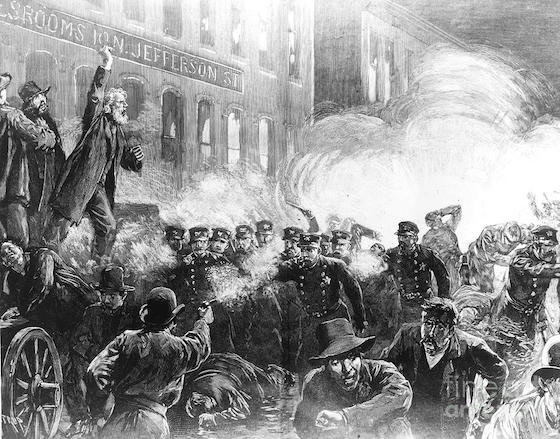

- Study acts of violence in history, such as the 1886 Haymarket Square Riot, and pretend it is your responsibility to bring together both sides as a mediator.

- Create a Prezi showing how First Amendment cases over the years have solidified freedom of the press.

The list goes on.

But I also want students to gain tools to deal with news in the moment, tools that have nothing to do with a teacher’s assignment and everything to do with our connection to other people.

The jury is still out on the best way to do this.

How do we as adults cope, after all? Talk, discuss, once in a while protest, wring our hands, talk some more, read articles, share videos with friends, vote for people we think will help, occasionally run for office ourselves, and ultimately just try to get a good night’s sleep.

I guess I hope my students will be better at this than we are – will do a better job of addressing the world’s problems.

Team Civilization

I would like these eighth graders to appreciate our own country’s strengths, to remember, as Jon Stewart observed after Charlie Hebdo, “that for the most part the legislators and journalists and institutions that we jab and ridicule are not in any way the enemy.

“For, however frustrating or outraged the back-and-forth can become, it’s still back-and-forth conversation of those on, let’s call it, ‘Team Civilization.’”

Team Civilization. It’s a start, anyway.