How Our Mock Trial Improved Argument Writing

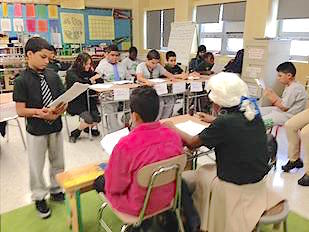

A few months ago I facilitated my first mock trial in my sixth grade ELA classes. It followed our close reading of Chew On This: Everything You Don’t Want to Know about Fast Food, an adaptation of the book Fast Food Nation for younger readers.

Having never facilitated a mock trial before (or participated in one when I was growing up), I was extremely nervous about how it would unfold. Aside from the gavel and wig for the judge, I wasn’t sure the kids would buy into a courtroom experience.

An activity like this represented not only a significant investment of scarce classroom time, but it required me to shift a fair amount of control to my students. I believe in empowering them, but we all feel more comfortable if we can predict what will happen.

Of course every teacher feels this way when we are about to take a risk in our classrooms. I’m happy to report that this risk paid off – students and teacher were well-behaved and learned a lot.

The inspiration for our mock trail was Pelman vs. McDonald’s, a 2003 lawsuit alleging that food from McDonald’s restaurants was responsible for making people obese. The suit was actually brought by a group of overweight children in New York City, two facts that heightened the interest of my NYC middle schoolers considerably.

Here’s what I’ve learned, in my first attempt, about the instructional benefits of a mock trial.

Dramatic readings are a perfect way to build more fluent readers

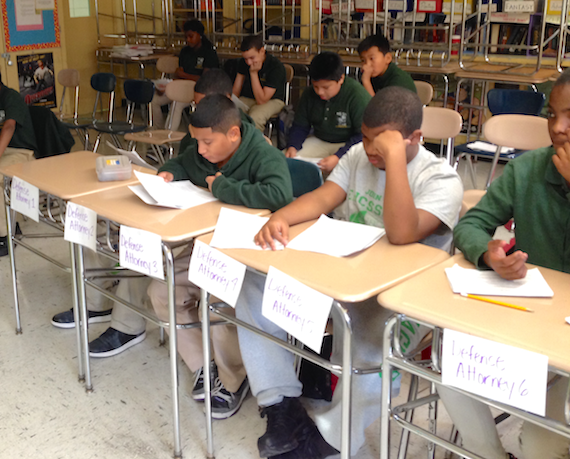

I assigned roles and gave my students their scripts to go home and practice over the weekend. There were some longer parts, some shorter parts, and then there were the jury members who didn’t have any lines to prepare (more on that later). What was amazing about this was the built-in differentiation for each role.

- I have one beginning language learner and he made the perfect bailiff! His lines were simple, repetitive and routine. It helped him to build confidence and vocabulary quickly.

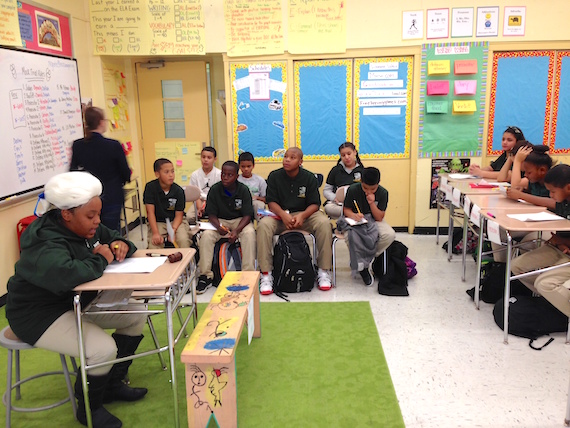

- The lawyers (both the prosecution and the defense) showed tremendous growth in varying their intonation to engage the audience. After all, they needed to be as persuasive as possible to convince the jury.

- The judge had to model facilitation skills and sometimes think on his/her feet to quickly respond to an unruly courtroom.

- Then there were the witnesses who had to do a tremendous amount of character analysis in order to embellish their performance and capture their character’s true personality. These students generated amazing questions such as, “Mrs. Grate, is this character trustworthy?” Or, “Should I play her like a shady character?” I mean talk about reading between the lines and strengthening inferencing skills!

The mock trial motivated them to learn new vocabulary quickly

Suddenly long, complicated words meant something to my students. They needed to know what “objection!” and “overruled” mean. Was “sustained” a good thing? If so, what did it mean?

Concepts of consumer fraud and manipulation took center stage because they wanted to understand what they were arguing, so they could win. It wasn’t enough just to know what the words on the page meant, though. It led to a deeper understanding of formal language versus informal language.

The concept of code switching, a vital skill for most children to learn, and especially for urban children, naturally arose from this experience. Several students were quick to note that there were no slang words in the text and quick to question why. That led to a rich discussion, which resulted in them drawing connections between code switching in a courtroom and code switching in the classroom.

This life lesson moved them forward toward more than being “college ready”, it made them more ready for the professional world I hope they will enter one day.

The mock trial built on their knowledge of our legal system

As crazy as it may sound, several of my students shared that before this experience they thought they wanted to be a lawyer – but they really had no idea what a lawyer actually did.

The mock trial gave them the opportunity to ask questions regarding our legal system and how it functions. They were curious as to why the jury made the decision rather than the judge, and they desperately wanted to know what the function of the bailiff was.

Perhaps the most burning question they had was: Why weren’t the jurors able to ask witnesses questions directly themselves? It lead to a deep discussion as to why the jury couldn’t just pick the side they liked best. They really struggled with the concept of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt.” They were fascinated and wanted to know more.

Students were absent or unprepared could participate in a meaningful way

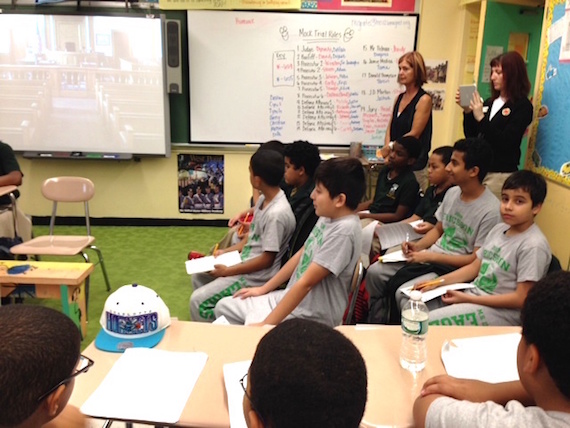

That’s another place where the jury comes into play. If a student was absent during the run-up to the mock trial, they could come in and instantly have a role and actively participate. The jury members take notes, and at times, ask the judge to have a witness repeat their testimony.

They then are responsible to leave the room and deliberate, debate and ultimately come to a unanimous verdict. The debates that took place in the smaller groups were intense. Some students realized that their notes weren’t sufficient enough, and they summoned the judge to read back part of the transcript.

Other students were holding their fellow jury members accountable to explain thoroughly how they were justifying their verdict. Every child, despite his or her reading level, was able to take part.

This simulation was the perfect segue into writing our first argumentative essay

Our mock trial followed our close reading of Chew On This and preceded the writing of argumentative essays. Our essay topic: “Should McDonald’s be held responsible for their consumers’ health problems?” The trial activity laid the groundwork beautifully.

Their experiences provided plenty of background understanding and also analogies I could refer back to throughout the writing process. We compared writers to lawyers and examined what strategies the best lawyers use to persuade the jury to side with them. These same concepts were then applied to their writing.

The comparison illuminated the relationship between writing and speaking skills, the author’s craft and word selection. It also illustrated the payoff for selecting attention-getting examples and using persuasive language to drive home a point.

Thoughts and reflections

I was particularly amazed to see the level of questioning and the engagement students had with the various texts. Any middle school teacher can tell you that one of the most difficult things to do is to get struggling readers to read through the same text multiple times. This did the trick.

My students were willing to stick with difficult content and grapple with the text to make meaning of it because it mattered to them. They realized that each time they read it through, they were better able to see how to bring life to their character and their role.

Some how-to tips for other teachers

Interested in implementing a mock trial in your classroom? Here are the steps I took to make it happen:

► I started by looking up an actual case related to the topic we were studying. In this instance I found Pelman vs. McDonald’s. It’s not hard to find interesting cases with your search engine.

► Then I did a little reading on the case. Nothing major. You can just get the basic gist and background information: who was involved and what the verdict was. In Pelman vs. McDonald’s, there was no actual verdict because the judge rendered it a “frivolous lawsuit” and threw it out before it was able to go to trial. I still chose to use it because I knew it was a topic that would connect with the kids, and I took some creative liberties in my scriptwriting.

► After I selected this raw script, I then just went back and rewrote parts of it to fit my needs. Is it perfect? No. But it did the job for our first time around. (See the link to my script below.)

► At this point, you can decide how you want to roll things out. You can pass out scripts, do a class read-through before or a cold reading. Depending upon your needs, you can differentiate any way you see fit.

You can download my script and PowerPoint presentation (I apologize if there are any typos). Feel free to adapt it if you would like. If you try it out, give me some feedback as to how it worked. (For an interesting analysis of the case, see this 2003 article in the journal Health Affairs.)

And if you’ve already done a mock trial, please share a lesson you learned in the comments below!

Mackenzie Grate has been a Title One middle school ELA teacher leader in New York City for the past 8 years. She has a BA in English Education and an MS in TESOL from New York University. She is currently earning her MA in Educational Leadership from The College of Saint Rose. Her hope is to one day open a school with her colleagues based on a collaborative teacher leadership model. Follow her on Twitter @ThisTeacherSays or read her musings about all things educational on her blog at MackenzieGrate.com. She goes by “Mack.”

BIO UPDATE (11/27/19)

Mackenzie Grate is assistant principal at Highland Park Community School in Brooklyn, New York. She has been a middle school educator for the past 11 years in New York City. Graduating from New York University with a master’s degree in English Education and TESOL, she is extremely passionate about restoring and creating more engaging literacy opportunities within urban middle school curricula. When not in school she can be found snuggling her two pugs and reading a good book. (Source)

I am student teaching this semester, and my cooperating teacher (7th grade ELA) and I are doing a mock murder trial in relation to a fictional novel, True Confessions. This article finding its way to my fingertips is beyond perfect timing! We both are eager for our one day trial that puts the main character on trial before the actual trial in the novel. Your article has give me more perspective on how this activity can enhance student learning. We’ve been working on creating arguments along with in depth analysis of various literary works. I can see how this activity will play on previous learning and help with future lessons. I know I’m excited for this activity because I have a lot of knowledge on how a trial takes shape, proceeds, and wraps up. Thank you for the resources you’ve provided, and I will be sharing this with my cooperating teacher!

I was so pleased to see that mock trials have worked for you in your classroom and have been successful in meeting multiple standards! I am a history/social science methods professor and I am creating project-based units that include mock trials based on literature, current events, actual cases, and historical events ~ with many of your same goals! The program, Literacy and the Law: Mock Trials to Meet the Common Core has an advisory team of law professionals who are reviewing the work (as much of it is designed to understand the judicial branch as it relates to democracy). Three cheers to you for your success and thank you so much for sharing ~ you made my day! Keep an eye out for our website – in development stages!

It’s really interesting how you said that kids had an increased level of questions and engagement depending on what text they were using in the mock trial. This seems like it would be a great way to teach kids history or help them understand argumentative writing better. Giving them real-life experience of what those papers could be used for would seem to help them create different connections that would improve their skills and abilities.

Hi, I have run a mock trial. We placed Goldilocks on trial, brought about by the three bears. We started with a mini book club, where a group of 10 or so read the story (same book). Then we looked at how each character would feel during each part of the story – we used inference to fill in gaps (what were her parents like? How far was the cave? What else was in the cave?) using evidence or clues from the text. This helped to provide context of the situation or intent of each participant in the process. I then read the story to the whole class and from there we set up the roles for students and assigned expectations during the process of each factor eg: lawyers, jury, judge, audience etc.