How Dialogue Circles Promote Student Growth

by David Palank

by David Palank

My wife has been touting the positive effects of student dialogue circles for years. She is a middle school teacher and has seen how using this simple technique can result in a significant reduction in behavior infractions.

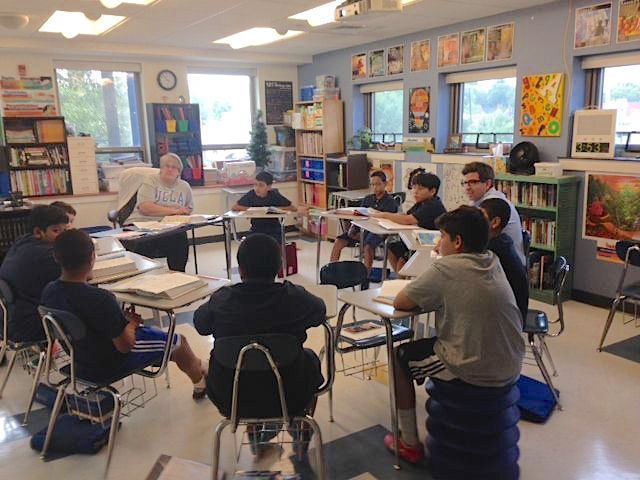

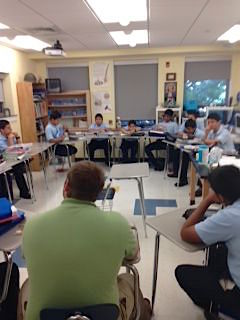

This year we implemented Monday circles into our morning routine at inner-city San Miguel School in Washington DC, where I am principal. Over 95% of the boys at our non-tuition Catholic middle school qualify for free/reduced meals and over 97% graduate from high school.

We picked Mondays because our students can have difficulty “unpacking” from the weekend. They have an issue switching from their hectic home environment to our relatively stable environment at school.

As I researched more about dialogue circles, I found that scientific evidence supports the concept as a powerful tool for improving multiple aspects of a school climate.

The Power of the Circle

These circles are so powerful because they facilitate the release of the hormones oxytocin and dopamine in the brain.

Oxytocin and human bonding

Oxytocin has been known by many names recently – the moral molecule, the herding hormone, the cuddle hormone and more. It is a relatively new discovery in science, but the power of oxytocin for facilitating interpersonal cooperation is far reaching.

It is involved in multiple human bonding behaviors including childbirth, trust (2), generosity, and willingness to share one’s emotions in a social setting, and is released through touch (3). It also motivates us to work together for a common purpose, according to researcher Paul Zak, author of The Moral Molecule and founding director of the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies at Claremont Graduate University:

“Oxytocin helps us respond appropriately to our social environment by changing its amounts in the brain second by second… (the) question is how can one increase their level of oxytocin when interacting with others and thereby increase empathy and compassion towards them” (4).

Ways to increase oxytocin levels

There are other ways to increase oxytocin levels, but the following are the most practical ways to do so in the classroom.

Human contact will increase oxytocin levels. A simple handshake before entering the dialogue circle will increase oxytocin levels.

Eye contact will also increase oxytocin levels. Circles are great for maintaining eye contact and therefore facilitate more trust in the group.

Trust building in Dialogue Circles

When they feel trusted, students will be more willing to share their ideas and troubles. Engaging in self-disclosure will raise the perceived level of social connection, which will in turn raise their levels of intrinsic motivation. People in studies have actually given up money to talk about themselves, as researchers Diana Tamir and Jason Mitchell explain:

“Intriguingly, findings also suggested that both parts of ‘self-disclosure’ have reward value. Although participants were willing to forgo money merely to introspect about the self, and doing so was sufficient to engage brain regions associated with the rewarding outcomes, these effects were magnified by knowledge that one’s thoughts would be communicated to another person, suggesting that individuals find opportunities to disclose their own thoughts to others to be especially rewarding” (6).

Self-disclosure creates an environment where students feel socially connected. Social connection not only helps students to feel better about their situation, but can also increase intrinsic motivation.

The benefits of social connection

A variety of benefits associated with making social connections can be facilitated in a Dialogue Circle:

► Persistence

Students in studies who felt socially connected persisted 48–64% longer on a challenging task, reported greater interest in the task, required less self-regulatory resources to persist on it, became more engrossed in the task and performed better on it. They also expressed greater enjoyment of and interest in the task than participants in control conditions (7).

► Increases Grades

Social belonging helped raise grades in African-American students. One intervention allowed first year college students to learn that all students worry at first if they belong in college but over the years everyone comes to feel at home. African-American students that were involved in the experiment earned higher grades during the next 3 years and also reported better health than the control group (8).

This intervention helped students attribute daily struggles to difficulties that occur with transition, instead of believing it meant that they did not belong. The most interesting part was that when polled about the experiment years later, most did not even remember the intervention, just the message. The intervention became an inner dialogue that the students took ownership of instead of an outside intervention.

► Positive cross cultural interactions

Social connection through cross-group friendship can eliminate or reduce negative expectations about intergroup interactions. During three sessions, Latino and White duos exchanged self-disclosing information through questioning. An example of one of these questions was “Who is the most important person in your life?” They also completed cooperative activities.

Participants in the study initiated more intergroup interactions during a three-week diary period after becoming friends with a cross-group individual. Participants who had made a cross-group friend reported lower anxious mood during the diary period as well (9).

A Dialogue Circle process

2. A talking piece (some easily held physical object) is used, and only the participant with the talking piece may speak. A participant may choose to pass; the facilitator may tell the participant that they are expected to share later.

3. Participants set their own ground rules prior to starting the circle.

4. Participants build community and trust. The facilitator states this purpose when going over the ground rules.

5. To achieve initial comfort among participants in the dialogue circle, facilitators might offer questions or prompts like: If you could choose one super power, what would it be and why? or Describe your safe/happy place.

(See this Edutopia video/article about K-5 circles)

Dialogue Circles as instructional tools

Participants can build rich discussions around topics in the dialogue circle, where they have the opportunity to be exposed to different perspectives. Some examples for the classroom:

- In ELA class, students share how they relate to a particular character in a story under study.

- In history class, they talk about how they relate to a particular person in history.

- In guidance situations, they talk about how a particular incident was handled.

- In math class, they explore different ways to solve a math problem.

- In science class, students can predict what will happen in a lab experiment.

Dialogue circles are simple to organize and activate. They are versatile tools that can increase engagement in any lesson, become part of a good classroom management plan, and help students who have many challenges in their lives develop more resilience, empathy and hope for the future.

David Palank (@PalankSMDC) is principal of San Miguel School in Washington, DC and blogs at Class Hacker. He has taught or worked as principal at San Miguel for eight years and has a Master’s in Supervision and Administration from Marymount University. This article is adapted from his upcoming book, tentatively titled Class Hacker: Working Smarter not Harder to Learn, Teach, and Lead.

Classroom images: San Miguel School

_____

(1) http://www.dialogue-circles.com/ Also see: A slideshare describing the Dialogue Circle Method.

(2) Baumgartner T., Heinrichs M., Vonlanthen A., Fischbacher U., Fehr E. (May 2008). “Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans.” Neuron 58 (4): 639–50.

(3) Lane A., Luminet O., Rimé B., Gross J.J., de Timary P., Mikolajczak M. (2013). “Oxytocin increases willingness to socially share one’s emotions.” Int J Psychol 48 (4): 676–81.

(4) Zak, P. (2013, November 7). The Top 10 Ways to Boost Good Feelings Lab-tested methods to raise oxytocin, and feel better about yourself and others. Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-moral-molecule/201311/the-top-10-ways-boost-good-feelings

(5) Zak, P. (2013, December 17). How Stories Change the Brain. Retrieved January 13, 2015, from http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

(6) Tamir, D., & Mitchell, J. (2012). Disclosing information about the self is intrinsically rewarding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(21), 8038-8043.

(7) Butler, L., & Walton, G. (2013). The opportunity to collaborate increases preschoolers’ motivation for challenging tasks. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 953-961.

(8) Blackwell, L. A., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Theories of intelligence and achievement across the junior high school transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78, 246–263.

(9) Page-Gould, E., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). With a little help from my cross-group friend: Reducing anxiety in intergroup contexts through cross-group friendship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1080–1094.