Choose Your History Teaching Adventure

A MiddleWeb Blog

Engaging With History in the Classroom, a 2014 Prufrock Press series by Janice Robbins and Carol Tieso, examines American history through multiple perspectives. It utilizes a number of pedagogical strategies like structured academic conversations, specific reading comprehension and annotation tools, and provides resources including primary sources, helpful maps, and timelines.

Engaging With History in the Classroom, a 2014 Prufrock Press series by Janice Robbins and Carol Tieso, examines American history through multiple perspectives. It utilizes a number of pedagogical strategies like structured academic conversations, specific reading comprehension and annotation tools, and provides resources including primary sources, helpful maps, and timelines.

Everything is included in an attempt to raise the level of discourse in the history classroom as well as to move curricula in line with Common Core Standards for the middle grades.

The series consists of four books. Each is essentially its own unit with all accompanying materials and instructions: the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, the Post-Reconstruction Era, and the Civil Rights Movement.

While it can be, and likely is intended to be, taken as a whole curriculum for a U.S. History class, it can also be used (similarly to the SHEG resources from Stanford) as stand-alone lessons. Teachers who are required by districts or administration to teach from a particular series or curriculum can use parts of these units to augment what they already have.

For a new teacher without any curriculum options at his or her disposal, this is an incredibly rich resource. For a teacher with an existing curriculum, it is useful as well — one in which the teacher can “choose their own adventure,” picking from some well-thought-out course material, deciding what offerings best supplement their current content in the classroom and what suits their teaching style and objectives.

The Hook: Grounding History Chronologically and Geographically

Each unit begins with an engaging anticipatory set that aims to help students activate their prior relevant knowledge, and also to elicit information from them to firmly establish time and space before delving into in-depth study. This is particularly helpful for topics like the American Revolution, since most students have learned about it in their elementary school years. In Lesson 1 of The American Revolution: “What Do You Know About the American Revolution?”, students prepare themselves for study in a number of ways. First they are asked to:

Think back to the government types that existed in the early colonies that they have already learned about. What would it have been like to live under that kind of rule?

Students work in small groups to remember the names of all of the 13 colonies, and then are given blank colony maps to fill out. They will then use this map as a reference for the remainder of the unit.

This fun brain teaser accomplishes many goals: through teamwork, students establish a geographic base for a unit of study in which geography plays a prominent role in conceptual understanding. If there are students who feel confident in their knowledge of this information, it gives them an opportunity to shine–and likewise, if there are students who have a hard time remembering specific details, it allows them to obtain the baseline knowledge they need in a non-threatening manner. Then:

Students create a timeline that goes from 1763-1783, and they fill out the events leading up to the American Revolution that they have already learned about.

Once students have established an empathetic and geographic connection, they can now ground themselves chronologically. This timeline activity allows for them to see the cause and effect nature of history–even though the French and Indian War happened in their “last unit,” it is all part of one fluid historical narrative.

Students can see that the time span from the French and Indian War to the end of the American Revolution was only 20 years, and appears to be an effective tool at establishing chronological context. Students can now see the portion of the timeline that is empty, and they know that the events they are about to learn will fit in that time frame.

Perspectives Through Primary Sources

For example, in The Civil War Lesson 4: “How was Citizenship Defined in 1860?”, essential questions are addressed:

- “How were citizenship and citizens’ rights legally defined in the 1800s?”

- “What was the range of philosophical and social understandings of citizenship?”

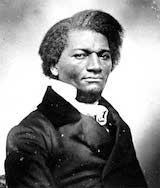

One of the ways the authors suggest getting to this complex understanding of how citizenship was defined is the use of Frederick Douglass’s speech: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. — The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

In this, one of Douglass’s strongest and most pointed speeches, students work on the skill of reading expository text and connecting it to larger themes and essential questions. More importantly, they read the words of an orator directly affected by the disparities in citizenship (and lack thereof) at the time.

These primary sources are rich texts that allow students to engage historical thinking through multiple perspectives, including those who did not always have rights or a political voice with which to express themselves.

Historiography Through Source Analysis

Similarly, in Post Reconstruction Era Lesson 7: “What Really Happened in the American Indian Wars?”, students are told that they will

…act as historians in examining common description of conflicts that occurred in the West between American Indians and the U.S. military by looking at different or conflicting accounts or evidence from these events. It will be our job to try to understand how and why historians make the decisions they do about what evidence is more reliable or trustworthy.

In these analyses, students are asked to compare perspectives, determine what might be missing and what they still don’t know about the situation that might be important, discuss the motivations of the authors, compare differences between accounts, and explain the causes behind the different interpretations.

All this higher level analysis is right on target for the Common Core Social Studies Language standards, which put a strong emphasis on developing historical thinking.

Step Across Time: Reading Discussion Groups

The Civil Rights Movement, still etched in the memory of many older citizens who lived during that time, is a legacy that our young children deserve to experience through the eyes of those who came before them.

- Guidelines for managing and conducting reading groups

- A list of suggested books for reading and discussion that parallel themes addressed in the unit of study

- One-paragraph summaries of each book on the list to allow students to self-select into reading groups based on interest.

We’re Wondering:

One challenge of the history classroom in general is how to move away from the lecture, note-taking, and read-then-answer-the-questions-in-the-back-of-the-book teaching models. As one reads this curriculum, there is a phrase repeated often and in a few iterations: “tell the students”, “let the students know.” This author language gets at the heart of how difficult it can be to have history students construct their own meaning.

Sometimes the teacher just has to come out and tell the students, but despite the well-developed lessons that have the students discovering and examining on their own, these books call for teacher lecture and teacher-led discussion quite often.

Additionally, as classroom teachers of 8th grade U.S. history – the audience for these texts – we would definitely suggest purchasing the text in PDF form. While it might be nice as the teacher to have the physical book in front of you, all of the materials in electronic form would make it significantly easier to share them with your students, whether digitally or in printed form.

Overall, this is an extremely worthwhile tool for United States History teachers to have on the actual or virtual bookshelf. The four-book series can be used by any teacher, regardless of where they are in their career, to enhance their curriculum.

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. — The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. — The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”