One Middle School’s 12-Step Plan for Academic Coaching

Mack Grate is a 6th grade ELA lead teacher at John Ericsson Middle School in Brooklyn, NY. The school program she describes here will be presented at New York City’s regional ECET2 Conference at Pace University in August.

After mulling for three years over the idea of a program for extra student academic support, our school rolled up its collective sleeves and created a custom intervention designed to ensure that every young person – from our more advanced pupils to our struggling learners – will have their individual needs met.

We began our work to create ACE (Academic Coaching at Ericsson) after faculty members researched Response to Intervention programs and their importance. As we set out last summer, little did we know that ACE would revolutionize how all stakeholders at our school viewed their roles in the success of our students.

Ericsson Middle is a Title I School with a diverse student population. About a third of our kids are Special Education students and a third are English Language Learners. Recently. we’ve also begun to receive an influx of students reading above grade level.

For others who may be considering an academic coaching program, here are some steps I’d recommend, with tips and lessons learned so far. (I’ve also included links to a series of ACE articles at my personal blog that provide more information.)

Step #1: Create a vision

First, begin by identifying the core problem on a granular level. Through that process your vision for your program will emerge. For us, we have a significant number of readers who come to us well below grade level each year. And just this year we are beginning to get an influx of new students who are reading well above grade level.

Having such a disparity makes it difficult to address the needs of both these groups through a set curriculum. We felt we needed to create an intervention and extension program to ensure we were really moving all our students forward, not just the lowest third. Our vision was to create a program that did all of the following:

- Tracks students’ reading and writing data school-wide and provides a systematic way to help accelerate all students’ learning, especially those who are reading below grade level.

- Provides an opportunity to differentiate learning for our advanced students.

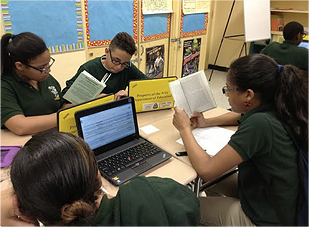

- Provides targeted small group instruction organized around specific skills individual students need to master.

- Organizes groupings based on data that is routinely collected and analyzed.

- Allows cycles and groupings to change frequently based on mastery of skills.

- Supports content teachers to learn how to teach literacy skills directly, and ultimately leads to the infusion of more reading and writing across the curriculum.

Step #2: Meet the needs of all stakeholders

The vision has to cater to everyone’s needs. If it does not then you will be met with high levels of resistance. With that being said, expect push back, because it is inevitable with change. The goal is to minimize it by trying to address the needs of all parties.

The needs of our teachers were quite different. Many felt uncomfortable teaching literacy strategies, so at first we needed to provide them with lessons that were already written. Then, we planned to support them with professional learning throughout the year so they could get to a place where they felt more comfortable infusing literacy strategies into their teaching.

The principal needed a system to track all students so that she could clearly identify which ones were moving forward and which ones were not. The school psychologist and counselors needed a more systematic referral process for special education evaluations. All of these stakeholder needs were taken into consideration and built into our program.

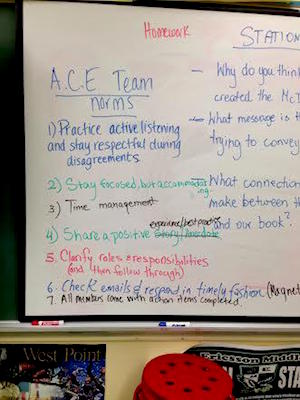

Step #3: Create a committee

In order for this work to be impactful, we needed manpower and individuals who could help garner buy-in.

Step #4: Develop common benchmark assessments

Having a common measurement of progress is essential. All students then know what to expect, how they will be assessed, and how that will play into what group they are placed into. We chose two: first, multiple choice assessments that we created in-house to isolate the standards that our students struggled with the most on the ELA exam last year. Second, we utilized Lexile level assessments on myON.com to help students track their progress and assist us in organizing leveled reading groups that put the right students together.

Step #5: Figure out scheduling

The time slot you place the program into can make or break it. This year ours was first period Monday and Thursday (terrible idea). Next year it will be embedded into the middle of the school day three times a week, right before lunch (much better idea).

Sometimes you may not have the ability to fit your initiative into the school schedule where you would most like to see it. In that case, you have to brainstorm and figure out ways to make the best of a less-than-optimal situation – like we had to do this year.

Step #6: Create systems for data collection

For data to be useful, it has to be accessible by all, updated frequently, analyzed, and used to shape instruction. Our solution was to create a schoolwide spreadsheet on Google Drive and share it with the entire staff.

Our spreadsheet (see “Tracking the Data” here) includes everything from students’ state exam scores from last year; any modifications they are entitled to; their Lexile levels (which are updated monthly), and their benchmark assessment scores. Teachers can then view the data of any student or class in the school. If they get a new student in their group, they have a quick at-a-glance summary of their performance levels.

Step #7: Create systems for differentiated lesson plans

Early on, it may be necessary to provide teachers with lesson plans while you are in the process of training them how to be able to create them independently. In our case, we wanted to help teachers become more proficient at infusing literacy skills into their instruction, so we had to provide differentiated lessons initially while simultaneously delivering the training to do this on their own in the future.

When creating the lessons, we had to norm our template, sift through lesson ideas, analyze the Lexile data and then delegate who was going to write what level. We ended up having our speech therapist write the lowest level lessons that involved directly teaching decoding, because that was her area of expertise. A newer teacher who was still building a tool belt for differentiation focused on the higher level of instruction, because that is where he felt most comfortable for the time being. Meanwhile, seasoned ELA teachers focused on writing lessons that differentiated the lowest 3rd because these veterans were strong at building in scaffolds.

However you delegate the lesson plan writing, make sure that the lessons are consistent and work towards the goals that you have set for your initiative.

Step #8: Use feedback to increase buy-in

We surveyed (and still do) students, teachers, staff and parents often to get new ideas on how to fine-tune our program to meet everyone’s needs. If the adjustments can be made without compromising the integrity of our program, we are quick to make them. If they can’t, then we acknowledge the suggestions and explain why we cannot make that change at this particular time.

All this goes a long way in terms of helping everyone’s voice to feel heard and to understand the reasoning behind difficult decisions.

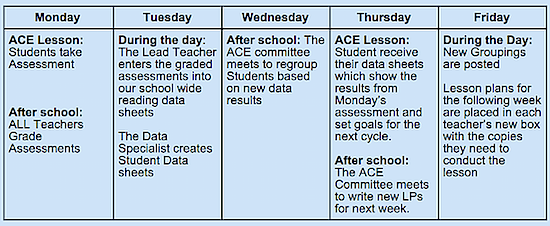

Step #9: Develop protocols for organizing groupings

With groups changing often and the groupings playing such a key role in cultivating motivation within the students and providing us with the ability to accurately deliver targeted instruction, it is imperative that the process is manageable, timely and routine. Here is our weekly routine when reshuffling groups:

Step #10: Invite outsiders to get their perspective

Sometimes when you are too engrossed in your initiative, it makes it difficult to see it from an unbiased perspective. One way to ensure your community doesn’t fall into this trap is to invite outsiders to do a walkthrough of your initiative. Present what you have done and where you plan to go and have them see it in action.

We did this (in a flurry of activity). Following the walkthrough, we had a question and answer session that provided us with valuable ideas on how to build on what we had created thus far.

Step #11: Evaluate effectiveness of the program

Although we haven’t done this for our own ACE Program yet because we haven’t reached the end of the first year, it is important early on to establish the criteria by which you will evaluate your work. If you do not, it may fall subject to a default evaluation based solely on the state exam scores.

While state test data could be a valid way to partially measure some aspects of a school’s progress in solving a problem, in the early stages it might simply confirm that a problem exists. We know, for example, that our teachers feel more capable of infusing literacy into their instruction and now have a common understanding of what a 6th grade level text looks like. But it’s too soon to expect the full impact of those new understandings to show up in state test results.

You may be able to find evidence in outside data, but developing a direct assessment first is a better way to ensure your initiative met the goals you originally set out for it to meet.

Step #12: Refine as you move forward

As always, reflections and evaluations highlight significant improvements which are important to recognize and celebrate. But they also provide valuable insight into areas you can improve upon further. So once you have implemented your evaluation, examine the data closely and share it with the various stakeholders. Document your key learnings. Elicit from everyone what your new goal is and begin the refining process for the following year.

This meme perfectly sums up what I have taken away from working with this team to roll out our ACE initiative. In fact, it’s difficult to look back and imagine how we got by before. I guess that’s just it, we didn’t. We also didn’t realize there was so much more we could do to take control of our situation. There is never any excuse for allowing kids to fall through the cracks, and unfortunately for so long we did. We are working really hard to remedy that now. – from Mackenzie Grate’s blog

For a more in-depth look at each step of the ACE process and the sample templates we used, visit this ACE articles page at my blog. Any tips, suggestions or ideas for implementation are always welcomed! Tweet me @ThisTeacherSays.

Mackenzie Grate (@ThisTeacherSays) has been a Title I middle school teacher leader in New York City for the past 8 years. She has a BA in English Education and an MS in TESOL from New York University. She is currently earning her MA in Educational Leadership from The College of Saint Rose. Her hope is to one day open a school with her colleagues based on a collaborative teacher leadership model. Read her musings about all things educational at her website.

This twelve step plan for education is very very good. It’s amazing to tap the child’s resource and make the students give better performances. Needless to say it is interactive and a stepping stone in revolutionary approach to education.