4 Ways to Motivate Kids to Tackle Complex Text

By Anne Vilen

By Anne Vilen

Picture a class full of eighth graders groaning in protest when you hand out the article you want them to read today. “Yeah, right,” mutters one, pushing the article onto his neighbors’ desk and guarding his space with a fortress of elbows, jacket, and lunch.

Surveying the scene, you know it’s going to be a long battle. How do you convince your students to take on the challenge demanded by more rigorous reading standards?

Kami Spampinato, a seventh grade teacher at Ida Jew Academy, a K-8 charter school in San Jose, California, confirms that what school-weary middle-schoolers respond to is not a “just do it” approach, but instead these three things:

- A real-world purpose;

- The momentum of other ordinary, striving, often-bumbling learners;

- A little individual attention.

Spampinato describes four moves that get her students to “buy in” to reading complex text.

Choose a text that’s relevant and purposeful

When Spampinato asked her students to read a speech by Cesar Chavez, students were pretty intimidated by the rhetorical challenge of the genre. But they were also intrigued because many of their own relatives work in the same California fields Chavez talks about.

Real-world relevance provided a doorway into the text, allowing her to focus on stretching reading skills particularly required by this kind of text. (For more on what questions teachers should ask as they prepare to teach complex texts, listen to EL Education’s program director Cheryl Dobbertin’s recent interview on Bam! Radio with Larry Ferlazzo.)

Feed the social animal in middle school kids

Spampinato’s next hurdle was how to deliver the lesson. She taught protocols for collaboration that get students out of their seats and hold them accountable for reading, thinking, talking, and writing with partners or small groups every day. Such protocols anchor reading instruction in EL’s free Common Core aligned curriculum, including the module on Working Conditions that includes the Chavez speech.

“They want to be more social,” says Spampinato. “It feeds their need to process everything verbally. And because the protocols are structured and purposeful, students build on each other’s understanding rather than tearing each other down.”

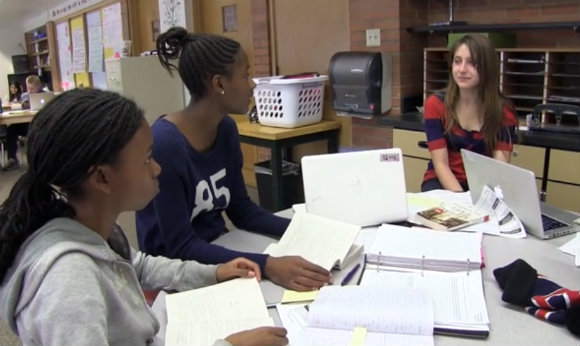

To see what it looks and sounds like when middle school students work collaboratively in this way, watch this video about “getting ready to write.”

Boost students’ confidence

Building readers’ competence starts with pumping up their confidence. They have to want to do it, notes Spampinato, and that means they need to know they will not be exposed to ridicule and judgment. She shares the story of a student who was so anxious about reading aloud in front of peers that one day she just walked out of class and left campus. When Spampinato caught up with her, the student confessed, “The words are so big. I don’t want to pronounce them wrong because people will laugh at me.”

Spampinato was empathetic. She shares with her students that she also struggled mightily in middle school. To help this student overcome her fear, Spampinato gave her part of the reading ahead of time and helped her to rehearse “in secret” before getting called on in class. “All she needed was a little advance notice and some basic vocabulary instruction. Now, even without this intervention,” says Spampinato, “she speaks up. She tries.” See how a 7th grade teacher supports a diverse group of learners in this video.

Foster collective commitment

What really changes individual readers’ attitudes is raising the tide of collective commitment in the class. Students learn that when they first grapple with complex text collaboratively–parsing it one word at a time, reading sentence for sentence, persisting paragraph after paragraph, cheered on by peers and teacher–they can eventually understand it individually. Students compare notes as they annotate the text with questions, connections, and summaries. They extract evidence for an author’s claim and debate whether the evidence is logical. To hear what middle school students themselves say about what helps them read hard text, listen to these students in an eighth grade classroom in Homer, New York.

What’s more, by making it okay, indeed respectable, to try hard things, teachers like Spampinato invite students to have their literacy cake and eat it too. Year after year, teachers or employers will ask these students to learn something new and more difficult. When they learn how to rev the “I can” engine that drives life-long learning, they are more likely to step up and tackle any challenge.

Anne Vilen taught language arts in middle school and served as a school administrator. She coaches school leaders and teachers and is a writer for Expeditionary Learning. She is coauthor (with Ron Berger, Suzanne Plaut, Cheryl Dobbertin, and Libby Woodfin) of Transformational Literacy: Making the Common Core Shift with Work that Matters.

What great information, Anne! Even a science teacher (my former profession) can use this. After all, our kids have to read science texts! I especially like the section about “feeding the social animal in kids.” It certainly beats keeping them in straight rows and preventing any interaction at all. Thanks!