3 Ideas to Better Prepare History Students

A MiddleWeb Blog

Students often take U.S. history three times during the course of their K12 education – in elementary, middle and high school. We might guess that by the time they get to high school, students would be well-prepared for advanced studies. But if you ask any group of high school U.S. history teachers about this, you will get an earful:

“I had a student who didn’t know which side won the American Revolution!”

“I had a student who thought the assassination of Lincoln was what started the Civil War!”

“I had a student who thought the Declaration of Independence freed the slaves!”

It becomes a competition to see who can provide the most outrageous example of student ignorance. (If it makes history teachers in the pre-high school grades feel any better, there is a whole crew of college professors out there wondering what in the world those high school teachers are doing!)

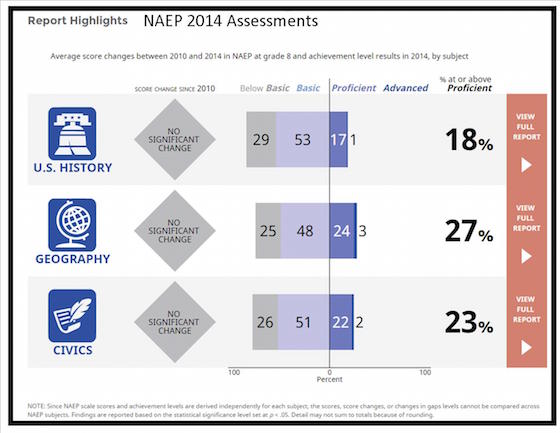

And then there’s the NAEP

Recent headlines about the 8th grade NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress) test in U.S. History, Civics and Geography echo the high school teachers’ concerns:

► “Eighth Graders Flatline on NAEP U.S. History, Civics, and Geography Tests”

► “Another Piece of Evidence that America’s Students Know Little About Their Country”

Not just the facts, ma’am

Really, if you look back at the data, American students have never been particularly knowledgeable about history. The problem probably has much to do with what too often passes as history teaching at any grade level. If we limit our teaching to acquisition of facts, students will forget them soon after they learn them.

But let us assume that those of you reading this post are not just teaching history as one fact after another. Then here’s the question I have:

What do we need to do as middle school teachers to build on what was done in grade school and help provide the necessary background to help our students succeed in high school?

While there certainly are differences between middle schoolers and high schoolers, in my experience, the differences are often exaggerated. In fact, dwelling on the differences can be detrimental if there is a hidden assumption that we need to “dumb it down” for middle schoolers. Kids need to be challenged at every age. And good teaching is good teaching, at any level.

So here are three suggestions that can help us strengthen our U.S. History classrooms across the board.

1. Talk to the teachers before you and those ahead.

Wouldn’t it be useful to know what was taught in elementary – and to share what you have in mind for the middle? (Whether or not students learned what was taught is a different question.) Explore the possibility of a chat with some history-minded teachers at your elementary feeder schools.

And wouldn’t it be helpful to ask the folks in the high school history department about the things they wish their students better understood? It might be something related to content, but it might also be providing students more practice in analyzing primary sources or in learning to write a history paper or debate a historical issue.

If a small study group can be organized, a really productive conversation might center on the Common Core history/SS standards for grades 6-12 and how the teaching responsibilities embedded in those standards might roll out.

You may not have the opportunity to have these collegial conversations as part of formal professional development, but who’s stopping you from sending an email? It’s almost summer….send out a few emails. Go out for coffee with the history department chair at the high school. Try to get some dialogue started.

2. Emphasize historical periods.

Perhaps instead of giving multiple choice and fill-in-the-blank tests where students can be tested on facts they will soon forget, we should do more “unit reviews.” What if your assessment asked just one overarching question: what was the most important trend during the time period covered by our last unit on ______________ ? And how did this develop from our previous unit on _____________ ?

What if you did that after every unit? And then, before you started the next one, you reviewed a few key things that led to the next era?

Lessons that emphasize the key driver of cause and effect can help facilitate this. Even if you teach thematically – an approach discussed at length in a recent MiddleWeb post by Sarah Cooper, you will want your students to understand these broad chronological periods.

For example, what if our students could offer up a summary like the following:

In our unit on Colonial America we saw that the colonies grew and become increasingly economically & political self-sufficient. This led to our unit on the American Revolution in which the colonies wanted no taxation without representation, and so broke away from Great Britain. They were convinced that a republican form of government was best and so when the Articles of Confederation didn’t work out, they wrote a new Constitution.

3. Avoid an overly cynical teaching style

Let me be clear: I am NOT advocating that we teach only a “rah-rah, isn’t America great” narrative, as many on the Right have suggested in response to the 2015 changes in the AP U.S. History Exam. And I do not think we should tell falsehoods to shield students from the dark side of human actions and events. Good history teaching must interweave multiple narratives.

But, within those narratives, we do have to consider what our students are intellectually ready for and what they are not. Middle school might not be the best time to share everything you know about political expediency and corruption, pragmatic compromise or the nitty gritty details of electoral politics. It doesn’t mean that we can’t teach about these things, but if we are not careful, we risk fostering a pre-mature cynicism about the world and students’ ability to effect positive change.

We seem to understand this imposition of limits intuitively when it comes to things like sex and violence. But it’s more complicated when applied to history teaching.

Let me give an example from personal experience…

It was a great question. How to answer without sounding like his middle or grade school teacher taught him a lie? I answered with a question: when you were younger, what do you think your reaction would have been to the whole truth?

We discussed it for awhile, and he reached the conclusion that he might have thought Lincoln was a hypocritical jerk and just wrote the Proclamation to try to win the war, not really caring about slaves. That view isn’t exactly wrong, but it’s not terribly sophisticated either.

So we have to think carefully about how we teach complex topics to middle schoolers without teaching beneath their abilities or their rapidly growing capacity to understand the larger social world. It is a delicate balance, but a critical one, if we want to help our students.

We are part of a teaching continuum

Too often, we think about what we do in the history classroom in isolation, without careful thought to what students have learned in elementary school or what they might be studying in high school. What tools do we want to give students so they can succeed at the next level? How do we avoid needless repetition of content?

With summer quickly approaching, let’s put these important questions on our agenda now, so we can reflect on them before next year.

Lauren S. Brown (@USHistoryIdeas) has taught U.S. history, sociology and world geography in public middle and high schools in Chicago and Wisconsin. Currently, she supervises and evaluates social studies pre-service teachers at Northern Illinois University, where she has also taught the social studies methods course. Her degrees include an M.A. in History from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her blog U.S. History Ideas for Teachers is insightful and packed with resources.

Of course we are a part of a continuing curriculum, but the research has been very clear for over 10 years that social studies including US HIstory are not being taught in the majority of elementary classrooms throughout the U.S.A. Why students do not remember things they are taught has to do with a number of factors. One of those is the inabilities of younger students to recognize the importance of events and to link them together into chunks of information that they can remember or remember accurately.

I am aware of this problem at the elementary school level but know little about it. I think part of that problem stems from the fact that social studies educators are focused on the upper grades and the elementary school educators have to be focused on so many things at once (i.e. literacy & math) and so social studies gets left out.

And I think you’re right about “chunking.” Sarah Cooper’s recent post on this site discusses this at length. It is a topic that deserves our continued attention, I think.