History Students Create Children’s Books

A MiddleWeb Blog

“Your children’s books should be understandable by a second or third grader,” I tell my eighth grade history students, “but do not necessarily need to be appropriate for a child that age.”

“Your children’s books should be understandable by a second or third grader,” I tell my eighth grade history students, “but do not necessarily need to be appropriate for a child that age.”

In the way of all teacher jokes, this line usually elicits a smattering of uncertain laughter from the class. This is perfectly acceptable, as the remark is intended to serve a pragmatic end, not launch my career in comedy.

Regardless of how funny or unfunny they find my jest, students are now aware that the primary goal is to distill what we have learned into clear, simple language. As we move forward with the project, I regularly remind them that this is our primary goal: to make the content comprehensible for a seven year old.

As you read my account here, keep in mind that I developed this children’s book project with the particular needs of my students in mind. While I believe the project can be adapted to any classroom, the scaffolds are intended to support students who struggle with literacy and knowledge retention. In my inner-city middle school, that’s the norm.

Origins

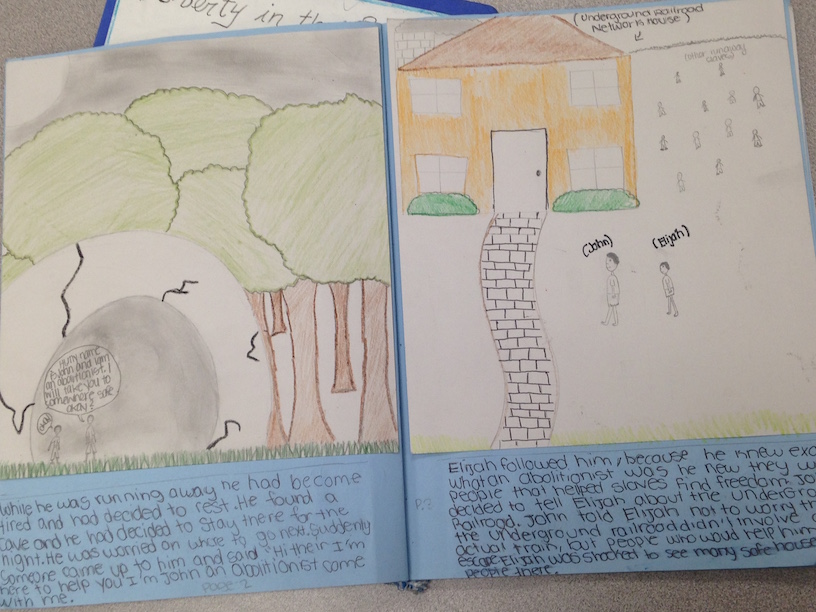

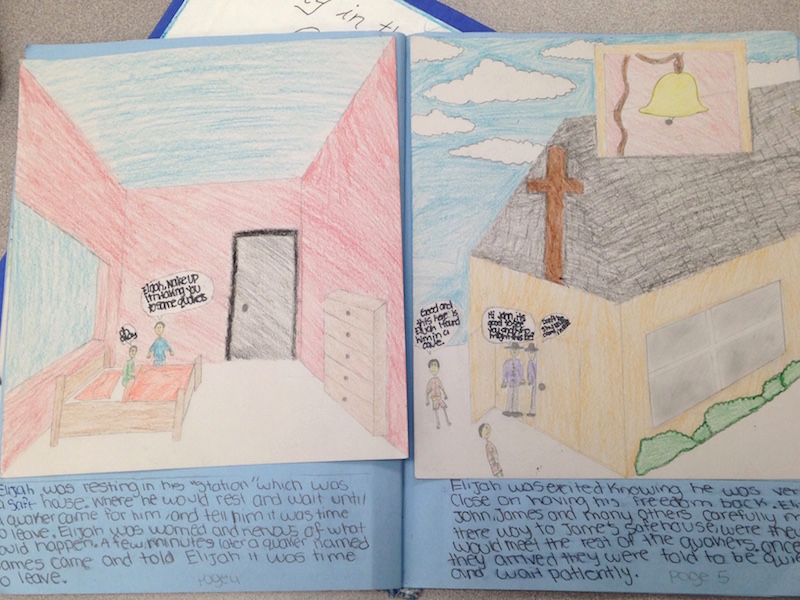

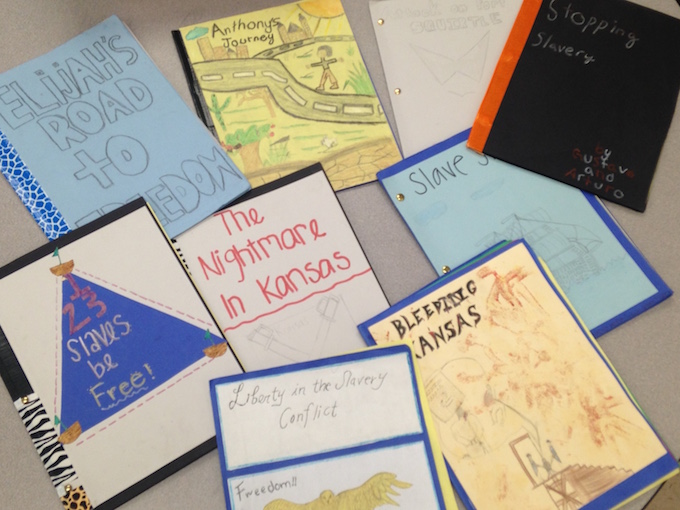

The description of the project itself is straightforward: students work in groups to create a children’s book based on the content of our current unit.

When I conceived of this project a few years ago, it suffered from a lack of purpose and structure. It was a project for project’s sake, and I did not anticipate the myriad difficulties my students encountered. Among other things, I assumed (incorrectly) that “creative” was synonymous with “easy.”

The notion was that an art project with few constraints would miraculously help students comprehend complex texts. However, when the projects were completed, it was clear that many students struggled with both the content as well as the writing process itself.

Despite these challenges, the project had value for my students. They developed teamwork, summarizing and time-management skills. Many students were also motivated throughout the process and were excited to see the final product.

The Project Now

The Project Now

I have since restructured the project to include additional scaffolds and a clearer sense of purpose. Students begin, as with most of my units, by reading and annotating secondary sources (many of them summary texts I have written for them myself). I then introduce the project, and ask each team of 2-4 students to select a person, event or idea about which they want to write their children’s book. Students are encouraged to select something or someone that they find personally interesting, as they will be focusing on that subject for several weeks.

Once students have selected their focus, each team is presented with a selection of possible texts that can be used to conduct additional research on their subjects. Student groups are instructed to select two texts and read the pertinent sections. Students then complete a handout (I use an I-chart) that helps them identify similarities and differences between the texts.

While it is tempting to turn this into a full-blown research project, I found that to be counter-productive in classrooms where the majority of the students are struggling with the reading comprehension alone. I have tried to find a comfortable middle ground; I provide students with a choice and ask them to compare the perspectives of the authors. These are fundamental elements of research with which many of my students need practice.

Students then use the I-chart to complete a few constructed responses (long answers to questions that include citations from the text) that help them to narrow the focus for their children’s book. The idea is to get students to identify:

- What is the most important

- What is the most interesting

- Which text they had an easier time understanding

The last of these responses is the most important for most of my students. I work with children who, if asked whether or not they understood what they just read will ALWAYS say yes. If, as a follow-up, I ask them to explain a particular part of the text, most will immediately admit they do not know the answer. This is not prevarication. My students literally do not know when they have failed to understand a text, and many do not even grasp that the goal of most (if not all) reading is comprehension.

Analyzing which text was easier to understand forces students to reflect on what they did or did not understand and is a step toward metacognitive awareness of their own learning. For the purposes of the project, I tell students that this question is to help them write simple prose for the intended audience of the children’s book.

The importance of storyboarding

After completing their constructed responses, students work together to create a storyboard. Again, this is not merely intended to help them with the book. The storyboard is an opportunity to teach or review concepts like chronology or cause-and-effect.

In early iterations of this project, skipping this step meant that many of the books were a random assortment of pictures and words copied from different parts of a history textbook. The storyboard is when the students first begin thinking of the book as a narrative, which is an important conceptual framework for students to develop in history class.

Regardless of the quality of previous teachers, many students continue to see history as an amorphous mass of disjointed facts. The storyboard drives home the way people and events in history have affected one another, and can even bring events to life that had previously seemed dull or meaningless.

Finally, once I have personally approved the storyboard and seen that all other elements of preparation are completed, students can gather up supplies and begin working on the book. At this point, the project moves forward like many others. I set out basic expectations about group work and have students periodically reflect on their progress as they move forward.

For the most part, however, I try to fade into the background during the final stages of the project. This is my opportunity to let students succeed and fail on their own terms, and to see which skills they have mastered, and which will need reinforcing after the books are turned in.

Final Thoughts

The average quality of the children’s books I received this year is markedly better than those of previous years. I am fairly confident that this is the result of the structured activities that preceded the creative portion of the project. From a pedagogical standpoint, I had to think of this assignment as synthesis and assessment, rather than treating it as a content-teaching tool.

The remarkable thing for me was watching students become so invested in the project that the content became second-nature, with some students re-teaching others about certain concepts and events in order to make certain they could contribute to the creation of the book.

To a lesser degree, I enjoyed listening to my dorky joke repeated numerous times, as children debated just how graphic to make their books, given that they are intended for children.

Thanks for sharing this process. I appreciate that something like this can’t be replicated “as is” with another group of students. However, you give enough detail that another teacher could consider whether or not and how to do something similar with his/her students. I was wondering if these books were ever read to the grade 2 or 3 students they were written for? If not, what do you think about that idea?

So far, the goal of having my students read their books to elementary children has yet to be realized. This is largely due to both timing and quality issues. If you can pull it off, I endorse the idea wholeheartedly. Thanks for the interest.

Hi, Aaron!

I’ve been doing research and a lot of reading over the past few weeks in order to prepare for the process of earning National Board certification this year. I’m very impressed with your idea, and I plan to adapt it for my own purposes this year. As I read, I kept thinking, “Now WHY didn’t I think of that???!!” I teach both gifted elementary enrichment to K, 1st and 2nd grade students and gifted-H English I to 9th grade students, so this is something that I’ll definitely use. Thank you for sharing! :)

Two links you might like on this theme: http://www.activehistory.co.uk/Miscellaneous/menus/GCSE/mr_men.php and then http://www.activehistory.co.uk/gove.php.

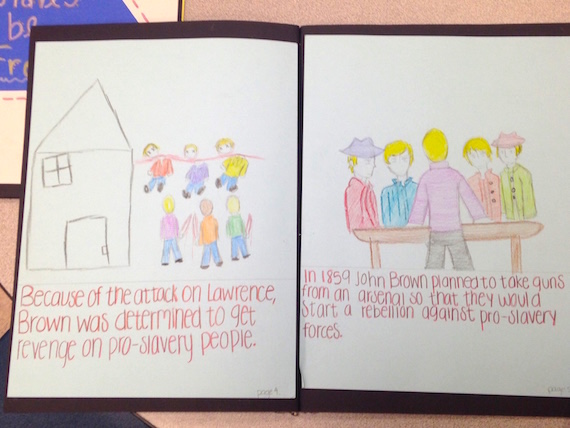

I am a sixth grade teacher of humanities, with a large focus on U.S. history. I teach a gifted program, probably at an 8th or 9th grade level. I utilize a lot of primary sources that I provide either through websites or my own personal book collection that I keep in the classroom. We do a lot of project based work based upon a chronological analysis of history. As the Civil War is one of my favorite topics, we combine research with brainstorming as to the whys things have happened. One small project was John Brown, terrorist or martyr. The students created a poster board individually supporting each of their own positions which then was followed up by a town hall type discussion, once again using primary sources as well as their own opinions. I think combining your booklets with a reading to the lower schools would be great. Keep up the good work.

Great PBL :)

I started using this technique in 2005 in many of my college child development classes. Last year, one of my student’s published a book she created as a class assignment. I’ve found that creating books helps students focus on the purpose of the content when they find than they must use it to create a picture book.They also discover how limited the variety of topics are for serious content for children’s books. My students have written books on autism from a child’s point-of-view, bullying, food safety, health, family matters, and so on. Creating books is a student-centered way for learners to show what they know.

Great Project! Have you ever thought of adding some 21st century skills to this project by asking students to make the “final product” using online digital book software? There are lots of good ones but I like Tikatok.com. Kids can scan their drawings, upload them, then place them on the page. They can write and illustrate each page just as they have on paper. They can then have the book printed and bound or download the pages as a pdf and print it locally themselves. Kids love making digital content—they do it everyday in real life. The end product is very professional looking and gives the kids skills using the online software. I’d ask the PTO to fund it for a year. Donate coipes of the books to the elementary school library!

Unfortunately, this is simply unrealistic for my context. One of the limitations when working with impoverished adolescents is difficulty funding such activities and utilizing technology. Even when I have access to the computer lab, I cannot always promote what many think of as “21st century skills.” My students simply struggle too much with basic literacy, and more often than not, do not have access to computers at home. This means many are unfamiliar with the basic computer skills. Given that I have only so much time with each class, I cannot take it upon myself to spend the whole year teaching computer skills.

I completely understand your situation. In the end the basic literacy is the most important. Keep up the good work!

As I go from 6th grade to 1st grade everyday, this is a SUPER project to have my middle schoolers do for “informational writing” unit while my primaries read for “informational reading”

Aaron Brock do you happen to have a write-up of this project with the requirements, page numbers, etc.? How would you modify this assignment if a kid worked on it individually? Any info would be so helpful – thank you so much!