Nurturing a Culture of Teacher Inquiry

By Kevin Hodgson, Rick Haggerty and Jamilla Jones

“If you were to walk into any of my classes on days leading up to Socratic Seminar, you would observe my most studious student and my most disruptive student actively engaged with not only the text, but with each other … “ — Jamilla Jones, English Language Arts Teacher

Inquiry forms the heart of discovery and learning, from early toddlers making sense of their world to grown-ups wondering how the latest mobile app works on their device. We investigate. We try something new. We evaluate. Adapt. Reflect. Try it again.

While many educators often ask their students to go through an inquiry process — in the form of research papers, or science experiments, or even literary analysis — many teachers also need to be reminded that they are always learning, too, and their own classroom environment can provide the perfect setting for meaningful inquiry and research.

Our Inquiry Project: Writing Across Classrooms

This past year, teacher-consultants with the Western Massachusetts Writing Project worked closely with content-area teachers at the STEM Middle Academy in Springfield, Massachusetts, on topics related to the teaching of writing in all classrooms.

The activities provided opportunities for STEM Academy educators to consider and refine the teaching of writing in the content areas, explore how best to use writing to inform learning practices, and support a community of “teachers as writers” at the Academy.

All of the professional development was built around an inquiry model of the National Writing Project and the final project for the year-long discussions was a classroom inquiry research project, in which teachers considered their own students and their own core instruction, and then designed and implemented a research project for their classroom.

As a culmination activity, teachers then shared out their inquiry projects, and their findings and reflections, with each other. In doing so, the staff at STEM Academy built trust among each other and shared best practices.

This article is a writing collaboration by three members of the partnership — Kevin Hodgson, a teacher-consultant with the Western Massachusetts Writing Project; and two STEM Academy teachers, Jamilla Jones, an eighth grade ELA teacher, and Rick Haggerty, a special education teacher — to document the ways in which teachers engaged in their classroom research and to provide one possible path for other educators who are considering their own classroom as the setting for research and inquiry.

Why is inquiry so important?

“Regardless of whether you teach elementary, middle, or high school science, misconceptions are tenacious and often follow students from one grade to the next. Taking the time to elicit and examine student thinking is one of the most effective ways to support instruction that leads to conceptual change and enduring understanding.” — Alimany Conteh, Science Teacher

Why use the inquiry model in a classroom? Many teachers, including ourselves, have asked themselves that question. The very frank answer is because inquiry is how we all learn throughout our lives, so why not engage students and ourselves in this type learning in the classroom? From birth babies learn by constantly exploring their worlds through their senses. The process of inquiry begins by gathering information through our senses.

It could not have been said any better than that. If students have the opportunity to investigate a topic, their learning will increase. As educators we have to go beyond data and information accumulation and move towards useful and applicable knowledge. Inquiry is not so much about finding the right answer, but about the need to seek appropriate resolutions to questions and issues.

An inquiry-based classroom teaches students and educators alike to become problem-solvers instead of passive receptacles that absorb content knowledge given by teachers. To put it bluntly, content knowledge in specific disciplines is continuously expanding and growing so no one person will ever be taught or learn everything.

However, educators can help students develop and nurture the skills and attitudes needed to continuously learn, and this is what inquiry-based learning fosters. As Lloyd Alexander notes, “In some cases, we learn more by looking for the answer to a question and not finding it than we do by knowing the answer itself.”

As for students, so too for teachers

“The graphic organizer “helped me identify gaps in student understanding of what constitutes relevant evidence, as well as locate comprehension breakdowns when several pieces of evidence were overlooked during reading and the most attention-grabbing cause was settled upon for the response.“ — Wendryn Case, History Teacher

In looking back again at the projects the STEM educators took on this past year, it is clear that many were working in familiar terrain, building off the teaching practices that were already in place. They were taking the next step to improve student learning.

Some examples of our teacher inquiry projects:

(click links to see PowerPoints)

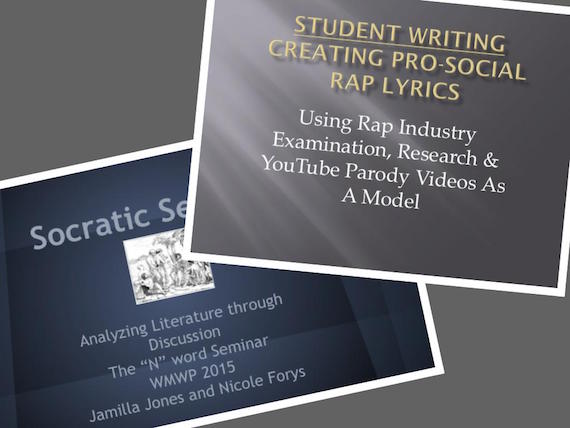

- Using Socratic Seminar to analyze literature around race and language. With the novel To Kill a Mockingbird as the main text, the Socratic Seminar inquiry engaged students in spirited discussions around the language of oppression.

- An examination of the genre of lab reports in a science classroom provided more clarity for how to teach the writing of those reports. A science teacher explored the concept of “interactive notebooks” as a way for students to better understand how to write about science in a meaningful way within the field of study.

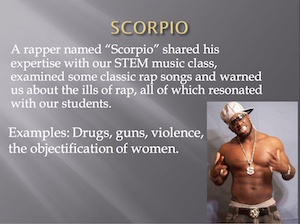

Turning social media on its head, another inquiry project looked at the lyrics of rap and hip-hop and used the concept of the YouTube parody video to inspire students to write pro-social rap lyrics of their own.

- Formative assessments, or learning probes, were the heart of another inquiry endeavor by a science teacher, who wanted to understand better how to keep track of student learning outside of the traditional summative unit tests.

- With the push on using evidence to support analysis, one inquiry project dove into the idea of graphic organizers as a tool for learning and reading, particularly around collecting and analyzing evidence from the text.

- A science teacher grounded an inquiry project around health, using a data tracking system and the book Chew on This, to help students consider the consequences of life-style choices and the impact of nutrition and exercise on the human body.

- An inquiry project examined how close reading strategies work, and don’t work, for English Language Learners, leading to the understanding that all reading has social contexts that must be brought into an ELL reader’s framework, as “cold reading” without background knowledge of text is an unfair burden.

Easing concerns about classroom research

“Through our inquiry, we realized the importance of the development of background knowledge to negotiate meaning of a text. While close reading is an excellent tool, it should not be used in isolation. Close reading should be accompanied with other strategies that will facilitate access to the text.” — Yanira Rivera and Alva Laster, ELL/Special Education Teachers

During the early spring, WMWP facilitators sought to provide support for STEM Academy teachers on their classroom inquiry projects. The first hurdle was getting past the phrase of “classroom research” itself — which made some of the Academy teachers anxious about the expectations of them for this kind of inquiry.

To help ease concerns, WMWP facilitators shared a video overview of Classroom Inquiry built on forming a question, conducting outside research, designing a classroom activity, gathering student work on evidence, and then reflecting on the process and results.

WMWP also brought in a recent participant of the WMWP Summer Institute who had conducted classroom research herself. Every participant in the WMWP Summer Institute is expected to conduct a classroom inquiry project throughout the school year.

This guest speaker, Allegra D’Ambruoso, shared her inquiry presentation about teaching research skills in the library at another school in Springfield, and more importantly, she explained her own thinking and process with implementing her inquiry endeavor, and she answered questions from the STEM Academy teachers.

“I learned that students were very in tune with what YouTube is playing. It is important to intervene so that their learning, writing and speaking can become more prosocial and less destructive. This means that students are not learning in a vacuum and their learning is influenced by media. So having students examine what media is feeding them, having them write and even record their own prosocial lyrics, can help them contribute to turning around a rap industry that is more often based on profits and not art.” — Rick Haggerty, Special Education Teacher

The STEM Academy staff was then divided up into smaller teams, with each team designated with a “coach” from the WMWP facilitator.

While the initial plan was to use an Edmodo social networking space to connect coaches with teams, that idea was scrapped when it became clear that many STEM Academy teachers were either not interested or not technologically-savvy enough to benefit from using Edmodo as a connecting point. Instead, coaches checked with teachers via email or in person during after-school drop-in sessions at the STEM Middle Academy.

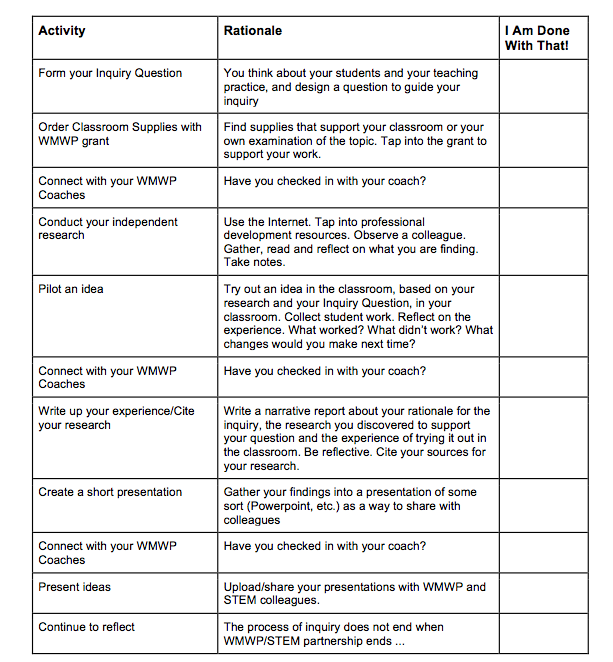

Despite the support, many teachers were still wary of the research project, so additional supports were put in place, including detailed checklists (see above). There was also the added tension of state-mandated testing at the school, and spring break.

The building principal generously allowed teachers time during grade-level meetings to work on inquiry presentations, and while many were finished right on deadline, the resulting sharing session was a powerful example of the National Writing Project’s motto of “teachers teaching teachers.”

Professional learning is becoming “high stakes”

“Incorporating Howard Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences into lessons seems to increase the amount of student engagement in my classroom at varying degrees. It also allowed for more student interaction and discourse which created further opportunities to internalize the content. “ — Laurie Roule, History Teacher

A survey of STEM Academy teachers conducted in the days following our inquiry project sharing indicated that many of the teachers found the inquiry process valuable, but time-consuming. A few expressed that taking on practice-related research was too much to ask for from burdened classroom teachers.

While we acknowledge that teachers have a lot on their plate these days, we would argue that inquiry has a special place in the teaching profession. Recasting teachers as learners, as classroom inquiry does, allows us to explore areas of interest with a meaningful lens for improving instruction.

In this age of teacher evaluation, now nearly in full effect in our state of Massachusetts, professional growth “indicators” or categories will be front and center. We have to “prove” to our administrators that we are making progress in defined areas of our profession. Inquiry projects provide agency for teachers to define those areas and show data from research.

About the authors

Jamilla Jones is a long time 8th grade ELA teacher and Literacy specialist. She has spent most of her years teaching students in urban areas and regularly coaches her peers in areas of engagement and literacy. She now works with teachers in the areas of Social Justice at Duggan Middle School in Springfield, MA.

Rick Haggerty is a Special Education teacher at STEM Middle Academy in Springfield, MA. He teaches learning-disabled middle school students in a pullout classroom and covers ELA, Math, Social Studies and Science.

Kevin Hodgson is a sixth grade teacher in Southampton, Massachusetts, and a co-director of technology with the Western Massachusetts Writing Project. Kevin blogs regularly at Kevin’s Meandering Mind and tweets more often than is healthy under his @dogtrax handle. Follow his ELA blog Working Draft here at MiddleWeb.

I very much appreciate and admire the staff collaborating on something like this–especially the component where the group was able to redirect and adapt according to the needs of the group. I imagine that happened more than once.

The willingness–and give-a-damn factor–to drive your own PD and growth as a group is inspiring.

Thanks, Brian. The collaborative writing was a nice way to wrap up some thinking about the professional development. It was an honor and pleasure to work with Rick and Jamilla on this, knowing that we were highlighting work of their STEM colleagues.