Do We Really Have High Expectations for All?

By Barbara Blackburn

By Barbara Blackburn

Do you have high expectations for your students? I’ve never met a teacher who said, “I have low expectations for my students.” The challenge is that we sometimes have hidden low expectations of certain students.

One year, early in my teaching career, several teachers “warned” me about Daniel, a new student in my room. During class, he certainly lived up to (really down to) the teachers’ comments. Despite my efforts, my expectations for him became lower, with the words “They warned me” echoing in the back of my mind.

Right from the start, no matter what anyone tells us, we have to be on guard to ensure that we keep high expectations in place for every single student.

Our behaviors speak loudest

Of course we may believe in high expectations for all the kids in our classroom but not translate those expectations into actions that support our beliefs. Instead, our actions may inadvertently undermine high expectations for all. When this happens, you can be sure students are quick to notice.

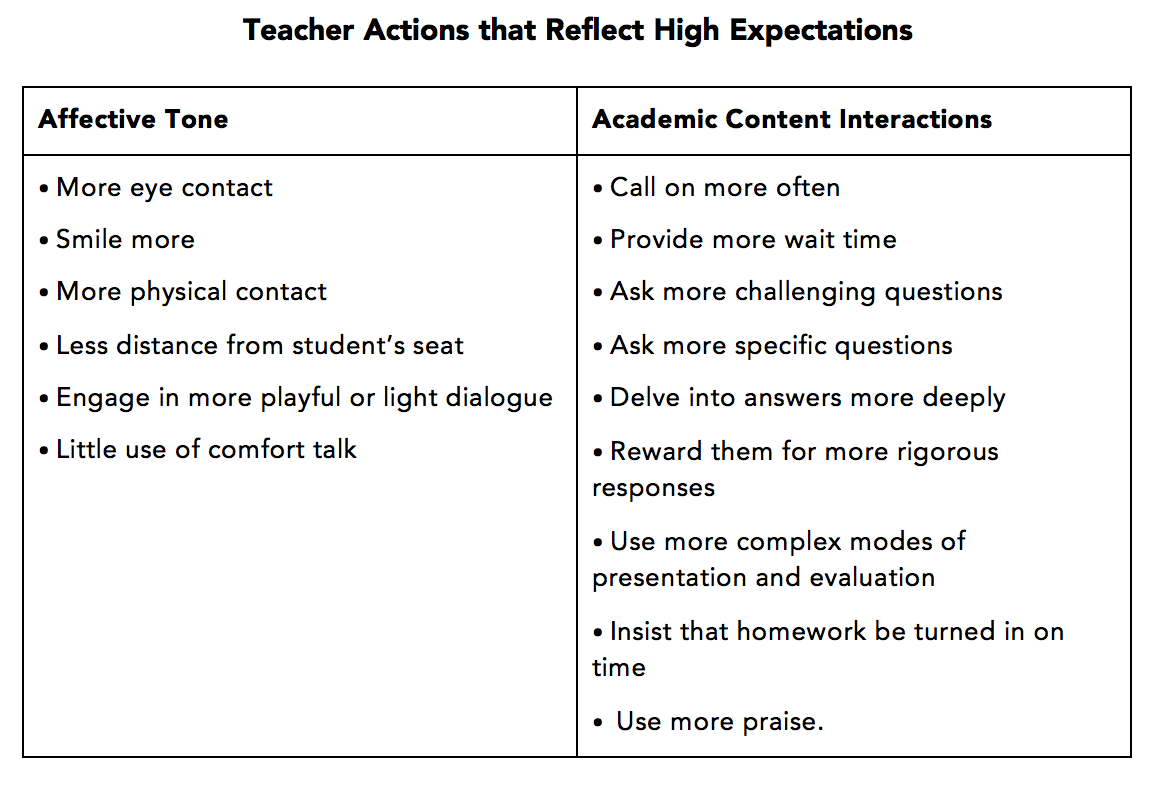

Robert Marzano has spent decades researching effective teaching practice. He and others have found that when we have high expectations, we treat students differently. When questioning students, we call on them more often, ask more challenging questions, provide more wait time, and probe for additional information.

How often do we fail to use these same strategies with struggling learners?

I know I made that mistake as a new teacher. Quinn struggled in my class, and nothing I did seemed to work. I ended up putting him in the last row of my classroom. As long as he behaved, I didn’t call on him or push him to participate.

Even though I said I expected all my students to learn, I didn’t really show that to Quinn. And he understood my message. One day, we talked about his performance in my class, and he said, “Why should I try? You don’t think I can do anything.”

That was an eye-opener for me. I was so focused on making sure he behaved and didn’t interrupt the learning flow that I didn’t challenge him. I was content to let him be a passive learner. My actions reflected subconscious low expectations.

The problem isn’t that we do not care

Another year, I had a similar situation with Clarissa. She was bright but had no confidence in her ability to excel. Her lack of self-efficacy caused her tremendous learning problems. She wasn’t willing to try to learn anything new or challenging.

I wanted to boost her confidence, so I provided easier work for her to complete. Instead of multi-step math problems, I gave her single-step problems. When we were reading, I allowed her to read easier books, many of which she had read before. I wanted her to feel successful.

I cared about her, but what I didn’t realize was that I wasn’t doing my job. I wasn’t teaching her to learn and grow—I was content to leave her in her comfort zone. By doing so, I also showed her I didn’t think she could do any better.

Once again, despite my comments to her that she could learn and that I had high expectations for her, my actions didn’t reflect my belief.

We have to match our beliefs about expectations to our daily actions in the classroom.

Which actions best define your expectations?

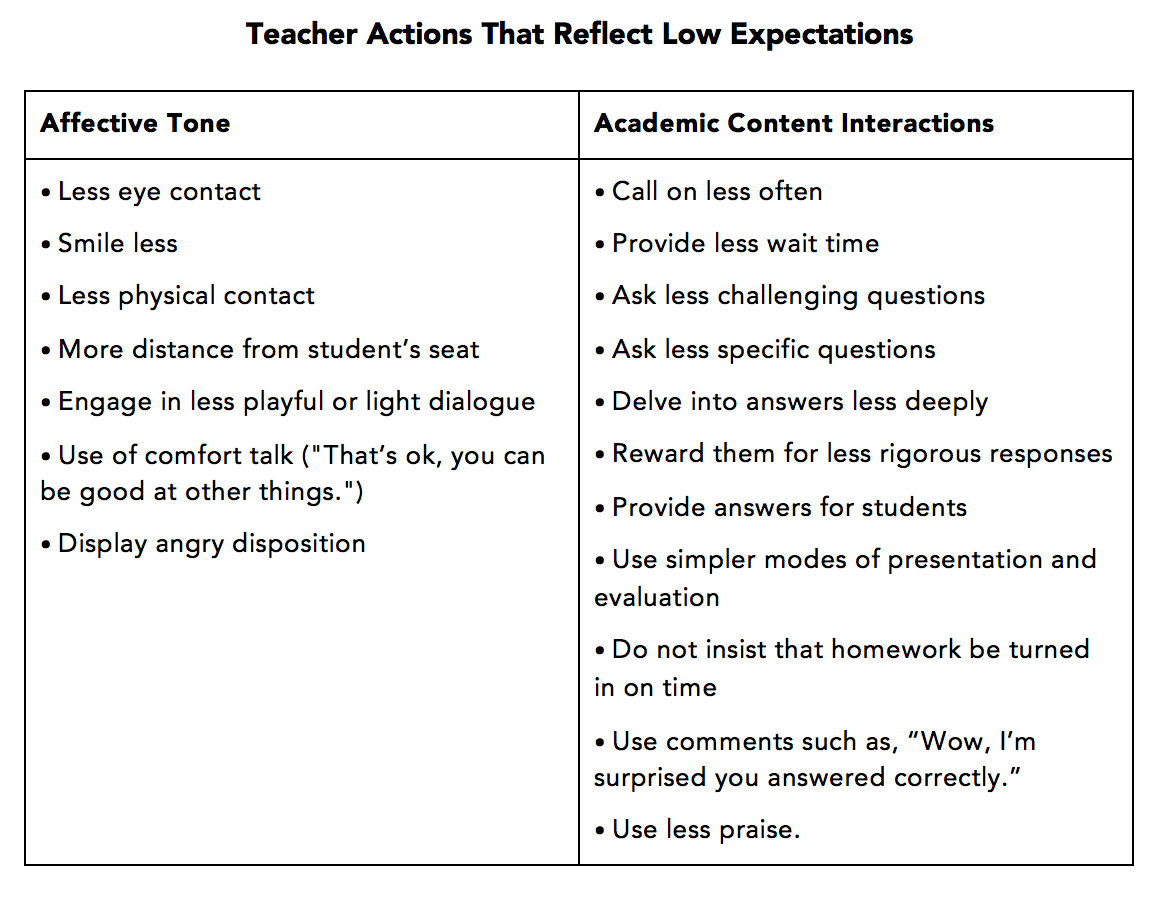

Many researchers have detailed specific actions we take that are reflective of low expectations. I’ve used Robert Marzano’s categories (2010) of our affective tone and our academic content interactions to provide a summary.

Motivation leads to achievement

Teachers need to have high expecations for every child in the classroom – and never more so than when our students have low expectations for themselves. It’s critical that we examine our beliefs to ensure they do represent a view of success for our struggling students. Then we must examine our behaviors closely, using the observational data from Marzano and others, to determine whether we are putting our beliefs into action.

By making our positive actions match our high expecations, we not only motivate our struggling learners, we help them achieve at higher levels.

Reference: Marzano, R. J. (September, 2010). High expectations for all. Educational Leadership, 68 1. ASCD.

I agree wholeheartedly. I teach in a “gifted” school, so called because of its historical reputation for high achieving learners, taught in a progressive, open atmosphere. We have students, however, who may not always fit the prototype; to those students I emphasize that I will hold them all to a high standard, and try daily to do that. Not unlike public schools, where some students fall through the cracks, even so called “gifted” students unfortunately find themselves in those same cracks, unless we fill those cracks.

Ms. Blackburn: Good evening. Years ago Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson spoke of “the self-fulfilling prophecy” or “The Pygmalion Effect”. In 1987 I used their model in my writings and in workshops. Best regards, Raymond J. Wennier

I find your thesis politically correct, but you ignore the expectations the student brings into the classroom and how the student’s behavior impacts other students’ expectations, creating a matrix of behavior patterns for the teacher to manage. An exceptionally bright student comports him/herself as such, especially in the midst of other, for example, 9th graders who read at 3rd grade level. It’s natural to expect more of this student, and less of the others. The question is, in this day and age of teacher evaluation based on student achievement, how is the student’s entering level taken into account?

Having high academic expectations, for all students, is not the same as having the same expectations. The student’s “entry level” is taken into account by measuring the actual growth of students from beginning to end point. Using high impact strategies increase the learning of all, including high achievers.

Lahigapes, I don’t disagree that we have students at differing levels, but it’s important to have high expectations for each one. What is clear from the research is that we ask lower level questions of our struggling students, when they are oftentimes capable of higher order thinking (not necessarily the same as a gifted student, but still higher order thinking). The majority of my teaching was with struggling learners who were reading 3-4 grade levels below where they were placed. What I found over and over again was that if I expected more of them, and provided appropriate support, they achieved at a higher level. I hope this provides clarification. Barbara

Thanks for this article. I think it’s also important to consider how institutional structures (e.g., tracking) communicate differing expectations to students and teachers as well as teachers’ actions. I really appreciated the specific examples and the use of Marzano’s charts, which I found to be very concrete reminders of how to express high expectations!

What about the expectations that students should be able to have of their learning experiences? If their teachers and schools aren’t designed to deliver on these “design criteria” then perhaps the teachers aren’t holding the students to the right expectations? (I’m intrigued to see what readers think of this short 3 min video – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K96c-TGnSf4)