Scaffolding Instruction: How Not to Learn to Ride a Bike

One of the most interesting parts about writing my book The Construction Zone has been watching everyone’s reactions when I tell them what it’s about. Usually it goes something like this: “Scaffolding?” “Yes.” “Hmm.”

When that happens, I’m never quite sure what people are thinking during the brief silence that usually follows. But after they recover, a few graciously reply with something along the lines of “Oh, how exciting!” or “I look forward to reading it” before changing the subject completely.

Still, some braver souls hazard a guess, following up with “Oh. You mean like . . .” and filling in the blank with their own take on scaffolding. When they do, everyone seems to have a different idea of what scaffolding is. Even so, ask just about any teacher if he or she scaffolds learning and most will likely say they do. Probe a little more deeply, though, and we might start to diverge on the finer details of our understandings of the scaffolding process.

Some may sincerely answer that they thought they did, but now that you ask, they aren’t so sure. It seems that when most of us are pressed for clear details around the concept, things start to go in a confusing labyrinth of different directions. Though many of us understand scaffolding as a way to support learning, our attempts to go deeper often leave us pensive. Faces scrunched up. Lips pursed. Convinced we do in fact know what it is, but struggling to word it concisely.

A deceptively simple definition

And if we’re having a hard time defining scaffolding, imagine how difficult it might be to have professional conversations around it—let alone actually do it.

Despite these complexities, scaffolding remains one of those perennial terms that has wound its way seamlessly into our collective psyche. Part of what makes scaffolding so tough to pin down is that it’s essentially based in a metaphor—the idea of supporting students as they build independence—and metaphors leave lots of room for interpretation.

On one hand, this versatility is helpful because it allows us to tailor the image in a variety of ways to fit our needs and growing understanding of the process. But these same benefits can also have the opposite effect, making scaffolding difficult to puzzle out definitively. It makes sense, then, that teachers might have varying ideas of what scaffolding is. With that in mind, my book aims to explore scaffolding by honoring its broad complexities while starting small.

I explore this multifaceted concept from a specific angle where scaffolded instruction characterizes a pattern of teaching that shifts the level of responsibility for the learning from the more knowing other (you!) to the less knowing other (your student). I expand on that idea as we work from a common definition that centers on five fundamental factors:

- a more knowing other supporting…

- …a novice in reaching…

- …some sort of educational outcome the learner could not yet reach alone…

- …in a constructive way…

- …that is temporary, steadily fading as the novice gets closer to (and eventually reaches) the intended outcome.

These factors seem straightforward at first, but when you take a moment to consider them more deeply, you’ll soon arrive at the thought that there’s got to be a whole lot more to it. For a more expansive view, we’ll need to move beyond this basic description.

Like our students, we need scaffolding from a more knowing other who believes that we can learn and thrive. We need someone like Terry Thompson, who believes we can transform teaching and learning ourselves.” – Donalyn Miller, from the Foreword

Scaffolding: Four Common Conditions

Beyond its basic diagram, scaffolding is an incredibly complicated process that would take volumes of books to explore definitively, and certainly no one diagram could ever make scaffolding easy. There are as many routes to independence as there are children in our classrooms, and no book could tell you everything you need to know about instructional scaffolding or what to do in every situation with every student and every goal.

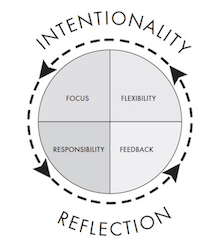

We can further fine-tune by considering the role we play in this process while directing our lens at four common conditions that apply to any scaffolding scenario, regardless of group size, educational setting, content area, instructional goal, delivery method, how it’s characterized, or even the learners involved.

These four common conditions are:

- Focus: Based in recursive and ongoing assessment paired with an understanding of the learner, we are proactive, teaching toward a clear, deliberate goal.

- Flexibility: Tethered to our focus, our scaffolds have a responsive, organic quality and shift with perfect timing to meet the specific needs of our learners.

- Feedback: Strong scaffolds exist and expand in an ongoing feedback loop that emphasizes and builds on students’ thinking so they can monitor how they’re doing and take the next, right steps toward independence.

- Responsibility: Our motivation in every scaffolding scenario is to place optimal levels of responsibility on the learner at every step in the process, so that our students are eventually independently responsible for the new knowledge.

Our scaffolds are strongest when we deliberately consider the influence of our work while practicing intentionality and reflection around these four common conditions. Let’s look at the first of these here: FOCUS.

Getting Focused: Identifying Relevant Learning Targets

I’m not a very athletic person. So it won’t surprise you that, each spring during middle school, I looked forward to my favorite P.E. unit: archery. Anytime I could avoid breaking a sweat, I was pleased.

Comfortable in that air-conditioned gym, I’d draw back my bow and carelessly point somewhere in the vicinity of the target. I didn’t have a clue what I was doing. I defined my success in archery by just hitting the target. Anywhere on the target was fine by me. Sometimes, by surprise, I’d actually hit the bull’s-eye. But if that happened at all—and that’s a big if—it had nothing to do with any premeditated strategy on my part.

Of course, they were so much better than I was because they practiced. They were considerably more invested in hitting the bull’s-eye than I was, so they spent their energies on what was most important to that end: improving their aim.

When we plan our scaffolds for readers and writers, it’s not enough to land somewhere on the target. Every time we draw back our instructional arrow and release it, it should fly straight and steady, landing solidly in the center of the bull’s-eye of the learning goal. With this in mind, we turn our attention to the first of scaffolding’s four common conditions:

Grounded in assessment, a clear, intentional focus is the driving force behind any scaffolding scenario.

One of the conscious teacher’s main priorities in the construction zone is to clearly articulate the instructional goal—first for ourselves and then for our students. Without a fine-tuned focus, our scaffolds fall apart before we can even get started, and we miss the bull’s-eye entirely. There is power in specificity.

How Not to Learn to Ride a Bike: Relevant vs. Related Instruction

The effectiveness of our scaffold is directly related to the clarity of our focus. But too often, what keeps us from moving our learners forward is the lack of clear vision on our part—we can’t see where we’re going. And when what we’re doing in the present isn’t connected to a clear vision, we’re left feeling depleted, frustrated, and ineffective.

This happens all the time. Consider how you learned to ride a bicycle. More than likely, you started out with training wheels and, after getting your bearings, blissfully rode along with them for some time. Then eventually someone—who seemed to know what they were doing—removed your training wheels, saying you were ready to ride a big-kid bike without them.

Reluctant, but trusting that you were, indeed, ready, you pushed off the pedal with one foot, ready to face the world without training wheels. And then you fell.

To be fair, your big person probably wasn’t aware of the mismatch. Parents have used training wheels for ages, so it made sense at the time. Here’s the rub:

If the instructional goal is to teach a novice rider to balance while riding, a much better option would be to remove the pedals and lower the seat so that he can touch the ground. In this way, he can develop his sense of balance by repeatedly pushing off with his feet and sailing forward, initially in small spurts but eventually in longer strides. Once his balance is developed, you can raise the seat, reinstall the pedals, and teach him to ride a real bike with ease.

This mismatch between a teaching decision and its goal illustrates the classic difference between relevant instruction and related instruction. When our aim is clearly focused on the bull’s-eye, we can say that what we’re doing is relevant to our goal. But often, we find that our instruction, though possibly related to what we’re trying to accomplish, isn’t directly relevant. In this case, training wheels are related to the broader goal of teaching a child to ride a bike, because we might use them to teach him to pedal and steer, but not directly relevant to balancing—our actual, intended goal.

When it’s all said and done, our arrow ends up somewhere in the vicinity of the target but not directly on the bull’s-eye, leaving the teacher and learner frustrated—if not a bit bandaged and bruised.

Keeping our aim true

We see evidence of this pattern in our teaching, too.

When we raise our planning to a conscious level, we’re able to make clear, informed decisions about exactly where we want to take our learners. Our aim must be calculated and precise. Once it is, we can tether the other scaffolding conditions—flexibility, feedback, and responsibility—to that aim. Our instructional arrow heads directly for the bull’s-eye.

Focus is holding the goal in sight despite all other distractions. This definition underscores two main qualities: establishing a goal and maintaining our direction toward it.

The Focus Phrase teaching strategy

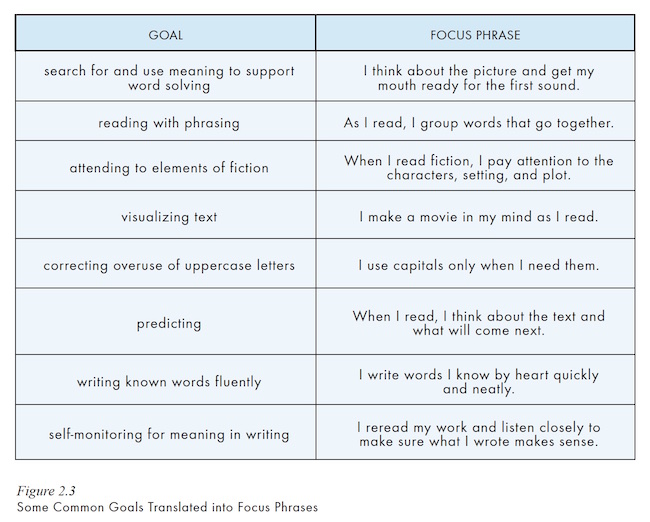

One practical technique you can use while getting focused is called a focus phrase. A focus phrase is a short, student-friendly statement of the goal that you and the learner repeat throughout the scaffolding process.

Since the phrase is repeated frequently, its language keeps the instruction and learning anchored to the goal throughout the lesson. The focus phrase is beneficial in three significant ways:

- It keeps the teacher focused on the goal during planning and delivery.

- It keeps the student focused on the goal throughout the instruction.

- It becomes the source for students’ self-talk when working independently, which eventually becomes part of their inner thoughts.

A focus phrase requires us to narrow the learning goal to its fundamental details and then to look at those details through our students’ eyes. Because of this, the process of crafting the wording for a focus phrase concentrates our thoughts and planning on exactly what we’re trying to accomplish and exactly what our learners will need to do. With this clarified understanding, we can move with greater precision toward the goal.

● concise and manageable,

● written in student-friendly language,

● based in a clearly defined goal, and

● maintains the integrity of the focus throughout the scaffold.

Once you’ve prepared your focus phrase, you can put it to work as a verbally repeated thread woven throughout your scaffold. You repeat it in your mind as you’re planning to keep your instruction intentional, you repeat it with your students as you work together to keep you both focused, and over time, your students take on its language, repeating it to themselves unconsciously and independently.

A focus phrase in action

To further illustrate this concept, let’s visit my friend Lauren’s second graders. Her readers were making meaningful attempts to pronounce words that started and ended with the correct sounds but were jumbled up in the middle (e.g., quickly for quietly). Together, Lauren and I crafted a focus phrase to support these readers in attending to sounds all the way across words:

“I run the bases across words as I read.”

This simple language drew on the analogy that when a batter runs the bases, he has to go in the right direction quickly, touching each base in order. As Lauren and I settled in for the group’s next guided reading lesson, I introduced the focus phrase:

TT: Guys, have you ever played baseball or softball?

S1: Yes!

S2: I haven’t, but I watch it on TV.

S3: I’ve never played that . . .

TT: Well, have you played kickball before? I think I’ve seen you play that.

S3: Oh, yeah . . . I’ve done that. Are we going to play kickball?

TT: Well, sort of. We’re going to run the bases across our words when we read. I’ve been listening in while all of you read, and I’ve noticed something I think I can help you out with. Take a look at this word [writes the word these on the whiteboard]. Yesterday when it was time to read, each one of you got to this word and said this word instead [writes the word those right on top of the word these].

S4: That’s wrong!

S2: Yeah. That one’s these and that one is those!

TT: Yeah, I know . . . they’re really close though and they both sort of make sense. It’s an easy mistake.

S3: Yeah . . . they’re almost the same.

S1: Almost.

TT: Yeah . . . almost. How are they different?

S4: [points to the middles] That one has an o and . . . the other one . . . it has an e!

TT: You’re right . . . it does. See, that’s what I wanted to talk to you about. You know how as soon as you hit the baseball or kick the kickball, you take off running?

All: Yeah!

TT: And you run quickly around the bases in order? And you touch each base along the way? And you run all the way home?

[All nod.]

TT: What happens if you forget to touch a base and you keep running?

S3: You’re out . . . it doesn’t count!

TT: Yeah! You have to touch them all or it doesn’t count. You have to run the bases. It’s the same way when you read words. You have to go in order, touching each part of the words with your eyes and making sure what you say matches. You run the bases across words when you read. Everybody say that: “I run the bases across words when I read!”

All: I run the bases across words when I read!

TT: Yeah. That’s it! Let me show you what I mean . . . look here at the words those and these . . . if you got to the word these and read those instead – you missed a base with your eyes. You touched first base [points to th], skipped second, and then ran all the way home [points to s and e]! If you don’t touch all the bases with your eyes, it doesn’t count.

S3: Yeah. It doesn’t count . . .

TT: Watch me run the bases across this word while I read it . . . [continues to model]

Focus phrases work across the grades

As you review this exchange, notice how frequently some form of the focus phrase comes up. This is intentional. The main goal for the focus phrase is that after hearing it and repeating it frequently, the concept eventually becomes second nature for the student—taking advantage of the concept that the learner eventually internalizes the language shared during interactions with the more knowing other (Vygotsky 1978; Berk and Winsler 1995).

Whatever age the students may be, the more the focus phrase is repeated, the stronger the focus becomes and the more likely learners are to take on the language for themselves and, over time, incorporate it into their thinking.

As the group moved from modeling to shared support and eventually to independence, Lauren and I were on constant lookout for authentic moments where we could prompt, reinforce, or give reminders for students to run the bases across words while they were reading. Within a handful of lessons, all but one reader was finding success attending to sounds across words.

Focus phrases can be crafted across grades K-8, for individual, small-group, or whole-group goals and can support every stage of the learning process.

I find this method such a valuable tool for keeping me and my learners on track instructionally that I often write focus phrases at the top of my lesson plan or near the individual student’s name on my conferring clipboard.

Having it right there where I can see it reminds me of my focus and keeps me on track throughout the scaffolding process.

Adapted with permission from The Construction Zone (Stenhouse, 2015).

Thompson is an evangelist for graphic novels as “real reading.” He has served as a reading interventionist, a classroom teacher, basic skills teacher, Reading Recovery teacher, and literacy coach. He holds a master’s degree in psychotherapy and cognitive coaching.

Such good help! For sure I will use these ideas to help all my students, so we can improve our teaching- learning process in the English language. Thanks, Terry Thompson!

From Rondônia, Brazil