Crafting a History Skills Scope & Sequence

A MiddleWeb Blog

As we look to the start of the school year, it’s also a good time to look to the future: If you could design your ideal history/social studies program from scratch, what would it look like?

As we look to the start of the school year, it’s also a good time to look to the future: If you could design your ideal history/social studies program from scratch, what would it look like?

Maybe you would have the department centered around Project Based Learning, or perhaps open the walls, get modular furniture, and mix the grade levels…maybe take the students’ research online and expand the classroom beyond the classroom.

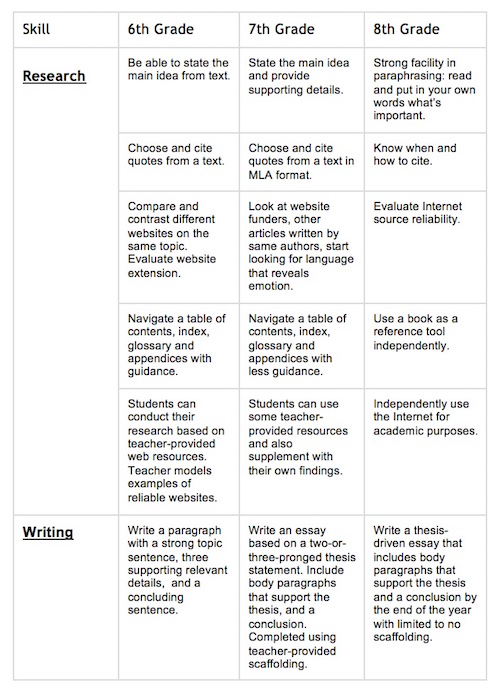

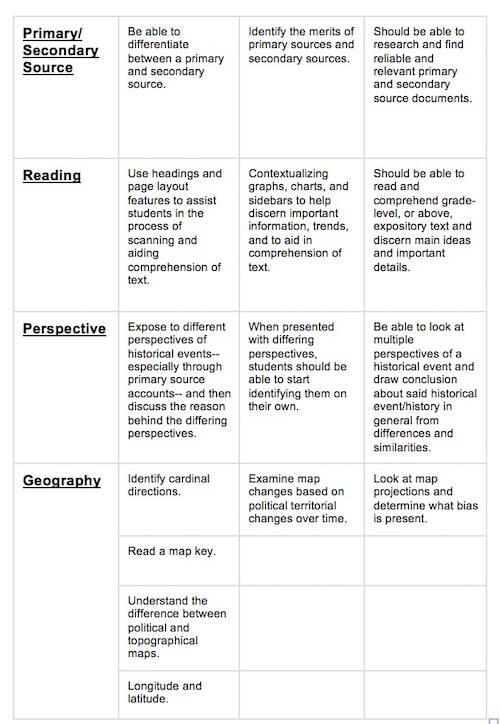

We would love to do many of those things ourselves, but for the purposes of this examination, we looked at what, from our perspective, would be the ideal skills for a social studies department to focus on. Also, if we were to spiral those skills through 6th, 7th, and 8th grades, what would that look like?

Our Decision to Focus on Skills

We both teach in independent middle schools in greater Los Angeles, and there are certain high schools that the majority of our students attend after they finish our respective programs. We have been in contact with the high school history departments, wanting to know where our former students appear to have academic strength, and in what areas they could use some more preparation for the demands of a high school history program.

And it’s not just about high school: when students complete their academic careers and forget what date the Constitution was ratified, they can quickly look that up. What we need to instill in them are the skills that Google won’t provide.

Impact of Common Core

Common Core has helped spark a deeper conversation about what skills — language, writing, research, reading, geography, historical thinking, facility with primary sources — that we want students to leave our classroom owning. We’re finding this to be true in both public and independent schools.

So we looked through our curriculum to see what we were expecting our students to be able to do by the end of eighth grade – and went backwards from there.

► What research were we expecting the students to do independently or with their teams?

► What kind of reading comprehension level were we expecting them to have achieved?

► What level of writing were we asking for? What level of scaffolding would be necessary to help students achieve this?

► And most importantly, what would be a developmentally appropriate timeline to expect students to be able to adhere to as they grow these skills?

The “Never Final” Product

What we developed is in no way a final product, and honestly, there may never be one. And why should there be? Teaching is always a work in progress.

We look at our skills curriculum as a living document that we will constantly revamp. We’ll do fine-tuning after each unit is taught, and look at the curriculum on a macro evel at the end of each year.

The skills curriculum is also something that we will need to adapt to the needs of our particular students. It is reasonable to expect different timelines from an honors history class than from a class consisting of many students who struggle academically. That being said, we do hope that by the end of 8th grade, all students will be able to meet expectations for skills associated with the study of History.

Also, we currently have map skills based in paper maps. It is quite possible that next year we may decide, for relevancy’s sake, that we should be explicitly teaching students to use tools like Google Earth or a different map/geographical skill as well.

Things We Had to Consider

Every school is different. We work at different independent schools right now, and though they are similar to each other, the students do have different needs. The writing style at one school might be different than another, depending on whether that school ascribes to a particular writing program or philosophy.

Additionally, the chart that follows presupposes an availability of technology that is not accessible to all students (though it should be), and so adjustments would need to be made on that front as well.

Stretching the Future

The 21st Century is a crazy time for education, and educators are always talking about preparing our students for jobs that don’t yet exist. We have both thought about and written about the ways that technology and changes in education affect history instruction specifically.

This was one of those times where we again found ourselves stretching our brains into the future, trying to imagine what a history department should look like now and as we go forward, not what it should have looked like in classrooms of the past. What is the future of history skills?

Here’s our plan:

Want a copy? Download our History Skills Chart.

What are we missing? What skills would you focus on in your ideal 6-8 social studies department?

Extremely well created matrix!

teaching students the skills associated with group work/collaboration

Thank you for sharing.

We just had this meeting two days ago.. One thing I see missing, is learning and using vocabulary. Especially government, geography and test taking vocabulary,include these in your teaching and reuse them throughout the year. I love the document.

It’s the eternal dilemma: Do we expose our young learners to as much of the wonderful history content that we know and love in one school year, or give ’em as much historical detail as we can while building and practicing their reading, writing, research and speaking skills so that they can use these skills more effectively in their high school social science courses? I am leaning more towards the latter despite my frustration at not getting to the Civil War these past few years. :0(

Excellent blog post. We are having similar discussion at our school.