Unlock Learning by Improving Oral Fluency

Of all the ways you can improve learning in your school, the Number 1 way is to strengthen students’ speaking and listening skills and habits.

Why? Let’s start with listening. Probably at least 80 percent of what students do in any given class involves listening. And by “listening,” we mean listening comprehension.

Whether listening to their teacher, their classmates, or some form of media, students must process and comprehend a lot of information aurally. If they don’t listen well, they won’t learn well. Therefore, we must train them to listen effectively.

Along these same lines, we must also teach them how to speak effectively. Obviously, speaking is an essential life skill in and of itself. But it is also crucial because of its impact on learning. Active participants learn more.

Although it might sound really obvious, this truth took me a while to absorb and was finally brought home to me by one of my favorite students, Jairo.

How Jairo helped me raise my expectations

In retrospect, I think he was stuck in a “fixed mindset” (a la Dweck, 2006). He believed that he wasn’t good at English and that was that. Then one night around 6:00 PM, while I was working with Jairo and a few other students on research papers, Jairo had a breakthrough: he was excited about his topic and had figured out how to explain it. He worked really hard and wrote a fabulous paper.

A few days later, as I handed back the papers, I told everyone what a great job he’d done. From that day forward, Jairo opened up and began to engage in class discussions more assertively. One day when I praised him for his contributions to the class, he admitted, “I feel like I’m getting more out of the class when I say things.” Indeed, he was. The quality of his work overall improved.

If you ever feel like you don’t want to push a shy child to speak up in class, think about Jairo. For far too long, I went easy on him, and he could have learned more if I’d expected more from the start.

In many schools, incomplete thinking is the norm

Effective speaking is also important because—along the same lines as writing—it demonstrates how much you comprehend. If you cannot articulate your thoughts coherently, it could be because you are not thinking clearly, you lack information, or you do not understand something. Or it could be because no one expects you to express your ideas fully, so you’ve developed a habit of expressing incomplete thoughts, which would also block deeper learning.

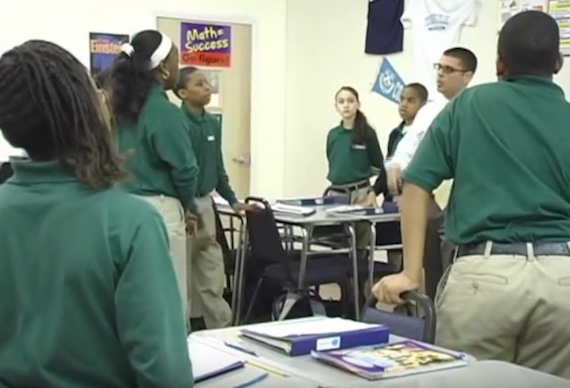

Unfortunately, in many schools, incomplete thinking is widely accepted. Walk into a classroom in almost any building, and more often than not, you’ll see a teacher calling on students who respond with incomplete sentences.

It’s a common occurrence for three reasons:

► Teachers want to keep things moving, so they often accept brief responses;

► Teachers’ questioning techniques solidify into habits, and

► Most teachers don’t understand the impact of this particular habit.

The truth is, supporting fragmentary responses undermines everything you’re trying to teach because it derails the comprehension process. When students don’t explain their ideas with complete sentences, it may signal that they haven’t reached the level of inference and explanation; they may not comprehend the topic, issue, situation, or point as fully as we would like.

High standards for discourse in your classroom will boost not only fluency but also comprehension. In his book Teach Like a Champion, Doug Lemov asserts that “the complete sentence is the battering ram that knocks down the door to college.” I would also add, “And it’s great low-hanging fruit for teachers who want to help students improve their reading and writing.”

The oral practice of expressing complete thoughts translates into more penetrating reading and more coherent writing, plus it teaches other students (who hear these complete explanations) more in the process. It’s a win-win-win.

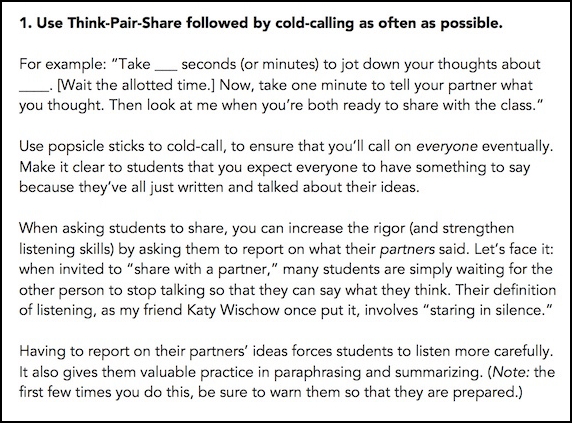

In Part 2 of this discussion on listening and speaking skills, I share 12 ways that teachers can address this and other oral fluency issues. Curious? Here’s Tip #1. Watch for more!

• Lemov, D. (2010). Teach like a champion: 49 techniques that put students on the path to college. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

• Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Random House.

In her next post, Sarah Tantillo shares a dozen ways that teachers can help students strengthen their speaking and listening skills.

______