How to Fill Your Class with Joyful Learning

If you asked students about their most memorable learning experience years after they’ve left a school, what would they say? Many would be hard pressed to recall even one academic learning event that permanently impacted them in a positive manner.

Schooling is often so regimented, test obsessed, and disconnected from students’ lives that the deep learning and joy that motivate our learners are rarely at the forefront. We can and must change that for students, and for teachers too. Here’s how.

1. Make the challenge just right

Begin by engaging hearts and minds in meaningful and challenging subject matter. If students care about the work and we provide them excellent and sufficient resources, demonstrations, support and guidance, they will advance as readers, writers, and thinkers and have good test scores too.

Not only that. Through advocacy and clear communication, students learn that even young citizens can have agency in their lives and positively impact the lives of others.

In recent work in a diverse school, my colleagues and I connected reading and writing with environmental sustainability and the responsibilities of citizens, an important topic that spanned the social studies and science curriculums and real world concerns. Specifically, middle graders focused on a vital lake in their community that has been deemed as threatened. Many towns, families and businesses in their region depend on this lake for clean water, fish, recreation and more.

We framed our work around these big questions:

- What’s happening to the environment to threaten the lake?

- What are the main causes? What are the results?

- What is being done—and what can we do—to restore the environment?

- Why does all this matter?

Once we decided what we wanted students to know and be able to do, we worked backwards from there.

- What would we need to do so students would meet success?

- What information and supports would we need to provide so students could work, for the most part, independently?

There is no formula or packaged program for the kind of work that engages kids and changes their view of what’s possible – for themselves and for others.

The work has to be challenging and relevant; the teaching and related assessments need to be responsive to students’ ongoing needs, interests and culture; and we have to do sufficient frontloading to give students the background, tools, and experiences that make it likely every kid meets success.

2. Frontload the learning challenge

Frontloading includes everything we do before and during the learning process to ensure students can work successfully and as independently as possible. Frontloading may include but is not limited to:

- Immersion in a topic or genre (for example, through reading, viewing, examining, and/or listening to related texts, videos, experts),

- Demonstrations and thinking aloud,

- Shared experiences,

- Questions that spark curiosity and deeper thinking, and

- The gathering and charting of useful information.

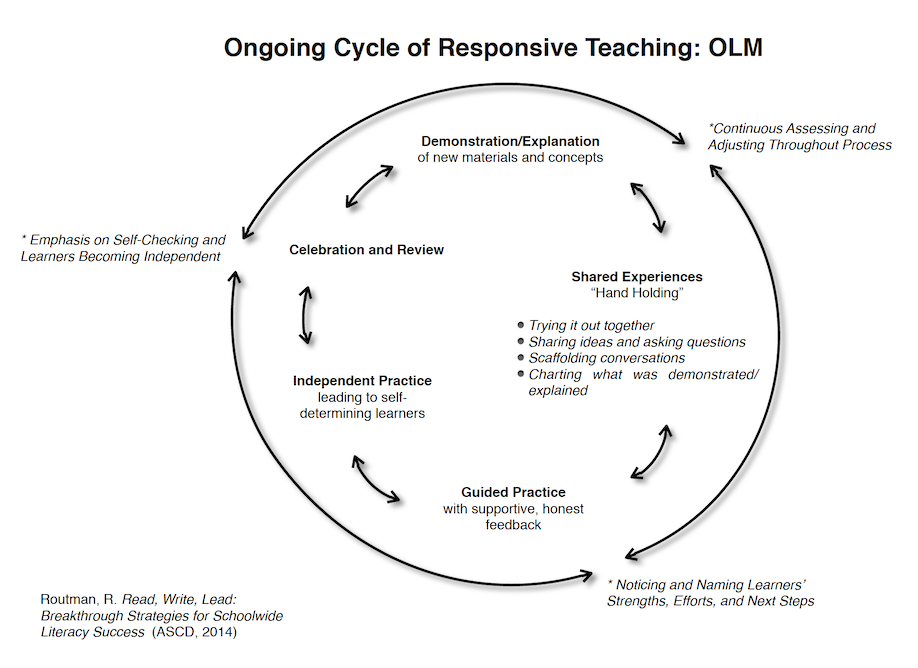

Most frontloading occurs as an integral part of applying an Optimal Learning Model, the foundation of all my work (Routman 2003). The OLM represents an ongoing cycle of responsive teaching where the ultimate goal is self-determining learners who self-monitor, self-direct, and – ultimately – set their own worthwhile learning goals. Here’s an infographic (click to enlarge):

The OLM approach deepens the learning experience. While it is based on the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model (Pearson and Gallagher, 1984), where it differs is in the emphasis. The gradual release model emphasizes decreasing support for the learner as s/he gradually assumes more responsibility for the learning. The OLM’s focus is always on the learning that is taking place.

The Optimal Learning Model ensures that learners are not just able to read and write well but are able to talk about and explain their thinking. To that end, teachers provide expert and explicit demonstrations, explanations, shared experiences, and time for guided practice. Throughout, we continuously assess – most often through questioning – the learner’s level of understanding.

As needed we reteach, regroup, modify the instruction, and/or provide additional resources, support and guidance. Then, as the learner demonstrates increasing understanding, s/he is encouraged and expected to assume more responsibility for the learning. The learner becomes more self-directed and is able to figure out problems and solutions with minimal guidance.

If curriculum and standards aren’t leading students to become learners who are enthusiastic, intellectually curious and critical thinkers, why bother?

This is very important: the OLM is not about teaching isolated standards, trivial information, or the implementation of a mandated program. If curriculum and standards aren’t leading students to become learners who are enthusiastic, intellectually curious and critical thinkers, why bother? Of course, curriculum and standards are fundamental considerations; however, our first commitment must always be to the best interests of our students. (Read more about OLM here.)

3. Slow down the teaching to hurry up the learning

Our study of the local, increasingly threatened lake led to finding information through books, articles, videos, websites, interviews with experts, field trips, and deep discussions about climate change, the impact of farmers’ use of pesticides, declining wetlands, crops and run off, and a heightened environmental awareness that led to actions on a crucial issue.

Student advocacy took the form of persuasive letters to the school community, families, and government officials. These well crafted letters clearly defined the problem, offered recommended actions, and ultimately led to fund raising efforts to help clean up the lake.

It was the four weeks of frontloading, which included demonstrations and shared experiences in all aspects of our writing process – along with sustained time for practice – that made it possible for all students to be successful.

How did we slow down and front-load the learning? We used three key strategies:

► Demonstrations

Either we show the learner exactly what a “good one” looks like and sounds like or we explain the task or goal in a comprehensible way. We may think aloud as we read and write in front of our students, show our back and forth reasoning and revising process in writing and reading – including our struggle – and/or give examples and criteria of what the expectations are for “the work.”

However, just doing and showing are insufficient. We always need to check for understanding to make sure students “got” our demonstrations. See these “Must-Know Tips for Effective Demonstrations” for some proven strategies and details on that process.

► Shared Experiences

Don’t rush through shared experiences. This “we do it” part of the Optimal Learning Model is crucial for student readiness, competence, and confidence to do “the work.”

► Guided and Independent Practice

Make independent reading and independent writing – with sufficient choice and useful feedback built in – the number one priority and work backwards from there. Most important, if students aren’t given sustained time every day to read and write whole, meaningful texts, they won’t improve much as readers and writers.

All the frontloading makes it possible for students to problem solve, monitor their work, self-check, and successfully read and write on their own or as part of a collaborative group and, eventually, to become self-determining learners.

For example, the students who focused on their local threatened lake not only wrote persuasive letters to various stakeholders, they also explored resources beyond what we provided and continued to learn new content and expand their role as responsible citizens. Several took the initiative to write to the Minister of Conservation and Stewardship urging the government to do more.

4. Celebrate the Learning!

Name and notice each learner’s strengths and efforts. Such genuine celebration is at the heart of excellent teaching and leading. When feedback explicitly focuses first on what the learner is doing well before moving on to what may need improvement, students – and teachers too – are much more likely to leave a conference, conversation, or task with the energy and will to “do the work,” take risks, be part of a collaborative team, and raise expectations for what’s possible.

Great teaching and joyful learning

are the same everywhere I go

In more than four decades working in underperforming schools in the U.S and Canada with large numbers of minority students and second language learners, I have found that one constant is kids (and teachers) are the same. They are all eager to learn important things, and most are able to comprehend at high levels when we make the work interesting, relevant and doable and when we celebrate every learner’s strengths and efforts.

What are you doing to deepen learning in your classrooms and make it joyful for everyone?

Regie’s current work involves week-long school residencies where she demonstrates effective reading and writing practices in diverse classrooms, coaches teachers and principals, and facilitates ongoing professional conversations, all as a catalyst for sustainable, whole-school change. Visit her website.

Terrific article, Regie. This is an important topic that you can’t write about enough. I especially appreciate the advice of slowing down the teaching. In our fast-paced schools that always seemed to be driven by unnecessary outside forces, your words are timely.