Extreme Differentiation in Current Events Class

A MiddleWeb Blog

If one student can’t get enough of foreign policy accords and another wants to read only feel-good stories about human nature, what could I do for each of them in class? How could this attention play out in their lives, now and in the future?

I started thinking along these lines of “extreme differentiation” after my post about wanting to transform students’ awareness of current events into action.

To begin, I looked over my students’ responses to a short-answer question from last year’s final exam, which asked them: “What is your stake in current events? In other words, why do you care about current events? Which kinds of articles most pique your interest, and why?”

Here are some dreams for each of them.

Case #1: America as “police officer”

Rithik seized upon the idea of America as the “world’s police officer,” a topic we had discussed over the course of the year.

“The articles that are able to fully grab my attention,” he wrote, “are about how America’s involvement with the world’s problems always seems to affect the final outcome. For instance, America has recently been attempting to make a nuclear deal with Iran, for the safety of the world. Although America should arguably mind our own business, I do find it interesting that we have enough power to settle numerous disputes. The way that we exercise that power is significant to our image.”

In an ideal world, I would love for Rithik to interview an editorial writer or attend a speech by the Secretary of State on nuclear weapons. He could read primary documents on the history of nuclear deterrence and disarmament and then write a policy paper or letter to the editor on how he thinks the U.N. should decide who is allowed to have weapons.

In my ultimate fantasy world of learning, he might sit in on a Congressional committee’s deliberations on Iran’s nuclear program.

Case #2: Who should have nuclear weapons?

Sparked by a unit on the atomic bomb, Evan asked how the United States gets its mandate over other countries:

“I find it interesting how we believe we can help other countries, when we are barely managing ourselves. Most recently, we are trying to prevent Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons…. We are a country who dropped two atomic bombs on cities [Hiroshima and Nagasaki], so aren’t we the ones people should be most worried about?”

Evan could focus on the history of anti-nuclear protests and maybe even find a peace rally to attend. He could write a letter to the president about the relative budget merits of nuclear spending versus domestic priorities, reading Dwight Eisenhower’s “Cross of Iron” speech in the process. He could pick one of those other priorities, such as health care or immigration, and attend a city council or state assembly meeting about it.

Case #3: Making the punishment fit the crime

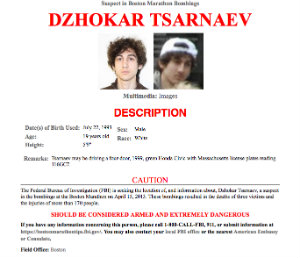

After first admitting that, “when I come home from school, current events is not the first thing on my to-do list,” Libby went on to write that the trial of the Boston Marathon bomber from 2013 intrigued her.

“This event happened about two years ago, and only a few weeks ago did the court decide he would be sentenced to the death penalty,” she wrote. “Yet some of the victims wanted him to be sentenced to jail for life. Then I realized why – they wanted him to have a longer lasting punishment.”

Case #4: Women’s rights around the world

Finally, Sasha connected women’s rights in the past to our present day:

“When studying history we speak in the past tense as if some of these events are over; some are but many aren’t. For example, I very recently read that only now will women in Iran be allowed into sports stadiums. Many people will forget that all over the world and still in America women have not won equal rights…. I will one day be affected by the unequal wages for equal work so it is important to learn about women’s rights issues now.”

To research her interest in social reform, Sasha could attend an event sponsored by Rock the Vote or the League of Women Voters. She could work for a political campaign with a focus on gender equality. She could also follow a female representative or Senator for the day, asking about her views on equal rights – whether women have come far enough and do not need an Equal Rights Amendment, or whether there is still work to be done.

Toward curiosity for all

This year I hope to do a “thought experiment” for each student at least once, focusing on how to expand their curiosity – both about current events and historical questions – in a way that speaks to each learner as an individual.

A few strategies that could make all students more curious and invested are:

- Researching the history of a protest movement

- Attending meetings or speeches on a controversial topic

- Writing letters to politicians or activists

Each of these ideas is feasible, even without a massive long-term project, and could lead to students becoming more informed citizens.

How do you differentiate to engage students’ curiosity in your own history classroom?

Image credits:

John Kerry – Reuters

Sister Megan Rice – Washington Post, Linda Davidson

Wanted poster – FBI

Lilly Ledbetter signing – White House

Feature image – AFP/Getty Images, Mandel Ngan