Helping Students Learn to Cite Their Sources

A MiddleWeb Blog

When I first started teaching writing in history class a number of years ago, I was totally focused on the students just getting their ideas out and being able to write on historical themes.

I wanted them to be able to internalize the basic structure of an argumentative essay, make an argument, and back it up. So I provided the sources. If the students used, say, the Constitution summary I provided the class, or a excerpt from Howard Zinn or Paul Johnson, or something found in their textbook, that was okay. So long as we used the source in the current unit of study and students didn’t go elsewhere for information, I didn’t worry about citations.

I was already asking them to do so many things – create an argument, find details to back it up, and write in a structured essay format. Creating citations on top of that was too much, I thought.

“Just back up your ideas”

This approach to historical writing worked quite well for a few years. Students were using the discrete materials from class to formulate a historical argument, back up their ideas, and then write four or five paragraph essays.

Meanwhile, in English class, the students were being taught MLA format for quotations. Whenever they insisted on using quotations in their writing, I would require them to cite the source of the quote using the same method they used in English class.

But I was still a long way from requiring both in-text and end-of-text citations. Sure, when they did a research project, I would make them turn in a list of “source websites,” but it was still nothing formal.

“Wait…Do you know which ideas are yours?”

Then I had an epiphany. One year I introduced a new essay at the end of a unit that hadn’t previously had an essay assessment. It seems that that unit didn’t have enough approachable text, because when it came time for the students to write their papers, instead of the usual details used to back up ideas – and these details looking more or less familiar across the board – I was getting mostly ideas born of Internet research.

I had previously required students, if they DID use the Internet at all, to cite their sources, but no one really ever resorted to online investigation. There was enough material from class to draw on. Until now.

So for this new essay assignment I was getting weak paraphrasing, with or without citations. With no accountability for where they were getting their ideas, students WERE backing up their thesis, but not crediting where they found the information. Before they went to the Internet, we all knew where the information came from, but now more accountability needed to happen.

Time to teach citations

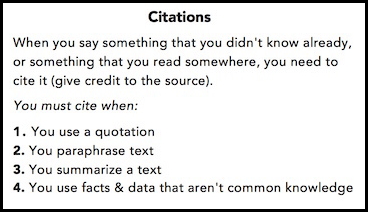

I resolved that for our next essay I would explicitly teach them about citations. First and foremost, I wanted them to understand that the most important thing about citations is this: If it isn’t your idea, you need to cite it. No matter what.

This key understanding is more important for them to grasp than any particular citation format. I’ve written citations in many styles: MLA, APA, Turabian, you name it. And I still have to look up the exact formatting on the OWL Purdue site EVERY TIME. Whatever the style preference may be, the rationale never changes. Historians always credit the work and thinking of other historians.

You won’t be surprised that we struggled for awhile

My new goal became teaching the students that they must cite. If it isn’t common knowledge, if they read it somewhere, if it’s a quote, they MUST cite. I tried to make our citation method a bit simpler version of MLA, because what I really, really wanted them to figure out was that they needed to cite, not necessarily just memorize the specifics of citation styles.

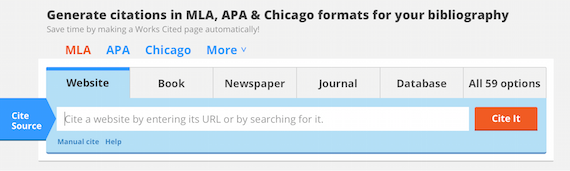

The first time I implemented both in-text and end-of-text citations, students struggled with formatting. I made a flipped classroom video to help them review at home as well as a “cheat sheet” to walk them through it. Additionally, students could choose to use a resource like EasyBib (which, can I say, I really wish had been around when I was writing my thesis!) to help. (Also check out MyBib, a free option that’s a GoogleApps choice.)

More important, students struggled with the concept of citing someone else’s idea. Quotations they understood. When they used a quotation, they totally got that they needed to cite their source. However, once they’d paraphrased another writer’s text, they didn’t really see why they would need to include them as a source. I didn’t expect this disconnect, and it was a concept that I needed to mention over and over: a writer’s original thoughts are his or her “intellectual property,” whether or not we present them verbatim.

“Common knowledge” was another issue that arose (one I am sure many history teachers will understand). As we teach a unit, certain ideas start feeling like common knowledge – something the students have always known. For example, during our unit on the westward expansion of the United States, students might say: “Well, I just KNOW why the U.S. got the Mexican Cession after the Mexican American War in 1848,” and we would have to talk about how they came to “know why.”

Citing class materials was another issue that came up: how do the students cite class handouts and teacher-shared notes? For in-text citations, I asked them just to put (Class Handout, “Expansion Overview”) or the like as a simple style for these things.

Again, the idea wasn’t just that they were able to cite perfectly according to MLA style, but that when they used an idea from a specific person or source document, or information that wasn’t common knowledge, they understood that they should cite a source.

In-class writing: putting it together

Now it was time to try something new. Over two days in class, I had my students work on a four paragraph, thesis-driven essay: What was the main cause of the Civil War? In addition to all the usual things I required (intro, thesis, body paragraphs with relevant supporting details, and conclusion), I also required in-text and end-of-text citations.

While the students didn’t get the proper formatting 100%, most students realized when they needed to use a citation. And if they needed extra help I was able to support them in Google Drive, where they post essay drafts as Google Docs and can get one-on-one collaborative help.

I’ve been pleased with the results of my citation lessons. I think I am sending stronger kids to high school this way. Will all of the students memorize the rules for MLA formatting? No. But they will realize that when they get an idea off the Internet that backs up their thesis, they need to cite their source. And they will have a basic idea of how to do that. That is a skill they will use the rest of their lives.

Do you require students to cite? At what ages? With what method?

From this high school English teacher, bless you for having your students write at all, much less doing all this difficult work of citations. I know History teachers feel the pressure of having to cover content, but to resort to rote memorization and multiple choice is no way to go. History is an interpretation of what happened and relayed in writing, so having your students interpret, write, and cite is having them be historians. Again, thank you for having them write!

I am an eighth grade ELA teacher at Hopkins Middle School located in Hopkins, South Carolina. I use a combination of Quote Sandwiches with R.I.C.E. for my students’ citations. Each week, I review the science and social studies lesson plans of my teammates and construct four higher order thinking (Levels 3 and 4 from the Depth of Knowledge Question Stem chart) content-based constructed response questions based on work that the students did during the previous week. (I usually just pull the essential questions that those teachers placed at the beginning of each lesson)

As we are working within a blended learning environment, (our students receive their laptops on Monday, September 28, 2015.) we rotate within the classroom three days per week. One of their “stations” is Content Response Questions (CRQ Station) where they bring either their social studies or science textbook on alternating days and work with their partner to answer the c.r.q. within the 12 minute rotation time. Since the work is basically review from the previous week’s content time, they have a familiarity with the content and be more focused on evidence citation from the text as oppose to getting “caught up” on the content reading for my less proficient readers. While they only have two questions to do–one for classwork and one for homework, they enjoy “scamming” me, the teacher by getting both done and sharing their information. Cooperative learning–win-win Whoo Hoo!

The Quote Sandwich and R.I.C.E. formats can be found by “Googling” but here is a brief at-a-glance summary below.

Quote Sandwich and R.I.C.E.

Quote Sandwich: http://www.deanza.edu/faculty/leonardamy/The%20Quote%20Sandwich.pdf

R.I.C.E. PPt: http://www.vrml.k12.la.us/khs/curriculum/RICEslideshow.ppt

1. Students turn the question into a statement beginning with a signal phrase such as, “According to the author”, “The author states,” or “According to the article”, etc.

2. They use a quote from the text to answer the question. This quote is followed by the author’s name and page number in parentheses.

3. They use another quote from the text to highlight why the topic/response was important. (If the response is found on the same page of the textbook (Ibid) is placed in parenthesis after the quote.

4. Students end their response by stating “In fact…” and inserting a germane quote again followed by Ibid.

This process begins during the first week of school in order to get the students acclimated to bringing an additional textbook to class on Monday’s through Thursdays and more importantly being conscious of how to properly give credit when words and ideas neither come from nor originate from their minds,

Thank you so much! Loved it! So helpful!

God Bless you for mentioning this! My students will have a much easier time inserting quotes and citing their sources.

A specific example of a citation or citations would’ve been more helpful than the above narratives.

Hi Martina, thanks for reading; hope this helps:

These are the simplified MLA citations I asked my students to do; they could also go more complete and use EasyBib, if they so chose:

In-Text Citations

Book:

(Lastname, pagenumber).

Example:

(Johnson, 55).

Website:

(History Channel, “George Washington”).

Works Cited Page

Citing a book:

Lastname, Firstname. Title of Book. City of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example:

Johnson, Paul. A History of the American People. New York: Harper Collins, 1997.

Citing a website:

“article name.” website name. date of access. (url)

Example:

“George Washington.” Historychannel.com. May 5, 2014.

Excellent!!!

As a former high school English teacher (all four grades) and now a high school librarian, I cannot express just how fabulous it is that you teach your middle school students how to properly cite borrowed information. Unfortunately, at my current school, students in junior high are not taught how to properly cite information; therefore, the 9th grade English teacher must start from scratch teaching her students the process. How oh how then can I approach the subject with the junior high English teachers on the importance of learning the process early to better prepare students for high school and college? I certainly do not want to insult anyone or step on toes, but apparently there is a critical need for such instruction.

It is a part of our standards in Middle School and in High School. When you have students with RTI and IEPs that have it mandated that they must receive information in chunks, yes. Yes, these small steps, that most of us were forced to read out of a Harbrace, and find for ourselves are wondering, what is wrong with that method, they have changed the rules/

We have to simplify things. Differentiate. Do I agree? I love my job!! I think I am not the dumbest person in the world, but I am not the smartest either, but we are creating a group of kids that cannot think and want us to do things for them. I am not a spoon feeder. I make them do more than my coworkers.

I have a possibly dumb question…why are does it seem like many people are against teaching the Chicago Style to students in History, since that is what historians use? I have taught that for many years which seemed to help my students who had trouble with MLA to get the idea that citing is simply a recipe. Follow the proper recipe and you’ll be fine.

I have moved to a new school and the English teachers there screamed me practically out of existence when I brought up teaching Chicago to my students. It seems to me that if we are challenging our students to think like historians, we should require them to write like them too.

I think you ask an interesting question; agreed, I too was surprised at first that MLA was taught in history classes instead of Chicago (I wrote my M.A. thesis with a Turabian book perpetually open on my lap). I think it is a couple things– connecting and synchronizing with the English department at my school is hugely important- and it really doesn’t seem developmentally appropriate to ask middle grade students to perfectly follow two different citation recipes- especially if they are using APA in science, too.

I really think that at this age it is much more important that students understand the why and when of using the recipe, rather than the specific rules of the recipe itself.

My 6th grade English teacher is confusing me. I have to write a research essay on year round schooling; I have been working on it for a week and just barely got through the intro because I just don’t get what she wants me to understand. This topic is also so boring … it would be easier if we had a fun topic. It’s my first year at Pinnacle which is for smart students and I don’t want to fail😓😓😔

This was a lot of help to me. Thank you so much for your hard work and inspiration.

Excellent article; thank you. Love how you are teaching them to write and cite!

i use this