Teaching Adolescent Readers in a Connected World

Connected Reading: Teaching Adolescent Readers in a Digital World

By Kristen Hawley Turner and Troy Hicks

(National Council of Teachers of English, 2015 – Learn more)

Connected Reading is not digital reading. Authors Kristen Hawley Turner (Fordham University) and Troy Hicks (Central Michigan University) make this point clear throughout their book Connected Reading as they work to separate the technology from the learning.

Instead, they are seeking to expand the notions of what reading instruction has become in a connected world:

We live in an era when readers navigate across devices, as well as across print and digital forms. Connected Reading embraces all kinds of reading, noting how textual features and contexts that include digital or print devices may shape a reading experience.” – Hawley Turner/Hicks, page 29

Engaging digital age readers

Hawley Turner and Hicks take a close look at how we are teaching, or not teaching, reading in a digital age, and how to engage readers in authentic ways, using a variety of texts, by tapping into the social aspects of today’s students.

The “connected” part of Connected Reading is the idea that technology is facilitating more areas of common ground among readers, either in the classroom or out in the real world, through shared annotations, community reading, crowd-sourced close reading strategies, and more.

What the Connected Reading concept highlights is the ways in which the barriers between writer and reader are being altered, and the book itself brings us into classrooms where these changes are afoot, often but not always facilitated with technology. (The authors make sure to show how this reading practice does not require a roomful of computers, as they document a teacher engaged in Connected Reading with almost no technology at all.)

Good and not-so-good assessment

Connected Reading itself is divided into sections around theory and practice, and it does not skirt the issue of the difficulty of assessing students who are engaged in Connected Reading practice. While the PARCC and Smarter Balanced standardized testing systems utilize technology for assessment of reading skills, the writers here express concerns that neither online assessment really captures the ways in which a Connected Reader truly engages with text.

They suggest formative assessment techniques that can be embedded in this kind of instruction, including having students:

- Maintain active digital reading journals

- Set goals around short-, mid-, long-form reading

- Share digital annotations of text for comprehension and reflection

- Utilize screenshots, included annotations, to capture student reading practice

- Create multimodal responses to reading of texts

There are plenty of helpful lesson plans and charts, annotated screenshots, and lots of solid resources about websites and apps and other technology in this book that can help bring the love and power of reading into the lives of young people. (See the Connected Reading wiki site for handouts, charts and additional resources.)

Insights informed by classroom realities

Since Hawley Turner and Hicks spent a fair amount of time working directly with classroom teachers, we also have their direct insights into the learning, as well as the results of an extensive survey that the two authors did with students. They ended up using that data to create “fictional reader profiles” as ways to bring student strategies around reading to light. (They also provide the entire survey in the appendix.)

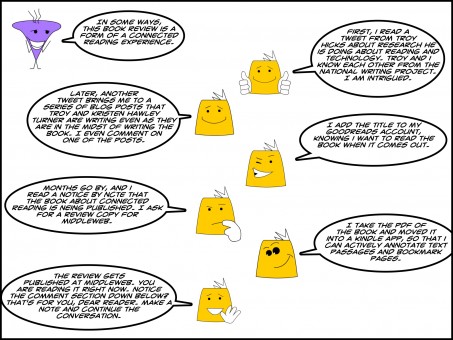

Interestingly, the two writers also share out their own Connected Reading practices, pulling back the curtain a bit on their personal reading habits. Their thinking out loud prompted me to consider my own experience with this book itself and helped me realize that the story of this review is yet another demonstration of Connected Reading.

by Kevin Hodgson

So what do we make of reading in the digital age?

First, I’d say that the authors’ findings reinforce the idea that the silent partnership between readers and writers is in the midst of a fundamental change. The barriers for engagement for readers of all ages – either through fan fiction sites, author blogs, annotation features, etc. – are lower than ever. At the same time, navigating those new avenues is a complex task and opens the door for teachers to meet a different kind of instructional need.

What is new, or at least very different, in the digital age is the agency afforded to all readers, especially teen readers … We encounter many kinds of texts on a daily basis, and we engage with those texts in a variety of ways. Most importantly, we are connected to other readers at every stage of the game. The context is broader and the opportunities more overwhelming.” – Hawley Turner/Hicks, page 54

Second, technology helps lower those barriers and opens the door to more social aspects of reading, and has the potential to engage students in reading texts in new ways. Collaborative reading practice can flourish, if students are provided with possibilities.

Third, the Connected Reading concept opens the door to teaching reading skills on screens – from the notion of hyperlinked text to embedded media to authenticity of sources.

And finally, the critical issue of access to technology becomes an overriding area of concern, for it in many ways determines which populations of students gain knowledge and experience of text in the modern age, and which populations are left lagging behind to learn on their own devices, so to speak.

The path forward

Connected Reading lays out the rationale, as well as a path forward, for expanding the definitions of reading, and those of us who love reading and who desire to instill a love of reading in our students – while balancing the act of documenting learning in this standardized testing era – would be wise to think about the lessons learned by Hawley Turner and Hicks in their research.

(A podcast interview with Hawley Turner and Hicks on the idea of Connected Reading theory is available at the NCTE site.)

Kevin Hodgson is a sixth grade teacher in Southampton, Massachusetts, and is the technology co-director with the Western Massachusetts Writing Project. Kevin blogs regularly at Kevin’s Meandering Mind and tweets more often than is healthy under his @dogtrax handle.

Skills building is different depending on the skills that are needed. There are some constants, however. A skill is truly mastered when the least possible assistance is needed for someone to achieve something. Think of training wheels that are eventually taken off bicycles; children are not deemed to be true cyclists unless the training wheels are off. Consider weight training. Nautilus machines, which guide your body parts through the entire cycle of motion are not sufficient for maximum gain; you have to be able to work with free weights.

So it is with reading, writing and math skills. I often think that students learn to master the highly regimented, automated and fully digitized tests we give them, because they become used to how the tests work, what the tests “want.” Using test-taking skills, they learn to eliminate unlikely answers and focus on the most likely desired responses. But is this “learning”? Do they truly understand what they are providing as the “answer”? I don’t teach anything like math, but I can still do long division, compute square roots and find the area of a circle, even if all I have is chalk and a board. My understanding of these basic concepts is complete, or very nearly complete. I seriously doubt this is true of many students. Instead, they have a fuzzy grasp of a great many concepts. I think it would be better if they had mastery of a smaller number. Asking students to “read” texts that whirl around animated pictures with sound playing in the background probably doesn’t lead to simple mastery of language itself. One of the problems is that they will never appreciate language by itself. As texting becomes an ever simpler, context-driven parlance, complex language will become unworkable and unknowable to a greater and greater number of people. Already, teachers have essentially given up assigning any work longer than 100 pages; students either cannot or will not read it.

You ask: “Using test-taking skills, they learn to eliminate unlikely answers and focus on the most likely desired responses. But is this “learning”?”

Nope.

Or least, not the kind of learning that we need young people to be taking on if we want them to be successful in the larger world — we need critical analysis, thoughtful writing, deep reflection and connections to the world. Few jobs are built around test taking (unless you get one of those hourly jobs at Pearson for grading standardized tests …)

I’m not sure I am as “doom and gloom” as your final comments about classrooms, but I do agree that the expectations of teachers to reach students in this “testing age” have put roadblocks in front of educators. We just need to hurdle higher.

Thanks for taking the time to comment.

Kevin