3 Strategies for Building Tween Resilience

Winston Churchill once said, “Success is not final, failure is not fatal: It is the courage to continue that counts.”

That’s really what resilience is about. Resilience is that “something” that helps us deal effectively with pressure: to bounce back from failure, and to address and positively overcome everyday challenges. Although there are many strategies for helping students build resilience, let’s look at three.

Communicating Effectively and Listening Actively

The first way we can support resilience is through our empathy with students. A key way we show empathy is by communicating effectively with our struggling learners, and that includes truly listening to them.

A teacher in one of my workshops shared with me that she always tried to take time for her students, especially when there were breaks between classes or activities. As you might imagine, she also had other responsibilities, so she typically scanned the room while talking to students, just to make sure everything else was running smoothly.

One day, as a student was asking her a question, the girl suddenly became quiet. When the teacher asked what was wrong, the student said, “You weren’t paying attention to me. You’re paying attention to everyone else.” The teacher immediately stopped, looked her in the eye, and said, “What do you want to say?” She began to listen actively as opposed to multitasking. That’s important to students.

We also need to make sure we are communicating clearly. There are four actions you can take to communicate more effectively:

- Fully answer the question being asked;

- Provide clear information;

- Be positive in your word use; and

- Finish with a question or a next step the person should take.

By following these principles in my classroom, my students understood me better, and it improved our relationship.

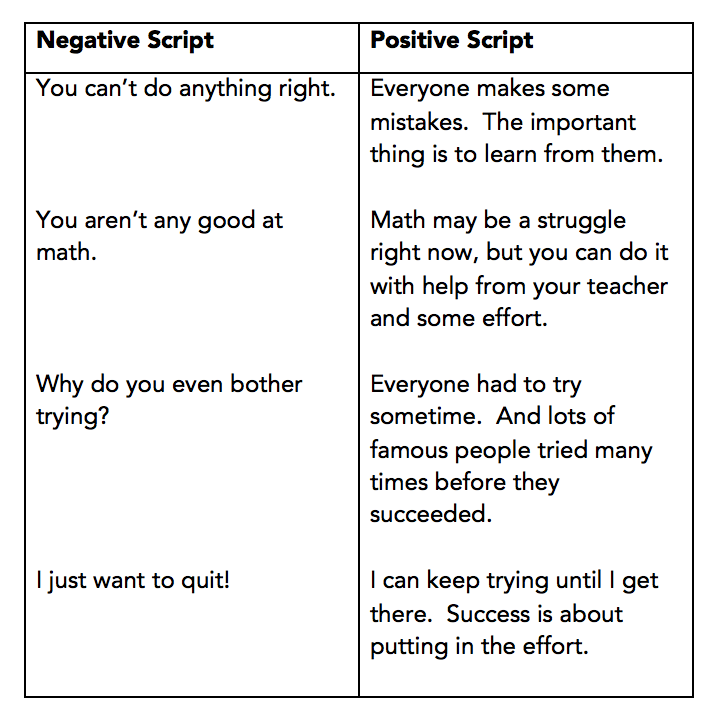

Changing “Negative Scripts”

Next, Students who are not resilient typically have a negative script running in their heads at all times. In their minds, they hear comments like, “You’re no good.” or “You shouldn’t have tried.” It’s important for us, as teachers, to address this with our struggling students, and help them reframe the negatives as positives.

Helping Children Recognize that Mistakes Are Experiences from Which to Learn

Finally, students who are not resilient often give up because they see even the slightest mistake as a permanent failure and a sign that they should stop trying.

Let’s look at an example of how to teach struggling students that making mistakes is a normal part of the learning process.

In their book, Raising Resilient Children, Robert Brooks and Sam Goldstein share:

One elementary school teacher told her class on the first day of school that throughout the year they would celebrate mistakes. She humorously explained that if her students did not make mistakes, she might lose her job, since it would mean that they already knew everything she had to teach them. She placed a glass jar on her desk with a box of stones and told them, “whenever you or I make a mistake, someone will come up and drop a stone into the jar. As soon as the jar is filled, I will bring in the popcorn for celebration.” Apparently the jar was small enough and the stones large enough that the party always took place within the first week. Students who typically would not raise their hands for fear of making a mistake now volunteered to answer; after all, if their answer was incorrect, they would be helping the class move one step closer to celebration.

By celebrating mistakes, students learn to embrace failure as a learning process, not as a stop sign for learning.

We can teach resilience to struggling kids

Resilience is the ability to effectively handle pressure and to overcome failure. It is a characteristic that many of our struggling students do not demonstrate in the classroom; yet it is one that we can teach. We do this by being empathetic, communicating effectively, and listening actively; by changing “negative scripts”; and by helping young adolescents recognize that mistakes are experiences from which to learn. These strategies can help us help our students learn to overcome failure, develop grit, and truly become resilient.

Barbara Blackburn is a best-selling author of 14 books, including Rigor is NOT a Four-Letter Word. A nationally recognized expert in the areas of rigor and motivation, she collaborates with schools and districts for professional development. Barbara can be reached through her website or her blog. She’s on Twitter @BarbBlackburn. See her other MiddleWeb posts here. Her latest book, Rigor in Your Classroom: A Toolkit for Teachers, was published in May 2014.

The post discussing active listening and changing negative scripts hit home with me. I immediately included the concept in a workshop that I am preparing for a group of parents of at risk students in a community where the school system has deteriorated over the years. Thank you MS. Blackburn and MiddleWeb. Glyndora