Help Student Writers Find the Best Evidence

No matter what grade or subject you teach, sooner or later you find yourself trying to help students write more clearly and convincingly. In one of my most-read posts for MiddleWeb, written in the early days of the Common Core implementation, I said:

One of the things students struggle with the most — and it’s relevant to every grade and subject — is distinguishing between argument and evidence. This problem manifests itself in both reading and writing…

In reading, students often cannot pick topic sentences or thesis arguments out of a lineup; and when writing, they tend to construct paragraphs and essays that lack arguments.

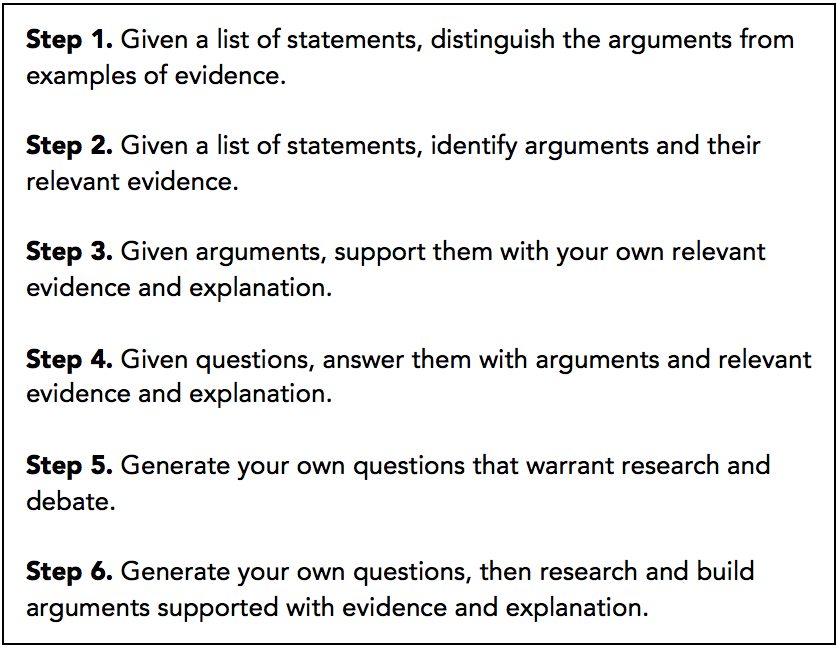

I went on to describe roughly six steps we can use to move students from “What’s the difference between arguments and evidence?” to “How can I write an effective research paper?” That’s such an important journey, and I want to share more thoughts about it, now that we’ve spent some years in “Common Core” classrooms. But first, here’s a quick refresher about those six steps for students:

Moving students through the steps

Lately, I’ve been working with teachers on how to help students write more effective paragraphs and essays. We have found that students can quickly master Step 1—applying the three rules for determining if a statement is an argument or not (it includes debatable/arguable words; it includes cause/effect language, or it raises “How” or “Why” questions). But they need more scaffolding to move from Step 2 to Step 3.

We are starting to think there may be a “Step 2.5.”

Step 3 gives students an argument and asks them to support it with relevant evidence and explanation. Breaking this down, it means they need to know what “relevant” means, how to select that evidence, and how and why to explain. It becomes more challenging to select relevant evidence when it appears not as a few isolated sentences but immersed somewhere in a complete text. You have to know what to look for and what to rule out.

Step 2.5 – Zeroing in on good evidence

Students have a tendency to look simply for words or phrases that seem related, and often their quest for evidence is too superficial, which causes them to select evidence that is not helpful.

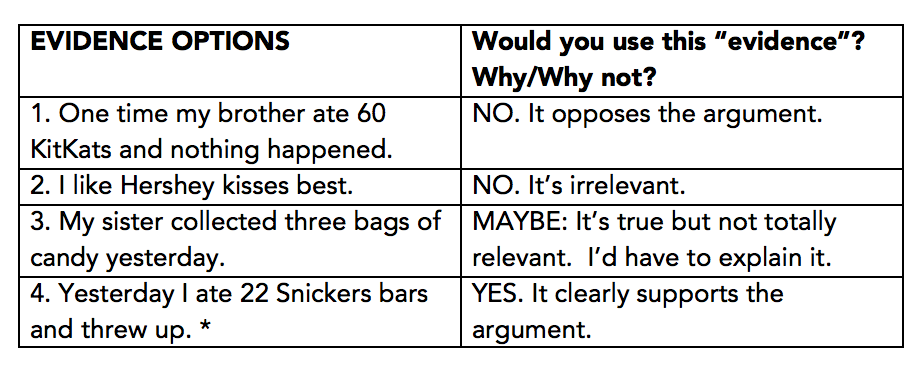

As part of the new Step 2.5, therefore, we’re teaching students what to rule out – the ineffective evidence. “Ineffective” evidence manifests one of three problems: 1) it opposes the argument, 2) it’s irrelevant, or 3) it’s true but not as relevant.

Here’s a tool we’re using to teach this point (download a Word doc):

Directions: Put a star next to the evidence from the choices below that BEST supports the argument. For each choice, tell why you would or would not use it. THEN write a logical sentence that would follow from your choice, explaining how the evidence supports the argument.

ARGUMENT: Eating too much candy causes stomach aches.

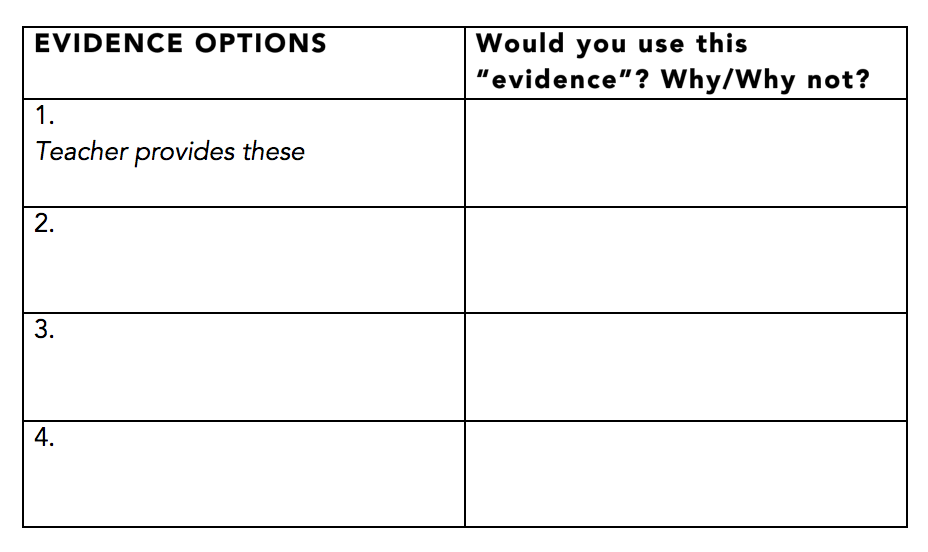

Here’s a template for practice (it’s part of the Word doc download):

ARGUMENT: [Teacher provides this.] ____________________________________

[In early practice, at least one evidence option should oppose, one should be irrelevant, and one should be true but not totally relevant. In later practice, you can mix/double up the options so that students won’t simply use a process of elimination.]

Good enough evidence

For more thoughts on how to teach “Step 2.5” see Part Two of this article, “Tools to Help Writers Explain Good Evidence”.

______________

Please provide a list of the statements, arguments, and evidence that you used.

Please see Part 2 here at MiddleWeb for an extended example of this “Best Evidence” strategy.

Hi, Tiffany–In addition to the other post MiddleWeb referred you to, I also have more explanations of the Argument vs. Evidence Steps 1-6 on my Website, The Literacy Cookbook. See under “Writing,” there’s a category called “Argument vs. Evidence,” here: https://www.literacycookbook.com/page.php?id=159 Also, please feel free to email me directly if you have additional questions. Thanks, ST

This was extremely helpful. I am an art teacher and my students are writing an argumentative essay.