How Feedback Can Be More Kid-Friendly

Most middle level teachers will tell you that they struggle with the paper load, especially as numbers increase in their classrooms. We are always looking for ways to streamline the process, make it more efficient and more timely in terms of getting work back to students.

However, our efforts in that direction sometimes have a down side: lost opportunities to “speak” to our students.

Middle school Language Arts teachers and content area teachers alike know the value of well constructed rubrics. In fact, rubrics have become the #1 assessment tool over the last decade.

Rubrics provide students with a clear understanding of expectations and are concrete representations that guide students through an assignment or project process. They clarify qualities a work should have and are a valuable learning tool in helping students understand the next steps necessary to become even more proficient in the work at hand. Once created, a rubric can make assessing large numbers of students more efficient.

The downside of rubrics

But here’s the problem. Overreliance on rubrics has come to mean, in many cases, that teachers are forgoing making comments and corrections. Many simply add up the rubric score and consider their job done. It’s not enough.

A measurement system in which the jargon includes words like “gradations,” “continuity,” “reliability,” and “validity” omits an essential element that is central to effective middle level teaching: personal communication.

Middle school students need to know they matter and that their efforts matter. Don’t we all, really? So while rubrics remain an important tool in all classrooms, we need a more whole-student approach to assessment.

Ideas to augment your feedback process

What are some of the ways that teachers, whatever our content area, can attend to that most basic need of our adolescent charges: one-on-one communication? Here are 11 ideas of mine:

► Write a “Dear Student” mini-letter on the rubric sheet before you return it. Not strengths and weaknesses; include words of encouragement. Students will love it.

► Be a selective assessor. If teachers feel they can’t possibly correct all errors in student work, they should select areas of focus for each new assignment, giving examples so that students are aware of those areas of importance before their work begins. Corrections would center on those particular focus areas (and students would know this). It’s important to remember that a piece of work devoid of any corrections suggests to the typical adolescent that all is well.

► Write notes of praise or concern to students who need a little extra TLC, not just about work but also about behaviors that the teacher perceives as exemplary, or a change from their norm, or bordering on problematic.

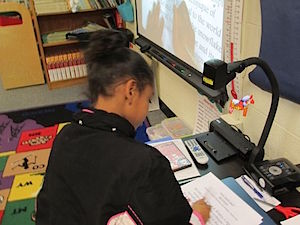

► Break the cycle of the routine “Hand In/Hand Back.” Take time to celebrate student work with readings or viewings on the document camera. (Check out these ideas at Pinterest.)

► Use student work as models, certainly as exemplars, but often students are cooperative about having their work shown for class editing or adding improvements if the teacher handles it in the right spirit.

► Make your students QUOTABLE! Excerpt a memorable line or a beautifully written thought or profound insight on the board and make it the Quote of the Week.

► When assigning projects, be definite about scale and size when it comes to posters or student-made models. This way it is easier to continually display their work in the classroom rather than have cumbersome projects that need to be removed immediately due to space issues.

► Create “books” – anthologies that compile student pages on a particular subject. Binders with glossy inserts make the job so easy, and students love to see their work “published.”

► Post student work on the class website, the ultimate act of feedback. Display student work in the library and on tables during Open House.

Extra work that’s worth the investment

There is no question that all of this requires extra work on the part of teachers. But if our goal is to go beyond the lip service of “reaching our students,” we have to find many ways to react to their work and to them as individuals.

The impact of constructive feedback is so powerful in promoting achievement. We all know that. An equally important dividend comes from the constant communication with students – it leads to trust which must be at the foundation of all that transpires in the middle school classroom.

__________