Students Need Time to Define STEM Problems

Anne Jolly began her career as a lab scientist, caught the science teaching bug and became an award-winning middle grades science teacher. Today she works on an NSF-supported team, developing standards-based STEM curricula for grades 6-8. Anne’s blog appears weekly at MiddleWeb, and one important focus is to engage readers in chats around STEM subjects. See all of Anne’s posts here.

Not long ago I sat listening to a speaker from the corporate world explaining to a group of educators what he needed his employees to be able to do. He skipped right over basic literacy and math (I guess he figured those went without saying) and went directly to teamwork and problem solving.

As he began talking about the kinds of skills that workers need to resolve problems common to his particular business, he suddenly stopped for a moment, gave a frustrated shake of his head, and remarked: “Heck! I just wish they could recognize a problem!” (He didn’t say “Heck.”)

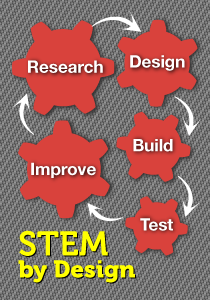

If we can get the STEM learning process embedded into our classrooms and schools, then this businessman is in for a happy surprise, because STEM lessons start with recognizing real-life problems. In fact, the first thing students generally do in a STEM activity is identify and define a real problem or a human need. This step is so important and so often given short shrift that I’d like to encourage you to join me and spend some time tossing around the “define the problem” stage of the engineering design process.

Let me confess up front that as I design STEM lessons, I’m aware that I’m often NOT giving students the time they need for the “define the problem” stage. Advocates of the engineering design process agree this should be a major focus of a good STEM unit. Albert Einstein famously said that if he had one hour to save the world, he would spend fifty-five minutes defining the problem and only five minutes finding the solution. By that standard, I’m certainly not building in all the time needed for students to improve their understanding of the dilemma: to analyze it and kick around some ideas together in an attempt to define it as clearly as possible. So how can I (and any of us) do a better curriculum design in this regard?

What I do now

In the real world, a person might have a blood clot break loose and go to a lung, causing lung injury (and even death). To introduce students to that problem, I might set up the scenario by showing a PowerPoint slide or video clip of an ambulance rushing a patient to the hospital, sirens screaming, along with a voice-over describing the patient’s symptoms. I might fast forward to a video of a doctor explaining the problem to the recovering patient (the patient always recovers in my classrooms). A blood clot had formed and gotten into the bloodstream, where it lodged in one of his lungs, causing pain and problems with breathing.

Now the students can recognize a real human need. But recognizing a need is not the same thing as defining a problem. Ideally the students would have time to research blood clotting and analyze the related issues, do some brainstorming, and define a problem for which they think they can design a solution. Instead, here’s what happens in this lesson: The doctor in the PowerPoint video guides them toward defining the problem by suggesting the need to design a method of preventing a blood clot from reaching the lungs (“catching” it).

That’s where I know I shortchanged them. I should have let them define the problem for themselves instead of fast-forwarding them toward a predefined solution.

But here’s the rub…

Finally, the STEM lesson had to correlate with the objectives that math and science teachers were teaching that quarter. How could I have truly let the students define the problem without leading them in a particular direction? Thoughts?

Some things we CAN do right now

Even with the time and logistics constraints on letting students puzzle over the problems, I’ve learned that these ideas can help to make problem-design a more valuable stage of the process:

- Make the need engaging. Start with an attention-grabbing scenario.

- Allow students to work in teams. (Read this earlier post and/or download this draft manual I’m putting together on student teaming.)

- See that students have as much information as possible about the need.

- Allow students some freedom to offer multiple perspectives, even when leading them toward a particular definition of the problem.

Examples of defining a problem

Some middle school teachers in the Mobile County (AL) school system have designed STEM lessons to share throughout the system; and they’ve correlated these with their math or science objectives. You might like to take a look at a few examples of the needs and problems these lessons address, and how they have defined the problem.

Need: Reduce our dependence on fossil fuels.

Define the problem: Design a system that increases the rate of photosynthesis in plants, and thereby the amount of glucose produced. (This teacher led her students to realize that glucose made by plants could be used to produce biofuel.)

Need: Address the needs of physically challenged people who require help reaching and moving objects.

Define the problem: Design an assistive device that can move objects in a specific weight range from the floor to a table.

Need: Prevent the spread of bacteria in packaged foods.

Define the problem: Design food packaging that will keep packaged foods at a temperature that prevents bacteria from growing.

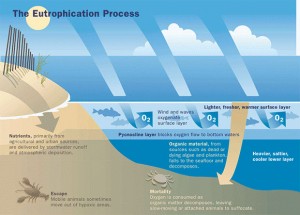

Define the problem: Design a research vessel that can collect and classify species of algae in the Gulf of Mexico (where Mobile is a port city).

As you can see, these teachers defined the problem for the students in order to incorporate the required content and have the time and materials they needed.

So again I wonder…

Do you have ideas about how a team of students can recognize a need and then define the problem themselves? Sounds easy, but it’s not. I think this stage of lesson creation frustrates me more than any other.

On a more positive note, even if you don’t have time to pursue all the solutions, why not ask your students to work together and come up with some problems or needs they have noticed. Things like cat hair getting stuck on furniture, wasting water in the home, how to position a guitar to improve its sound, and so on. Then ask them to study that need in more detail, including its causes, and ask them to clearly define the problem they believe needs to be solved.

The thinking habits that students can acquire as they practice doing this can help reduce the frustrations of the employer at the beginning of my post. Heck, we might even put a smile on his face.

The dilemma you describe is do real, Anne, and even after 30 years in middle school science teaching and lesson development, I am unable to find the time for students to dig into the “need and define the problem”. Perhaps the NGSS focus on bringing engineering into our science curricula will help?

I am registered for all of the NGSS webinars that NSTA is doing. Are you one of the hundreds who have registered for those? I’m blown away by what some of the presenters are showing us happening in science classrooms where these standards are implemented. Clearly, the most important support component for doing this correctly is time. Instead of two days, kids get 5 or 6 days to identify and define a problem, brainstorm and test multiple solutions, construct models and revise, and muck around in the thinking that goes into real world problem solving.

That’s where I think you’re right about the NGSS helping – if a state or district adopts the NGSS standards and implements these with fidelity, the issue of time to engage in engineering solutions will have to be part of that. How long do you think it’ll take for the huge status quo system we have now to make that turn?