Rummaging Around LOC.gov for Text Sets

A MiddleWeb Blog

I can talk all I want about the Children’s March in Birmingham, Alabama, when schoolchildren from across that city and beyond walked out of their schools and marched in a Civil Rights protest. I can try to explain the context and connect that to the novel we are reading, The Watsons Go to Birmingham 1963 by Christopher Paul Curtis.

I can talk all I want about the Children’s March in Birmingham, Alabama, when schoolchildren from across that city and beyond walked out of their schools and marched in a Civil Rights protest. I can try to explain the context and connect that to the novel we are reading, The Watsons Go to Birmingham 1963 by Christopher Paul Curtis.

I can talk about it from the teaching perspective but nothing compares to the voice and story of someone like Professor Freeman Hrabowski, who was actually there, marching in the protest as a child. Or we can listen to Anne Pearl Avery talk about joining the student movement in the South. Or….

The Library of Congress’s digital archives provides me with those voices and those personal stories, along with other important archival documents of the role of young people in the Civil Rights movement, images from the South during the unrest, and newspapers and other primary source materials.

And I can gather them up all from the comfort of home.

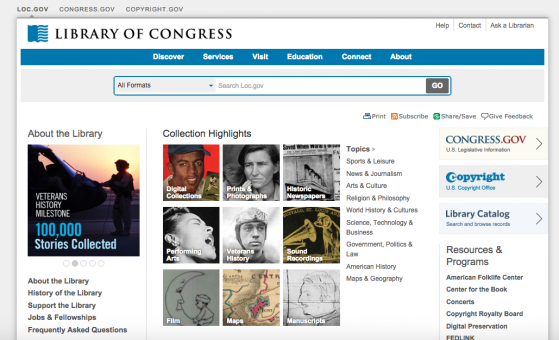

Truly, the Library of Congress digital archives are a wealth of information and a national treasure, with some reserved qualms on my part about the underlying search engine. I’ve been learning more and more about this site in recent months, as I co-facilitate a professional development course about using the Library of Congress to locate primary sources that will spark student inquiry.

We’re helping teachers not just to navigate within the Library of Congress archives, but also to develop “text sets” using an inquiry model that connects learning targets with primary source documents. These resources might range from maps to telegrams, from political cartoons to interview transcripts, from sound recordings to art and photography.

A national treasure filled with accessible resources

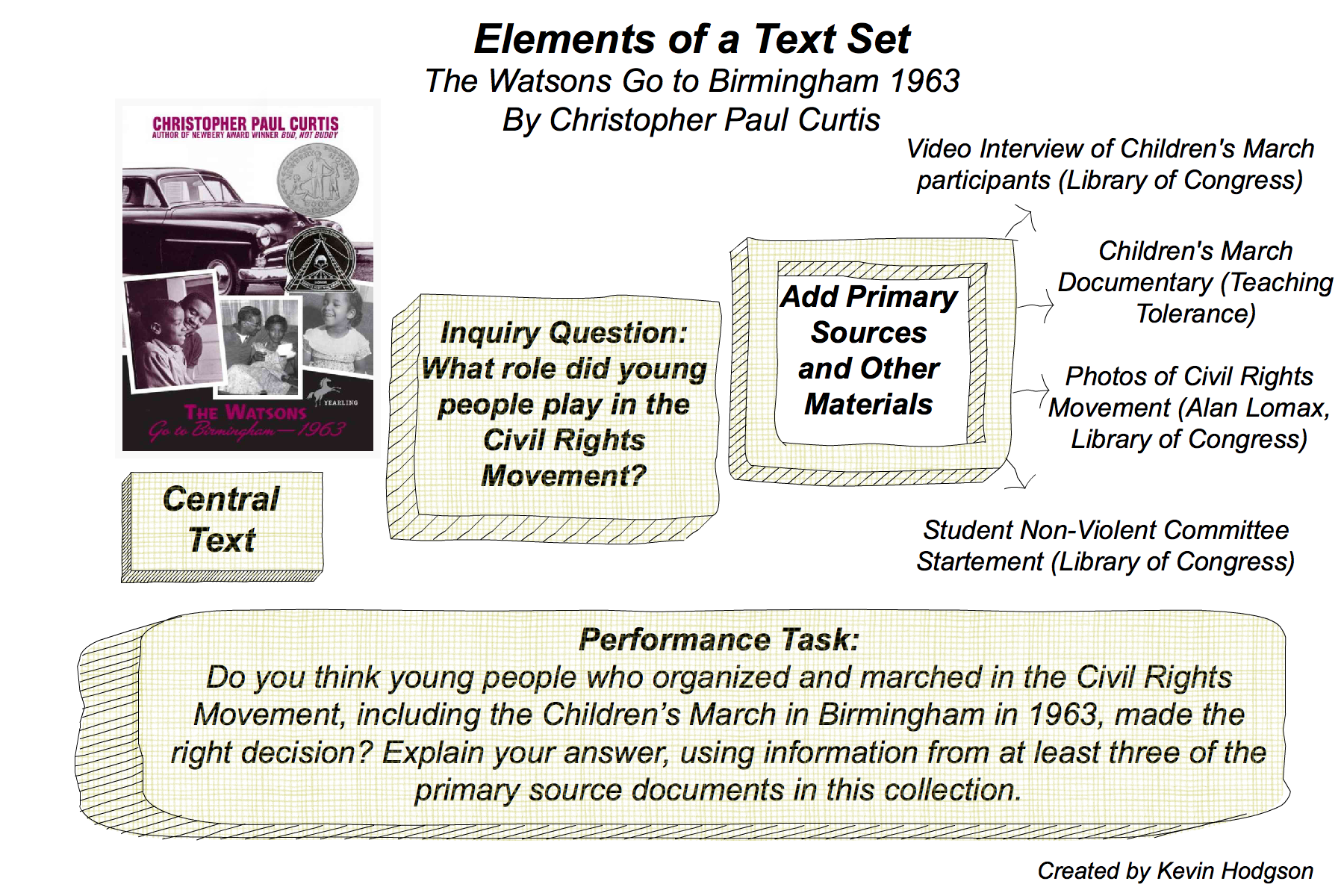

A text set, as we define it, is a series of texts that begin with some kind of anchor – either a novel, or a textbook passage, or a current events article, or some other kind of content reading that students will be doing.

From there, a teacher considers an Inquiry (or Essential) Question, and builds out a collection of five to seven primary sources for students to explore, with a performance task of some sort at the end. This could be a writing prompt, or some project that demonstrates understanding of how the anchor text and the primary sources work together on a theme.

So, for example, my text set for The Watsons Go to Birmingham was anchored to the novel, but then I began to collect primary sources of the Children’s March. Interestingly, the march itself is never mentioned in the novel. It does, however, play a prominent role in the movie version of the book.

A nonfiction text set about inventions

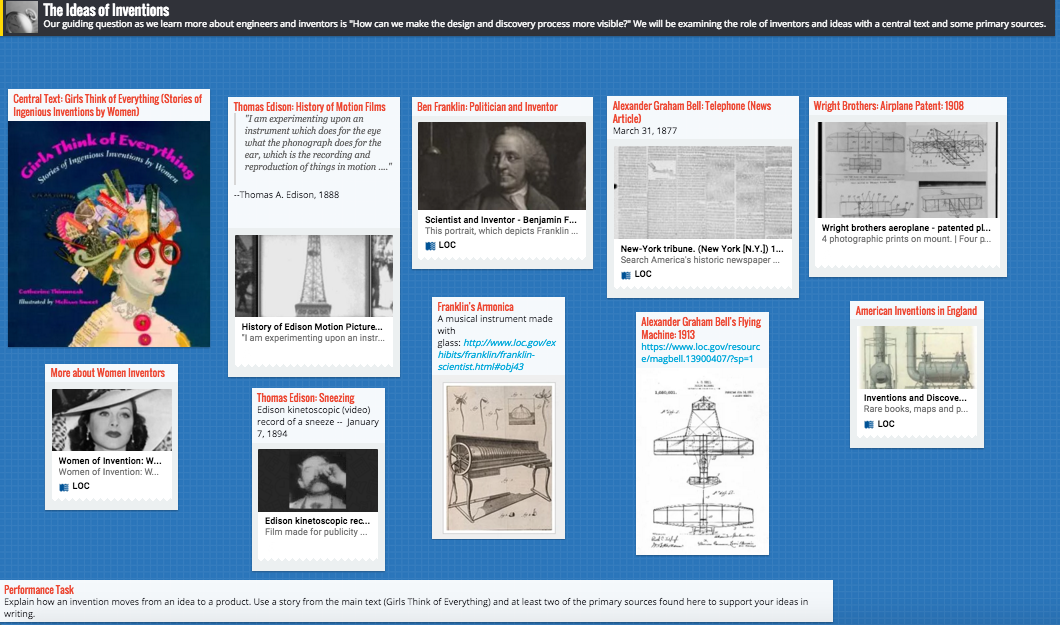

Another text set I am developing is about inventions, using a picture book (Girls Think of Everything: Stories of Ingenious Inventions by Women) as my anchor text, with supporting primary documents coming from the Ben Franklin and Thomas Edison archives, as well as from various patent design plans.

This particular text set aligns nicely with the new Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), which weave engineering design throughout the strands and throughout the grades.

The Library of Congress site is an incredible boon for gathering these kinds of resources. The organization has digitized thousands of historical documents, making them freely available to anyone with an Internet connection. On a global scale, the Library of Congress is also the force and support behind the World Digital Library, in which countries around the world are slowly making more primary documents available.

The LOC helps meet cross-curricular literacy goals

Certainly, the shifts in the Common Core have made it all the more important that teachers in all content areas pay particular attention to literacy. And some strands of the Common Core and other content-area standards are pushing for students to be taught more about primary sources and non-fiction texts in different genres.

Add to that the research component and the demands to reach across multiple texts, and the Library of Congress might have something to offer any middle grades classroom.

The Stanford Education Group’s “Reading Like a Historian” project (watch the video) is one of many rich resources now available to teachers that work well in conjunction with the Library of Congress site. At the Stanford site there are lesson plans, text sets, and research documentation of the gains made by students when using primary sources as reading materials. The Library of Congress also has many teacher resources that include primary sources, lesson ideas and more.

Some concerns about the search engine

My main reservation about the Library of Congress digital archives, as noted above, is that the search engine could be stronger and more intuitive, as could the overall virtual architecture of the site itself. It’s easy to get lost in there and not always easy to find exactly what you want. Search terms require exact spelling, and it will not intuit connected terms for you. Resources are sometimes buried in other resources.

It may be that we’ve become accustomed to more powerful search tools, and when we come across one that does not work like Google or Bing, we find fault. Guilty, but I’m still wishing the navigation at the Library of Congress was easier for non-researchers like myself. I imagine that day will come before too long, given some recent LOC leadership developments.

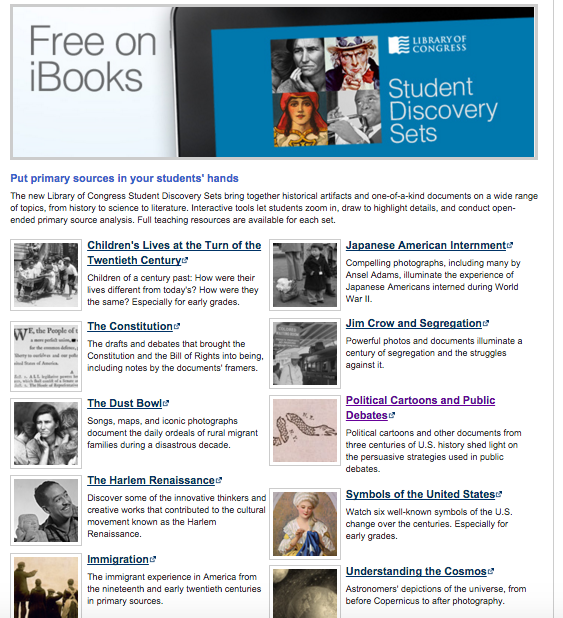

There are already indications that the Library of Congress is making progress in shifting to the demands of the modern age. For instance, it has established free ebook resources through the Apple iTunes Store for students with iPads and other Apple devices, with sets on diverse topics from Immigration to Political Cartoons to Cosmic Astronomy. When downloaded, the ebooks can be used by students to annotate text, highlight and more.

Teachers digging deep to enrich learning

The educators in our professional development sessions mentioned above are now in the midst of being researchers themselves, gathering up primary sources from the Library of Congress and beyond.

This work is not limited to English/Language Arts. We have a wide range of teachers in the class, from elementary to high school, from social studies to science. They will be building “text sets” and then teaching elements of those texts in their classrooms, sharing out what they are learning about bringing contextual history alive in their classrooms and in their various content areas.

And for myself, I am hoping that hearing the voices of people like Professor Freeman Hrabowski and Anne Pearl Avery, and watching video footage of the Children’s March, will connect my students not only the historical novel we are reading, but also to the world outside their windows, where movements like Black Lives Matter and others are galvanizing a youth movement in our current time.

History is about connecting to the present as much as it is understanding the past, and moving beyond textbooks into the sources themselves is one way to make that understanding more engaging, whether we’re teaching literature, social studies, or STEM subjects.

Really informative post! For curated sets of primary sources from LOC.gov and tips on finding and using the sources + teaching resources, check out the TPS-Barat Primary Source Nexus teaching resource blog.