Tools to Help Writers Explain Good Evidence

By Sarah Tantillo with Jamison Fort

By Sarah Tantillo with Jamison Fort

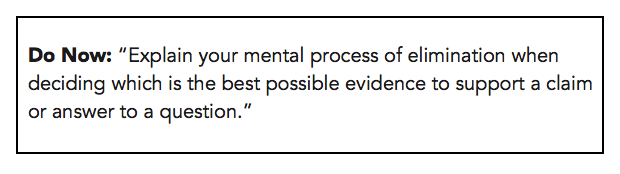

In Part I of this two-part series, I wrote about how we can help students rule out ineffective evidence when they are attempting to build arguments. The flip side of this work is to help them find the best evidence. In this post, I’d like to share a tool teachers can use to do just that.

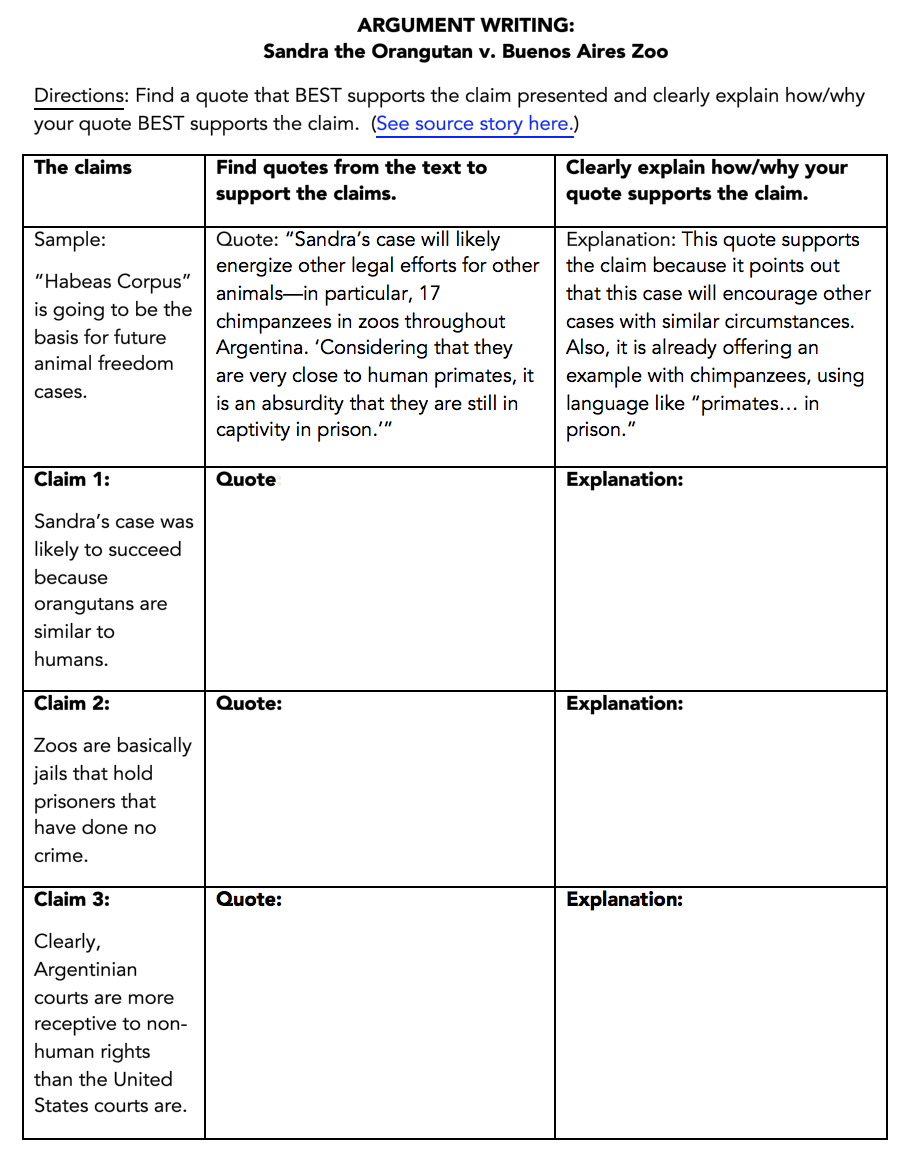

To give students more practice in finding relevant evidence on their own and explaining it, my friend Jamison Fort, who teaches 6th and 7th grade social studies, created the following organizer for students to analyze one text that has multiple claims. (We use “claim” and “argument” interchangeably.)

The rest of Jamison’s lesson

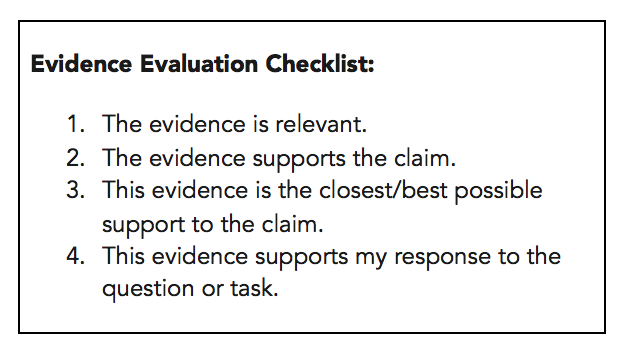

The day after this exercise, Jamison explained that the ultimate goal was to make sure that by the end of the next three days, every student would be able to evaluate evidence and choose the strongest possible evidence to support a claim. Then he launched the following lesson:

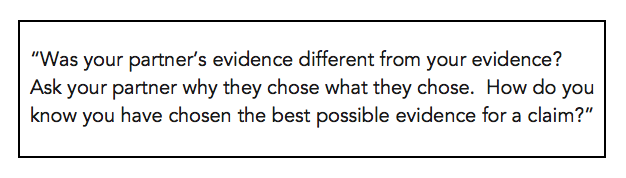

To expand their understanding of how to select effective evidence, Jamison turned to this activity: Students paired up and compared and contrasted the quotes they had chosen, then answered the following questions:

Students became highly animated in challenging his assertion, asking him to “explain his logic.”

He told them he didn’t need to explain his logic, adding, “I just know I’m right.”

Jamison could see his students’ frustration; they clearly knew he was wrong but couldn’t express how they knew. This was how he pushed them to use the tool they had just created. He wanted to show rather than tell them of its value.

After a moment of this student-teacher standoff, he diverted their attention back to the poster they had just created and asked them again, “Is there no one who can tell me why I am wrong?”

And then the connection was made, that “aha” moment. A girl who had taken up the role of class spokesperson said his answer was wrong because it didn’t meet all the necessary checkpoints: “It was related to the text, but not relevant to your claim.”

Once kids have the essentials, do some practice

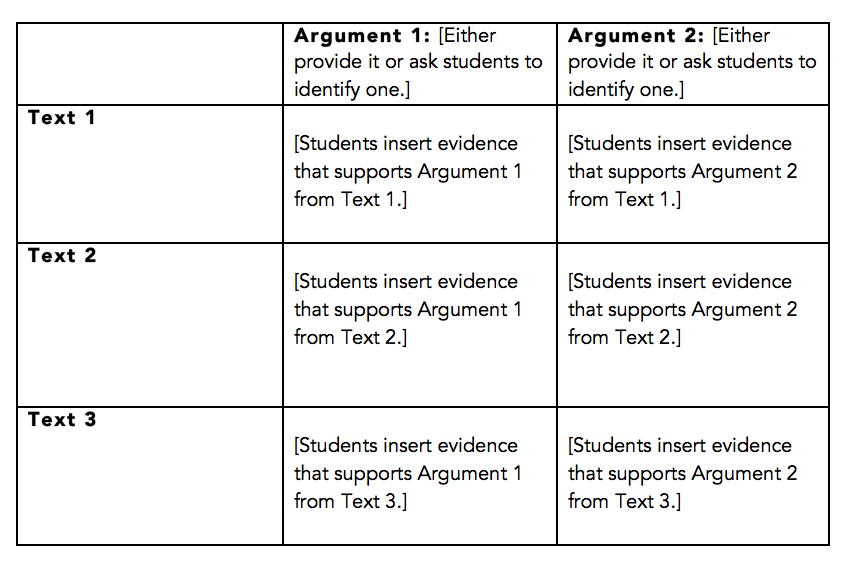

Once you’ve helped students grasp the essential characteristics of effective evidence, they can practice analyzing multiple texts, identifying arguments and key evidence. Here is a tool for that:

_______

Sarah Tantillo is the author of The Literacy Cookbook (Jossey-Bass, 2012) and Literacy and the Common Core: Recipes for Action (Jossey-Bass, 2014). For more information, check out her Website, The Literacy Cookbook, and her TLC Blog.

Jamison Fort has been a teacher for seven years, impacting the lives of students in Baltimore MD & Trenton and Plainfield NJ. Jamison challenges his students to constantly be critical thinkers and bring learning to life. In his two years at Maxson Middle School he’s created a competitive debate team and has had students present proposals to the mayor of Plainfield to create a community garden in the city. His collaboration with Sarah Tantillo has resulted in useful literacy tools and examples for other educators to use in their practice.