Involve Hesitant Writers in Co-creating Text

Just presenting students with model mentor text and asking them to emulate it is like showing kids a multi-layered wedding cake, handing them a pile of eggs and a bag of flour, and telling them to go for it.

How do we inspire writing excellence? With reading? Of course. Reading effective models? By all means. But we can’t stop there.

I admire wedding cakes as I do Olympic gymnasts and LeBron James. Viewing any of them can make me gasp with admiration. What the viewing cannot do is automatically make me a Michelin top chef, enable me sink a three-pointer, or stick a landing after a balance beam dismount. Not even with Bryant Gumbel doing a play-by-play on how to execute the moves.

In fact, I am so convinced I can’t do it, I wouldn’t even try.

The same goes for mentor text by stellar students

Turns out, there is one strategy that is worse than using text samples written by professionals, devoid of instruction, to un-motivate student writers. It’s using model writing from their peers.

“Sharing examples of stellar student work is a time-honored tradition for helping students understand how to improve, but new research suggests that, in some cases, it can turn off struggling students.” (Study: Showing Students Standout Work Can Backfire, Sarah Sparks)

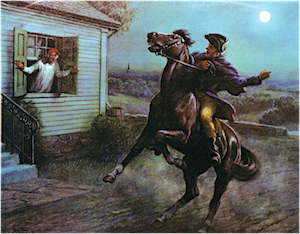

Believe me, I wanted to write like Longfellow, but it was so far out of reach, so dressed with pink roses and icing swirls, that instead of trying to copy his style, I copied a poem out of a book and turned it in. I got caught. What can I say? Desperate situations lead to bad choices.

While it was discouraging enough for me to try to emulate a dead poet, according to Sparks’ research it would have been worse if the exemplary writing had come from a classmate. The most popular cheerleader or basketball star probably would have authored it. I can feel myself curling up like a potato bug just thinking about it.

Co-creating mentor text “welcomes error”

As any middle school teacher will attest, there exists no population more inclined toward guarded self-consciousness than adolescents. It is not uncommon to see kids reduced to intellectual and physical paralysis. Worried that their peers may make fun of them for making mistakes, some refuse to even try.

Co-creating affords teachers the opportunity to break through this ice barrier by inviting EVERYONE to make mistakes. In classroom writing workshops, my partner Michael Salinger and I begin every writing session by sharing a sample from a professional writer. But we move on quickly to the process of co-creating our own Version 1. We make mistakes and encourage risk taking (after all, it’s just Version 1).

With input from students, we work through the messy procedure of assigning words to our ideas, bringing in ideas from all directions, tossing some out as being clichéd, prioritizing information. “See how we all make mistakes in Version 1? It’s a given.”

Then, and only then, do we ask kids to try it on their own or with a partner. Co-creating encourages an “I can try that” atmosphere in the classroom.

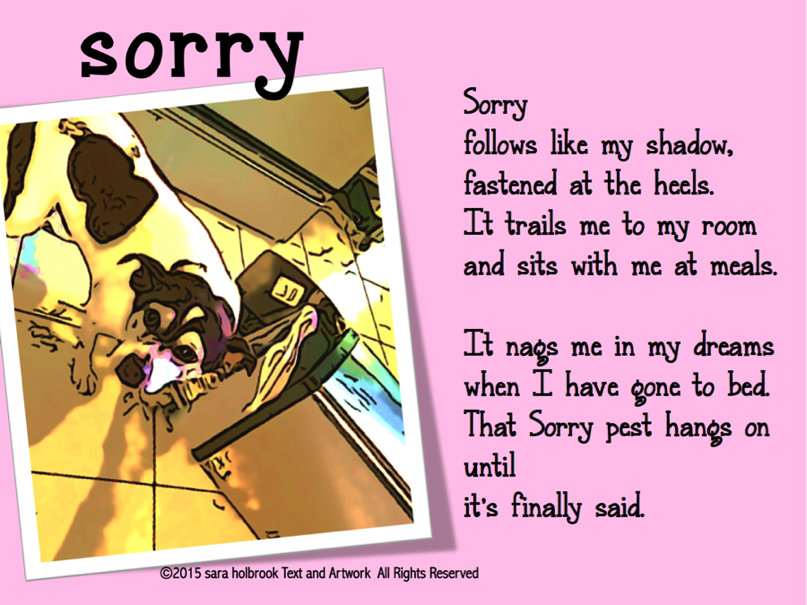

A personification poem in process

- We begin this particular lesson by sharing a poem that uses personification. This sorry poem is from a collection of my poems formatted for projection, By Definition: Poems of Feelings. I call it a Heads Up book, because as we project the poems, no one is bent over text, everyone is heads up, ready for discussion.

Analysis of the poem is brief: Can Sorry really sit next to me at meals? Does it trail along after me? This poetic device has a name: Personification.

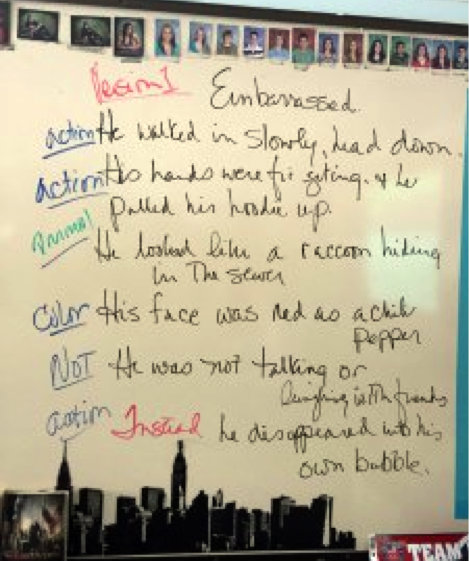

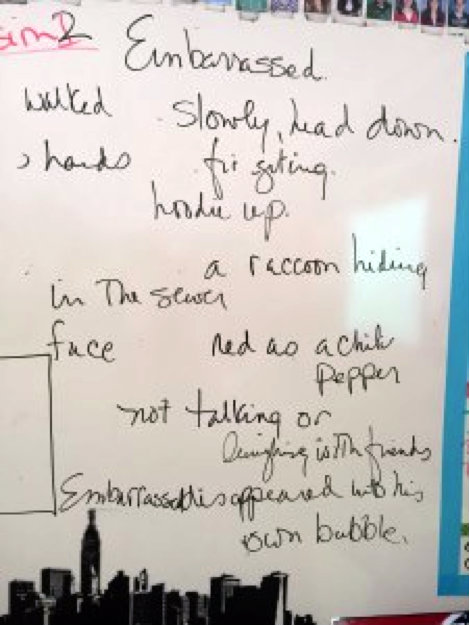

- Co-create a rough draft. We use the following framework of prompts for the first draft. We just made it up using actions, a simile, a color, a contrast and a final action. We go through these one at a time, building up the piece, taking several suggestions and talking through them as we compose. You may use this framework or make up your own.

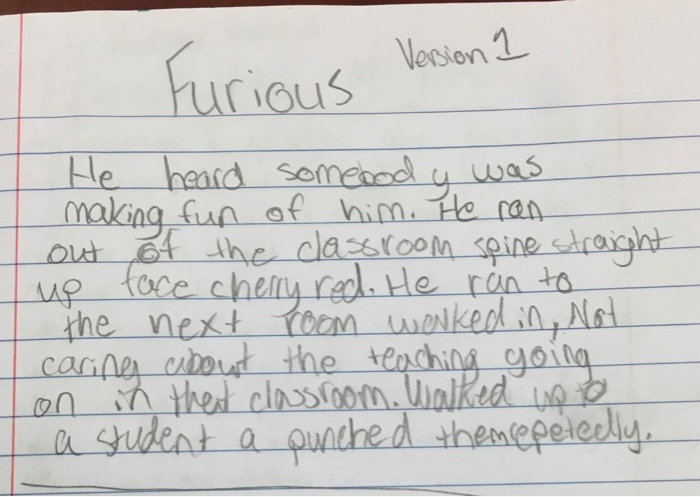

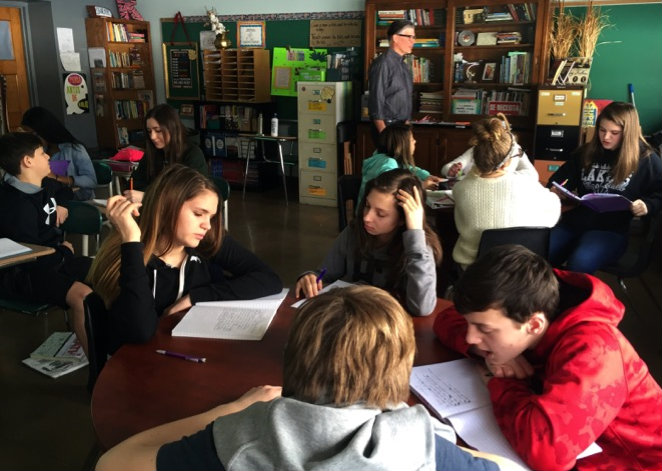

Below is a wordy, rambling Version 1 of a poem using personification, co-created with eighth grade students at Eastlake Middle School in Ohio in the classroom of a stellar teacher, Libbie Royko. Often first drafts have tense issues, unintended repetition, and point of view mix-ups. We acknowledge that we are making mistakes along the way, but don’t stop to negotiate adjustments. We get the words down first.

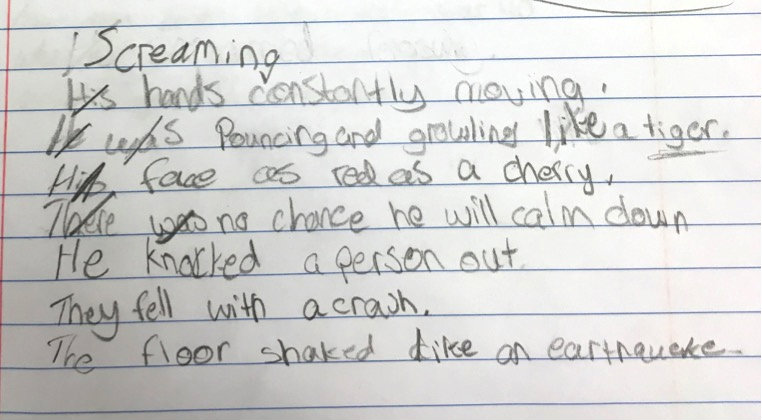

- Next we have students develop their own drafts. We prompt them one line at a time, walking them through the process we just did together, reminding writers to check our co-created version, remembering how we did that. No worries about getting it right the first time. Version 1!

- Later we work together to do a little trimming on our co-created Version 1. We work as a group negotiating line by line to see what words could be eliminated.

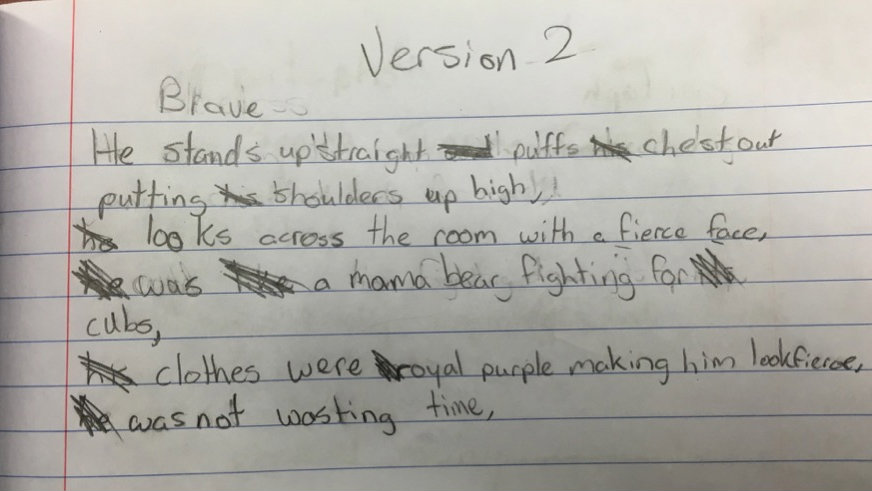

- Then we invite students to do some trimming of their own work. We challenge them to eliminate at least six words and celebrate when students offer that they have tossed four, eight, even twelve words. Below is Version 2 of the Furious poem as well. Note, the poet has also done some rearranging and added sound. Below that is another sample that personifies Brave, Version 2.

We aren’t there yet, but the poetic process is launched, using a simple framework. The students then continue to work, rearranging, adding, subtracting and making the poem their own.

Repeatedly we affirm that this is not the only way to write a poem, that there are roughly a gazillion paths to poetry, this being just one. In fact, it’s a path we just made up. We invite the students (and teachers) to make up their own.

Sampling

Sampling

Finally, students share their own Version 2s aloud, talking through the process as a writing community. Little steps, improving our communication skills, sampling each other’s concoctions. Saying the words aloud, seeing what feels right on the page and on the tongue.

This time we aren’t sampling one of those stilted cakes, monuments to perfection with fancy frosting swirls and tiers, but the best kind of cakes. The tasty ones with dents and crumbly parts. The ones we make on our own.

Sara Holbrook is the author of over a dozen poetry books for kids and teens as well as books for adults. An award winning performance poet, she has worked with middle grade student writers for over 20 years. With her partner Michael Salinger, she is a frequent presenter at local, state and international conferences in addition to consulting with schools all over the world, helping students clarify ideas and find their voices through writing. For more information about them visit www.outspokenlit.com. Check out their blog for more classroom ideas.

For a more detailed plan of this lesson (among others), including how to align it with standards and an assessment rubric, you may consult Sara and Michael’s most recent book: High Impact Writing Clinics, 20 projectable lessons for building literacy across content areas (Corwin, 2014).

Nice, very thoughtful and strategic, Sara. Another, very different way to approach hesitant writers is by drawing on students’ concerns about real-world issues in their school or community. My new book from Heinemann — “From Inquiry to Action” — is about guiding students to identify, research, and take action on issues in their world. –Steve Zemelman