Total War: Wrestling with a Scholarly Article

A MiddleWeb Blog

The books are often easier for them to dig into, with narratives that pull us through: Christine Stansell’s The Feminist Promise: 1792 to the Present or Joseph Ellis’ Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence.

Journal articles I use more sparingly, partly because most adults do not read them and mostly because they are difficult.

But once in a while I find the perfect source on ProQuest Research Library or JSTOR – such as Lance Janda’s article “Shutting the Gates of Mercy: The American Origins of Total War, 1860-1880,” from the Jan. 1995 Journal of Military History.

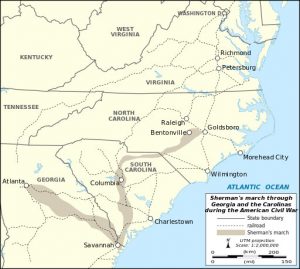

For our unit on total war, which starts with Sherman’s March to the Sea and continues through the atomic bomb and 9/11, Janda’s article both described the Northern generals’ shift in approach and explained the philosophy behind it.

Sprinkle definitions throughout

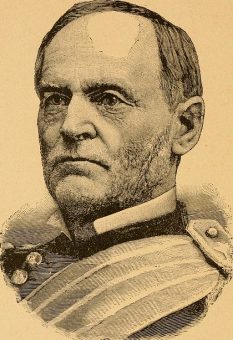

At times Janda used colorful language to drill down into the minds of Ulysses Grant and William Sherman, such as the following excerpt, for which I added the bracketed definitions:

If the blast furnace of war produced a Grant cleansed of restraint [without much self-control] it also kindled [lit] the righteous fury [justified anger] of William Tecumseh Sherman, whose name would become synonymous with destruction throughout the South. His famous March to the Sea and March Through the Carolinas have become infamous [famous in a negative way] through tales of wanton [deliberate and unprovoked] and complete destruction.”

Janda’s article also frames total war in three categories students can easily understand, and I bolded the key words to make the categories even clearer:

In his writings Sherman again noted the three tenets of his philosophy of total war. The first was military necessity, for he believed that destruction of civilian property and supplies shortened the war by depriving Southern armies of material support. Closely related was the notion of psychological warfare, depriving the Southern people of their spirit, and dousing their enthusiasm for war. Finally, there was the idea of collective responsibility, the belief that whatever happened, the South deserved it.”

When assigning such an article – usually only several pages of it – I tell students that they will not understand everything, or even most of the piece. They should underline and annotate what sounds interesting to them and not worry about the entire argument. My goals are familiarity and comfort, not complete comprehension.

What do I want them to get from the article?

Questions more than answers. The sense that many minds have fought through these issues and the verdict is still not certain.

One of my favorite question-generating approaches is the Question Formulation Technique outlined by The Right Question Institute, based on Dan Rothstein and Luz Santana’s Make Just One Change: Teach Students to Ask Their Own Questions.

When students brainstorm questions in groups, they follow protocols that include “Write down every question exactly as it is stated” and “Do not stop to discuss, judge, or answer the questions.”

Such rules ensure that every student’s voice is heard and that, ideally, no one feels judged.

For the total war article, the prompt I gave for small groups was: Brainstorm as many questions as you can think of about the article: general or specific, philosophical or factual. Use your annotations if you get stuck – what annoyed, frustrated, delighted you? These questions will also get your thoughts flowing for the total war debate in a couple of weeks.

The results, as they always do when I ask students to ask the questions, ranged wider than I could have gone on my own. Here are three classes’ favorite questions from their group discussions:

Section 1

- Why was Sherman so relentless?

- Did any soldiers refuse to carry out the cruel acts that Sherman ordered?

- Which of these three topics most influenced the North to use total war (military necessity, psychological warfare, collective responsibility)?

- Do you think that total war was necessary?

- Why didn’t the South use total war on the North?

Section 2

- Was total war a necessary evil, or was there an alternative solution?

- Why did Sherman follow through with his actions, even though he knew the consequences?

- What was the mindset of the soldiers during total war?

- Could total war lead to a dictatorship?

- What triggered Sherman’s change on total war, from 1862 to 1864?

Section 3

- If our only justification for total war is “they did it first,” then what makes us morally better than our opponent?

- Even if you’re not directly fighting, are you still engaged in the war?

- Why would you have to destroy whole entire cities and neighborhoods, not just military necessities?

- Why was honor more important than success?

Was the activity imperfect? Of course. I could not expect most eighth graders to be able to trace Janda’s argument or even to follow all of his sentences.

Mostly, though, I wanted them to grapple with ideas in a way that made them feel smart, part of an ongoing historical conversation. And we left class with more questions and less certainty than we had when we entered, buoyed by an author who helped us know where to begin.

Image credits:

Cover image source

Columbia, SC – George N. Barnard [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Sherman’s March map source

William T. Sherman source

Who, when and how are the students questions answered?

Suzanne, Thanks for this practical question. For the straightforward factual questions (“What triggered Sherman’s change on total war, from 1862 to 1864?”), I try to answer them when circling around to the different groups or by asking the students to go back into the article we read. For the factual questions I don’t know (“Did any soldiers refuse to carry out the cruel acts that Sherman ordered?”), I tell students that they can do research on this as part of the debate on total war that we’ll have in a couple of weeks. And, for the philosophical questions, (“If our only justification for total war is ‘they did it first,’ then what makes us morally better than our opponent?”), we try to at least begin to answer them in the debate.

Sarah – I’m quite pleased and impressed and flattered that you’re using my article in an eight grade class. Your lesson plan is amazing. You’re getting your students to do a lot of high level analytical thinking. We struggle to do that sometimes at the university level, and it’s great that you’re making your middle school students hone those skills at such a young age. (I wish my daughter had a teacher like you). I wrote that piece back in graduate school, so it’s nice to know it’s still being read. If I can ever be of help – talking shop with you or answering questions from the students – I hope you’ll let me know. Thanks for making my day!

Lance Janda

Lance, you’ve now made my day! How wonderful to hear from the author himself. Thank you so much for your kind comments and your offer for future connections.