Do We Really Know How to Teach Argument?

By Erik Palmer

By Erik Palmer

I bet you have noticed that some of our favorite writing prompts are losing favor. “What I Did Last Summer” and “My Funniest Moment” narratives are being pushed aside. We are being asked to focus on informative, expository, and argumentative writing.

Many teachers are resistant, but I think it will be good for students. We stress different genres in reading; we should teach different genres of writing. But how do we teach argumentative/persuasive writing and speaking? I do lots of workshops with teachers around the world, and it is obvious that most of us feel unprepared.

Here are some questions I ask teachers at workshops:

What is an argument?

That seems like a pretty easy question, but do an experiment. Ask the teachers at your school to write down a definition without using a dictionary or searching online. You won’t get the same answer twice. We all sort of know what an argument is, and it seems like a common term, but we don’t have an exact, agreed upon definition.

Because all of our students have heard the word before, too, we think they understand when we say, “Analyze the argument…” or “Write an argument supporting…” but they really don’t. Ask students to define argument. You’ll see what I mean.

What are the pieces needed to build an argument?

You could do the same experiment as above. Ask teachers to tell you exactly and specifically what they think students need to create a good argument. Again, you will never see the same answer twice. Claim, warrant, reason, plausible argument, stance, strong reasons, position, conclusion, facts, details, quotes, evidence, backing, premise, correct logic, logical progression of ideas, statement, thesis, and various other related terms. No agreement. Competing ways to say the same thing. Confusing to students and adults.

How do you teach students to build a good argument?

Before we ask students to write an essay, we have been clear about the pieces needed, and we have taught specific lessons on each of those pieces. We teach sentence structure and have practice activities with fragments and run-ons. We teach topic sentences, paragraphing, word choice, punctuation, capitalization, and so on.

But what lessons do we teach about the pieces of arguments? I have gotten some strange answers from teachers as I lead workshops on the topic:

Teacher A: “I tell students to come up with a good position and give three strong reasons for it.” OK, how do you teach them what a “good position” is? Why is one position “good” but another not? The teacher had no answer, no lesson about that. OK, how do you teach them what a “strong reason” is? Define strong reason versus weak reason and show me your “strong reason” lesson. Again, no answer. It’s unfair and unproductive to ask students to do something without teaching them how to do it.

Teacher B: “I don’t believe in telling students what an argument is. My class is about student self-discovery. I want them to find out for themselves.” Really? That seems like a convenient dodge. Do we do that with common denominators? “2/3 plus 2/5 equals 1 and 1/15. Figure it out. Good luck, kids.” When you consider that standards are asking even very young children to recognize and create arguments, this is especially poor. Just hope they get it without any direct teaching?

Teacher C: “I show them procon.org and Oxford debates.” Showing models of arguing is useful, but we don’t teach anything else by showing models only. Yes, reading good material supports writing, but if you told your administrator, “I teach writing by having kids look at good stories,” what would be the response? “Anything else? Specific lessons about using commas in a series, subject/verb agreement?” “Nope! Just look at good writing.” Tell me how that works for students.

The bottom line is that very few of us have a solid definition of argument, a great understanding of the pieces of argument, and specific argument-building lessons. That’s a problem in a time when teachers are being asked to have students do more argumentative writing and speaking.

I ask another question at workshops, too: Has your school or district provided resources and/or training about teaching argument? By far the most common answer is “No.” It is grossly unfair to ask teachers to teach something without giving them resources and training to do so.

It gets worse.

Arguments should be supported so we are tasked with teaching how to evaluate and use evidence. I ask teachers how they teach evidence and this is a typical response: “I tell students to add facts, evidence, etc.” Stop right there. Actually, facts are one type of evidence and I’m pretty sure “etc.” means “I don’t know anything else.” Do all of your students understand that there are types of evidence? How do you teach those?

Don’t think that because words are recognizable, they are understood. Argument, persuasion, evidence, and reasoning are common words (rhetoric less so), but that doesn’t mean students (or teachers) can master them without direct instruction. I wrote Good Thinking: Teaching Argument, Persuasion, and Reasoning to give teachers an understandable, practical way to teach students these important skills. There are some core principles in the book.

Core principles

► A common language is important. Shifting vocabulary from class to class, grade to grade is not OK. “Position with reasons and quotes” in English and “Conclusion with warrants and backing” in social studies, and “Opinion with evidence” in health is not optimal for students.

► Take nothing for granted. Define and teach “argument.” Explicitly explain the steps needed to build an argument. Teach five types of evidence and give students practice finding them. Teach persuasive techniques and give students practice with them. Teach grade appropriate rhetorical techniques and give students practice.

► Every discussion, every book, every news story, every math problem, every “Can we go outside?” is an opportunity to teach good thinking. You have activities that can be tweaked to make all of the needed teaching possible, workable, and even fun.

► Teaching students about argument, persuasion, and reasoning will benefit them for their entire lives. Knowing how to evaluate and create these will be important every day in their professional and social lives.

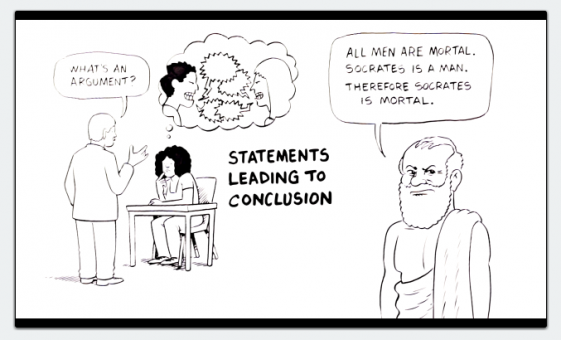

You can get a sense of my framework for teaching these concepts in this video:

As you noticed, I offer this definition of argument in the video:

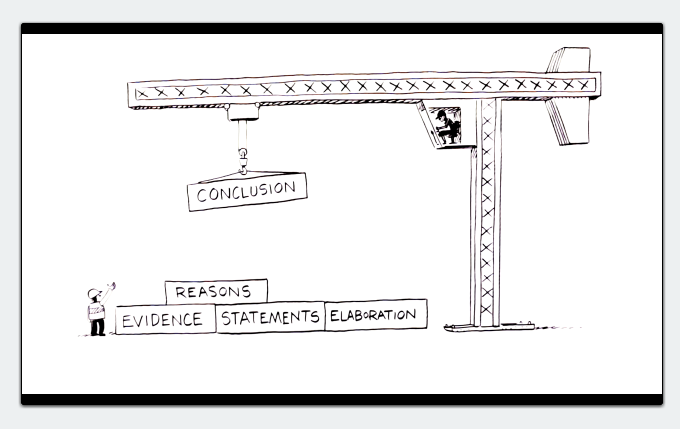

An argument is a series of statements leading to a conclusion.

This is an important definition that will ultimately make your teaching life much easier. If we get in the habit of using this definition, thinking improves. Some examples:

Example #1:

Student: I think we should ban large sugared soft drinks.

Teacher: That is an interesting argument. What is the reason you said that?

Error #1: That is not an argument. That is a conclusion. It is the end product of some line of thinking, the last piece of some argument.

Better:

Student: I think we should ban large sugared soft drinks.

Teacher: That is an interesting conclusion. What is the reason you said that?

Error #2: Imprecise language can lead to misunderstanding.

Student: I think we should ban large sugared soft drinks.

Teacher: That is an interesting conclusion. What is the reason you said that?

Student: Because you asked me to tell you what I thought about soft drinks.

Better:

Student: I think we should ban large sugared soft drinks.

Teacher: That is an interesting conclusion. What statements would lead us to that conclusion?

Example #2:

Student: I think we should ban large sugared soft drinks.

Teacher: That is an interesting conclusion. Give me two reasons to support that.

Student: Drinks have lots of corn syrup. Kids are fatter today.

Error #3: Why two? What if it takes more statements to lead to the conclusion?

Error #4: Let’s not use the word “support” yet. It has a better place, as you’ll see.

Error #5: The student gave two statements, but how do they add up to “Ban soft drinks”? Drinks have corn syrup. So? Why does that mean they should be banned? The student hasn’t built an argument yet, but has given random statements.

Better:

Student: I think we should ban large sugared soft drinks.

Teacher: That is an interesting conclusion. What statements led you to that conclusion?

Student: Drinks have lots of corn syrup. Corn syrup is the worst and leads to obesity. Obesity is a big problem now. So we should ban those drinks.

Teacher: I see. Well that does add up, for sure. Those statements would lead me to your conclusion and make me think your conclusion is correct.

Now we can use the word “support.”

Teacher: Now we have an argument. But it seems some of your statements need support. “Drinks have lots of corn syrup?” Do you have any evidence for that? “Corn syrup leads to obesity?” Do you have evidence for that? “Obesity is a big problem?” Evidence?

With consistent, precise language, the students know what is required, and quickly get the idea of how to build an argument. Now we can teach the types of evidence: Add a number about how much corn syrup is in a drink; add a quote from a doctor who works with obese children; add an example of a child who drinks lots of sugary drinks and got fat; add a fact about how the body metabolizes corn syrup; and add an analogy about how banning sugared drinks would be like banning asbestos.

That wasn’t so hard, was it?

We change our language to be consistent and specific, and we teach a couple of mini-lessons just as we do with every other subject. We are well on the way to having arguments supported with evidence. (Persuasion, rhetoric, and reasoning can be easily taught, too, but they are the topic of another post.)

A little upfront investment in teaching these skills will make so many things better in your class and beyond—analytical reading, discussions, writing, speaking, and more. You will notice the improvement as your students demonstrate good thinking.

I like your idea of common vocabulary across the disciplines when asking for the same thing. School-wide changes like this can have a lot of impact. Didn’t the teachers you reference here have to write argument papers in college and take speech classes? Teaching thinking, persuasion, argument should also be covered in methods classes in teacher training.

I dislike the idea of common vocabulary. What will happen when students go off to college and every professor uses a different term. There is no way that you are going to get the whole world to use common vocabulary. Students have to be exposed to all the terms, and their nuances, so that they know what is being asked of them if it is asked a little differently sometimes. The purpose of teaching argument is to get students to reason logically.

When they go off to college, because they have all been exposed to a simple, common vocabulary as young children (enabling them to understand argument well), someone will be able to say, “I know you all understand ______ so let me introduce another way of looking at…” You don’t start with obfuscation. We have a common vocabulary for most everything: e.g., you don’t find one teacher saying, “Proper usage of large letters” and another saying, “Cases appropriately applied.” We all agree to teach “capitalization.” To think that a child will not be confused by warrant, claim, reason, statement, conclusion, backing, evidence, support, and more, is a mistake. Save college-level thinking for college.

Thank you. That was as clear an article on the topic as I’ve seen written. Distinguishing between evidence and support was especially helpful.

I’ve always taught students that the difference between persuasive writing and argumentative writing is that persuasive writing generally ends with a ‘call to action’ – the need to do something with some urgency in order to make a change. OTOH, argumentative writing builds to a well-grounded, logical conclusion for the reader to consider and in the hopes that they might be swayed. The lack of immediacy or urgency and the lack of a direct call to action is the difference between the two.

Is my assessment and explanation of the difference between the two accurate? It’s especially of concern insofar as this is the change on the PARCC test (I’m in NJ) ~ from ‘persuasive’ to ‘argumentative’ writing.

Thank you for your feedback.

Yes, I think that is one way to look at it. Certainly I hope you will think my argument is compelling and be wowed by my logic, but I haven’t added anything to SELL the argument. Telling us that we MUST ACT NOW! is one way to sell, but urgency is not the only way to sell.

I really enjoy how you explain it, but i have a huge doubt about it. I have to plan an entire class for teaching how to do an argument… How can I start? How can i create a cool warm up about this topic for teenagers?