Rick Wormeli: The Right Way to Do Redos

Adapted from Fair Isn’t Always Equal: Assessing and Grading in the Differentiated Classroom by Rick Wormeli. Copyright © 2006, Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

In a successfully differentiated class, we often allow students to redo work and assessments for full credit. There are a number of stipulations and protocols that make it less demanding on teachers and more helpful to students, however. Let’s take a look.

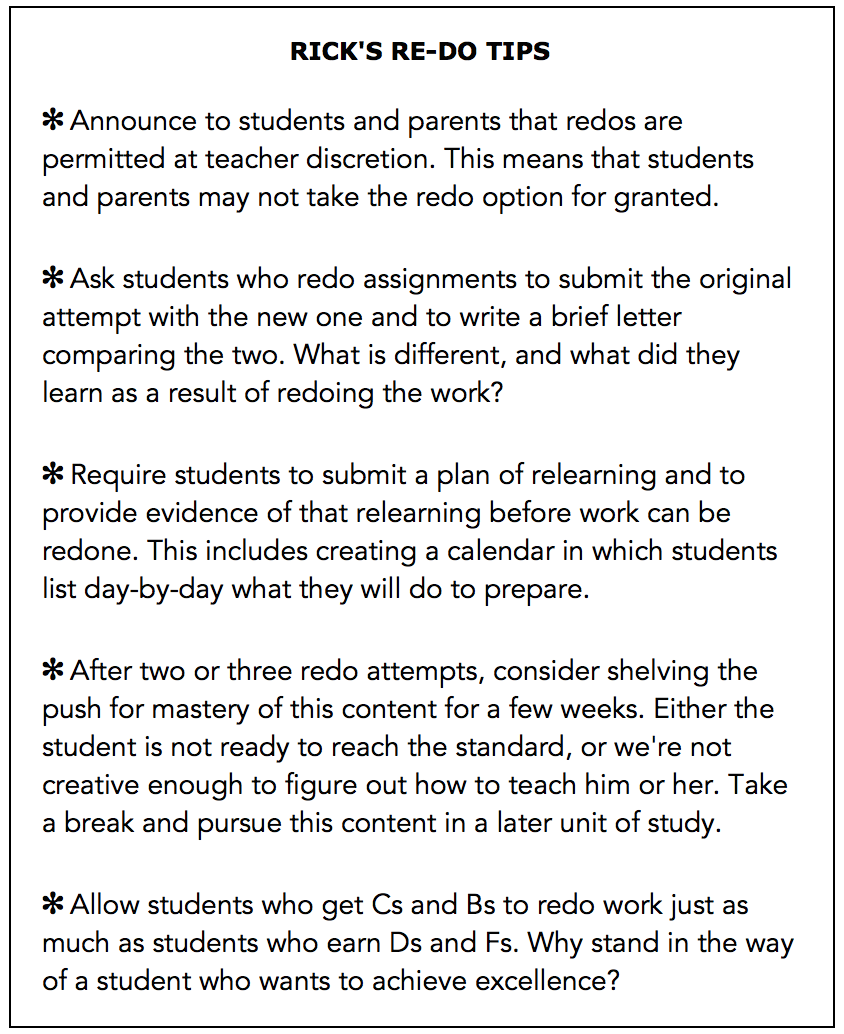

All Redone Work Is Done at Teacher Discretion

Redoing work is not to be taken for granted. In my classes, I ask parents to sign a form that outlines this and other protocols for redoing work at the beginning of the school year. This serves as due process, and I can reference it when a parent complains that I did not allow his or her child to redo an assignment.

If I get a hint that the student has “blown off” a four-week project until the last three days, or boasted to classmates that he or she will just take the test the first time as an advance preview and then really study for it next week because, “Mr. Wormeli always let’s me redo tests,” I will often rescind the offer and discuss the situation with the student.

If it’s a character issue, such as integrity, self-discipline, maturity, and honesty, the greater gift may be to deny the redo option. We have to weigh that choice every time we consider allowing students to redo work.

Also, if a particular student is asking to redo work more than twice a grading period, there may be another problem that needs to be addressed. We may need to modify our instruction, coach the student on time-management skills, confer with the parents, look at the student’s schedule outside of school, or get some guidance from a school counselor because of a difficult emotional issue the student is experiencing.

The rule of thumb, then, is to consider the extent to which students abuse the policy by becoming chronic redoers. If they abuse the system or repeatedly ask for a redo, we need to modify the system.

On most occasions, however, our first response is to be merciful. One of the signs of a great intellect is the inclination to extend mercy to others, and all successful teachers are intellectual.

How We Would Want to Be Treated as Adults

This is another criterion to consider. There are many times in which we’ve had something due for a committee, an administrator, or a graduate course, but we were too overwhelmed, tired, neglectful, or immature in our planning to finish the task in time.

As long as we don’t make such delays habitual, it’s usually not a problem, and we’re still held in high regard.

The world can be an unrelenting whirlwind of criss-crossing priorities and urgencies. It’s getting harder to make the most efficient choices and stay in good health, mentally, emotionally, and physically. Offering compassion to others in the midst of this is not only effective, it’s refreshing.

Ask Parents to Sign Original and Request Redo

This keeps them aware of what’s going on. It also prevents the student from begging, “Please let me study this during lunch then retake the test in the afternoon. I can’t take this grade home to my Dad.”

Reserve the Right to Change Redo Formats

There are times when it’s not worth students’ going through the whole project or assessment from the beginning for a redo. For time and sanity’s sake, we may just want to assess the student orally and record the new grade right away.

Instead of a student redoing a large, complex culminating project on the use of imagery in poetry, for example, I might call the student to my desk and ask him or her to find five uses of imagery in each of two different poems, then to explain how the poet used the imagery to invoke feelings and thoughts in readers’ minds. I might ask the student to give me the technical terms we use to analyze poetic imagery, then I might ask him or her to generate a few lines of poetry that incorporate two of those types of imagery.

In ten minutes, I’ve reassessed my student, and I record the new grade in the gradebook.

A Calendar of Completion Will Yield Better Results

It is disrespectful to you and to the student for him or her to spend considerable time restudying the material only to get the same grade or lower. If you can, sit down with the student for a few minutes and work out a successful study plan.

Get practical, too: “What will you need to do on Thursday so you can turn this in to me on Friday?” After the student responds with several suggestions, you continue, “What will you do on Wednesday so that you can do these steps on Thursday so you can turn this in to me on Friday?” Always work backwards to the present day.

“You should have used your time more wisely,” you scold. “All the rest of these assignments are zeros.”

This response is abusive. Most students need interaction with an adult to create a successful calendar of completion. This is also true for students who were out sick or on vacation and are doing make-up work by a certain date. Compassion goes a long way and isn’t soft. It’s tough and requires serious thinking.

Creating a calendar of completion means we set a date by which time the redone work is submitted, or the grade becomes permanent. This is usually one week after the original assignment is returned in my classes, but extenuating circumstances can change that.

Redos and Grades

If a student studies extensively yet still earns a lower grade on the redone work, we can take several actions.

Reconsider the student’s earlier, higher grade. Was it a fluke? Was it a valid indicator of mastery? Something is wrong when a student’s mastery decreases over a few days’ time. In such cases, we need to investigate what happened by reexamining the responses on the earlier assessment and interviewing the student.

When it comes to what grade to record in the gradebook—the higher or lower one—choose the higher grade. In most of life, we’re given credit for the highest score we’ve earned. Many lawyers, driver’s license holders, accountants, teachers, and engineers appreciate this policy.

Don’t average the first and second grade together, either. This is not an accurate rendering of mastery. An analogy with the Department of Motor Vehicles works here: Imagine I’m going for my driver’s license in a state that requires a grade of 80 percent correct on the written exam in order to pass. On the first attempt, I earn 20 percent. This isn’t very good—stay off the sidewalks, I’m driving!

After studying a bit, I go back and earn 100 percent on the written exam. I’d get my license, correct? Sure. If we averaged the two scores, however, I wouldn’t get my license, and I’d have to muddle through a string of 100 percents to finally get my license. We don’t do this to stable, secure adults; why should we do it for humans in the morphing?

No Redos During Last Week of Grading Period

Keep the Original and the Redo Together

Ask students to staple or attach the original task or assessment to the redone version. Sometimes it’s difficult to remember where individual students are in their redo journey. Seeing the original materials helps us determine student growth and keeps gradebook accounting clear.

Our World Is Full of Redos

The decision to allow students to redo work that is poorly done or missing is a tough one. Teachers debate the merits of allowing redos in schools around the world. If we’re basing our decision on the “real” world outside of school, then the answer is clear: Allow students to redo work.

This may run counter to some teachers’ assumptions that in the real world you don’t get “do-overs.” Yet we do.

Pilots can come around for a second attempt at landing. Surgeons can try again to fix something that went badly the first time. Farmers grow and regrow crops until they know all the factors to make them produce abundantly and at the right time of the year. Movie directors? They invented it.

Our world is full of redos. Sure, most adults don’t make as many mistakes requiring redos as students do, but that’s just it—our students are not adults and as such, they can be afforded a merciful disposition from their teachers as we move them toward adult competency.

Related Rick Wormeli resources:

► Rick Wormeli: Redos, Retakes, and Do-Overs, Part One (YouTube)

► Rick Wormeli: Redos, Retakes, and Do-Overs, Part Two (YouTube)

► Rick Wormeli: On Late Work (YouTube)

► Rick Wormeli: Standards-Based Grading (YouTube)

Rick Wormeli was among the first National Board Certified teachers in America. His education career spans 35 years – teaching math, science, English, physical education, health, and history and coaching teachers and principals. He is a columnist for AMLE Magazine and a frequent contributor to ASCD’s Education Leadership magazine.

Thank you for sharing these wonderful ideas for redos. I have tried two different approaches with my 8th grade math students to keep it varied — and offer these to all students on assessments.

The first is the traditional redo with a different quiz after they have reviewed the questions they missed or come in to see me if needed.

The other is a “second attempt” – this is the same assessment – but the students are asked to correct the questions they missed (getting them to analyze the problem or their work a bit more). This one is done during the assessment period – and works well for math because they are correcting their own mistakes while they are testing. The students are excited to see their scores improve and it is teaching them to persevere with more difficult problem-solving situations.

I know every teacher does things differently in our building – but most are using the idea of redos in a positive way. The differences in our approaches are a little confusing for students at the beginning of the year – but I think the most important thing is to be fair to all students and offer everyone the same opportunities to improve and learn.

Thanks again–

Anne Shafer

Shore Middle School

Mentor Schools

Curious about your thoughts on high school…

I am at a high school that requires students redo all mastery assignments until the score reaches 90% — formative assessments not necessarily. Additionally, there are no true time limits maintained, thus teachers are required to allow students to redo September assignments weeks or even months later — might be in December along with the final exam. Thus grading and assessment creation / modification is incredibly burdensome. Ideas to take to admin to make this a fair, educationally appropriate system for students and also a fair and sustainable system for teachers would be greatly appreciated.

What are your feelings about redos at the elem level when you know students don’t care and parents offer.no support?

Thank you for confirming the practice that I’ve used for a number of years. I allow redos for all tasks. Students are encouraged to use a different approach for the revision: study differently, attend to teacher comments on an essay, etc. All redos are capped at 88%. In other words, in order to earn a grade in the “A” range, a student needs to achieve it on the first try. Any performance on a redo > 88% is commended, but an 88% is recorded in the gradebook. This eliminates “grade grubbing” and students memorizing the answers to the two items on the quiz they got wrong. This way, redos give a chance to students who really did not achieve mastery on the first try and need to identify different strategies to find success.

Redos have always been hard for me as an art teacher. I will try your ideas. Thank you.