Stop Student Plagiarism Before It Starts

A MiddleWeb Blog

I do not enjoy being the plagiarism police with my middle school students. For me, detecting plagiarism (and determining consequences) takes more energy than proactively planning assignments that don’t lend themselves to copying.

I do not enjoy being the plagiarism police with my middle school students. For me, detecting plagiarism (and determining consequences) takes more energy than proactively planning assignments that don’t lend themselves to copying.

Here are some steps I take to prevent plagiarism before it begins. These may not make the assignment “plagiarism proof,” but they will certainly make copying more difficult.

► Discuss the idea of plagiarism on a personal level.

Have a conversation with students about how annoying it is when someone copies them on a superficial level such as hairstyle, clothing, catchphrases, etc. You could extend this to how they feel when a friend or a sibling “borrows” something of theirs because they really like it, but then claims it as their own or never gives it back. This is a normal fact of life, but that doesn’t make it acceptable.

Then, take the discussion to a deeper level and discuss how pupils would feel if someone stole the product of their hard labor such as a research paper, art project, essay, or a story they wrote. Middle school students are all about what is fair, and they will most likely share how upset they would feel if someone else got the credit for their work.

If they are having difficulty relating to the topic on a personal level, perhaps share some current plagiarism scandals in the news, or historical cases such as those that were filed against Helen Keller, Coldplay, or Martin Luther King.

► Explicitly teach the skills of paraphrasing and summarizing.

It is not enough to tell students to “put it in your own words” or “don’t copy” because many don’t know what else to do. Often, they are not deliberately trying to plagiarize; they just don’t know how to document information.

Many think that just replacing a word in the original text with a synonym is sufficient. Others will just lift specific phrases, delete content from in between, and say that they didn’t copy word for word so it is not plagiarism.

I find that sharing many examples of correct and incorrect paraphrasing goes a long way in helping them understand. In addition, focusing on finding the meaning in the original text and then restating it as if explaining or teaching it to another student helps cement the concept.

My students use an online note-card program called Noodle Tools. When they are doing initial Internet research, I have them find as many sources as they can.

The beauty of this system is that I can see their note cards during our writing conference to see if they are on the right track.

It doesn’t have to be boring. For example, when I teach summarizing, they enjoy it when I challenge them to take several paragraphs of text and summarize them in exactly 12 words. This forces them to focus on the essential content.

Another activity that is fun is the “Incredible Shrinking Article.” I hand out a copy of an article to each student. I have them highlight what they consider to be the most important sentences in the article. Then, I have them cut it down to 10 sentences.

Next, I have them compare their chosen 10 with the other members of their group. The group then needs to determine five of these sentences that they feel contain the most crucial information. Finally, as a group, they summarize the gist of the article into one or two original sentences.

► Incorporate some form of collaboration, discussion and feedback into the project.

For example, try a partner paraphrase/summarize activity. One student should have the original text. This student reads a paragraph or section of the article to the partner, but the partner can’t see the original.

► Add a personal reflection component…

either within the assignment itself, or thinking back on the process of completing the work. It would be nearly impossible for students to find already produced work that has a section tying the material to experiences like their own.

► Connect the assignment to something you have specifically done in class.

Incorporate a news article or novel they read, a video clip you showed, or a class discussion into the final product. This means that they need to generate original thought because the odds of finding the exact same configuration of original text and supplemental material are infinitely small.

► Break the assignment into chunks and have required check-ins.

In addition, some of the components of the final product could be completed during class time. This makes it easier for the teacher to monitor their progress and address any questions. It also reduces the chance that the student will be completing the entire paper the night before.

► Along with chunking, confer with the student throughout the process.

This will allow you to determine to what extent they understand their topic. For instance, you could ask them what surprised them most from their research thus far. Ask them to pretend they were teaching another person about their work and have them summarize what they would say. This will allow the teacher to know if they even understand their topic or are way off base.

► Designate one specific source they must use – ideally a current or uncommon one.

If students are studying the American Revolution, for example, share a few picture books, such as Independent Dames by Laurie Halse Anderson or The Scarlet Stockings Spy by Trinka Hakes Noble, and require these to be addressed in the final product. If they are studying something more contemporary, newsela.com is a rich source of quality material.

► Add a component that cannot be copied.

For example, students could interview an expert, document something from a field trip, build a handmade visual aid, or design an oral presentation. This fits into the spirit of 21st century education and is more engaging than merely looking up facts.

► Most importantly, design assignments utilizing higher-order thinking skills and creativity.

When students are required to explain, problem solve, evaluate, hypothesize or compare, it is nearly impossible for them to find this kind of assignment online from which to borrow. One sure rule of thumb regarding designing any assignment: If the work can be copied somewhere, it will be.

Therefore, think ahead to develop a paper or project that necessitates, at the very least, applying the knowledge.

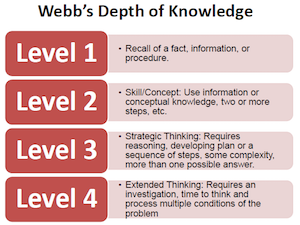

Better still, start your assignment design at the highest levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy or Webb’s Depth of Knowledge levels. These kinds of assignments don’t lend themselves to the regurgitation of facts and demand complex thought.

This will be more motivating to students and will force the content to be original. To illustrate: rather than writing a biography of a president (a sure recipe for plagiarism), have them write a mock letter to the post office or the White House persuading officials to designate a new stamp or holiday to be held in that president’s honor due to his many accomplishments.

As our students become accustomed to generating unique end products for assignments that are innovative, multimodal, and require critical thinking, I believe that the incidents of plagiarism in our classrooms will be greatly reduced.

Note: I developed this article from a short post that appeared at the SmartBrief blog in 2014.

This is a very helpful post on an important subject. I also think it is vital to design question-based (as opposed to topic-based) writing assignments, as they compel students to EXPLAIN instead of LISTING (and copying) facts. I’ve blogged on this point here: Too Many Topics?! Try the DBQ Approach to Research Papers