Should We Try to Make History “Relevant”?

A MiddleWeb Blog

I heard it so often, in fact, that it became clichéd.

Most history teachers are aware that our subject is among those most likely to be described as “boring” by students.

Try googling “history and boring” or “why students hate history,” and you will see what I mean. Or read this blog post by Glen Wiebe for a thoughtful commentary on the problem.

I am biased. I think history is without a doubt the most important, relevant topic that students will ever study. It is the basis of good citizenship and a powerful tool to strengthen critical thinking and problem solving. And it has more good stories and drama than ELA.

So how do we overcome the perception that history is dull? In the post I reference above, Glen Wiebe quotes James W. Loewen, the author of the highly-regarded book Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, who says the problem is not history itself, but the way it is taught.

So how do we teach history that’s not boring?

First off, let’s scrap the word “relevant.” The word suggests that what we teach must be either practical (help students get a job or learn a skill – worthy goals, but what about learning for its own sake?) or connect directly to their lives. I’d like to focus on this last point for a moment. If education has a purpose, shouldn’t it help students get beyond their current lives? Shouldn’t we teach students about the world beyond their typically narrow experiences?

If we think we can only teach something by connecting it to students’ experiences, and all that they have experienced is a typical middle-class American life, then what do we do?

And for those students who are decidedly not middle class and have experienced poverty, crime and lack of opportunity, then isn’t it perhaps even more important to expose those students to the larger world?

The risk of oversimplification

Most important, making history “relevant” to students risks oversimplifying history. Imagine, for a moment, trying to make your students appreciate what it was like for Jewish families in the late 1930s and early 40s as they tried to escape Nazi oppression. Or what it would be like to leave your home in Seattle during World War II because you were of Japanese ancestry. Or what it was like to live in the American South during the years before the Civil Rights movement.

Consider the two ideas below:

- Ask students to think about a time they moved or went on a trip somewhere.

- Think about a time when you felt discriminated against or left out.

There are quite a few pedagogical flaws with such an approach. Moving to another town because your mom got a new job is not anything like fleeing for your life or being evicted from your home in the middle of the night at gunpoint (or in the daytime because of an Executive Order). And most kids know this.

Even if some students don’t know this, a teacher who asks for this sort of analogy from his or her students risks suggesting that it is an appropriate analogy. The teacher risks minimizing the realities of the historic situation. The teacher risks oversimplifying the history.

I think the reason for their interest is that all of these topics deal with a fundamental philosophical issue: justice. And there is nothing that grabs the interest of an adolescent more than justice and the perception that something is unfair.

Adolescents are constantly being told what to do by adults at the same time they’re beginning to feel more independent and capable – and developing opinions of their own. It makes sense that questions about justice or the lack of it would be issues that grab their attention.

Meaningful connections more than “relevance”

So I’d like to propose that we worry less about making history relevant and more about making it interesting or meaningful. Sarah Cooper has written on this topic both in her book, Making History Mine: Meaningful Connections for Grades 5-9, and in this MiddleWeb blog post, where Sarah offers eight ways to make history more meaningful.

I want to elaborate on four of her approaches:

- examine different points of view,

- find patterns in the past,

- connect the past to the present, and

- evaluate ethics.

All four of these goals can be met by taking the topics of history and connecting them to broader themes or essential questions raised. For example, the Civil Rights movement raises a number of important questions that are applicable not just to that movement, but to any movement.

- Does change come from the bottom up? Or the top down?

- Is it better to work with the system; i.e., negotiate and compromise? Or protest against the system?

- What is the most effective form of protest? Peaceful? Or is it only when violence breaks out that people pay attention?

- Integration? Or separation?

Melding these questions into the unit offers the potential to connect issues of the past to the world today. They force students to wrestle with ethical issues and different points of view. And they can help students recognize patterns. For example, how does the issue of racial equality relate to earlier questions about Reconstruction? Or assimilation of Native Americans or immigrants?

Studying the less “juicy” periods of history

At this point you might be thinking, well, this is all fine and well for the “juicy” parts of history like Civil Rights. But what about the older, less exciting parts of history?

The first thing that comes to my mind is the period I always found difficult to make interesting to students: the 1790s and the conflicts between Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and the developing political parties in the young nation.

Along with U.S. history teachers everywhere, I now owe a big thank you to Lin-Manuel Miranda for changing that with his musical, Hamilton. Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters have written eloquently about this on an earlier post here at the Future of History blog. That musical has much to teach us about making “dry” history anything but.

From CBS Sunday Morning

One of the lessons we can learn from Hamilton is that we can draw out themes of history and make it universal. In this case, portraying Alexander Hamilton as a poor, scrappy immigrant wanting to make good.

Relating past to present

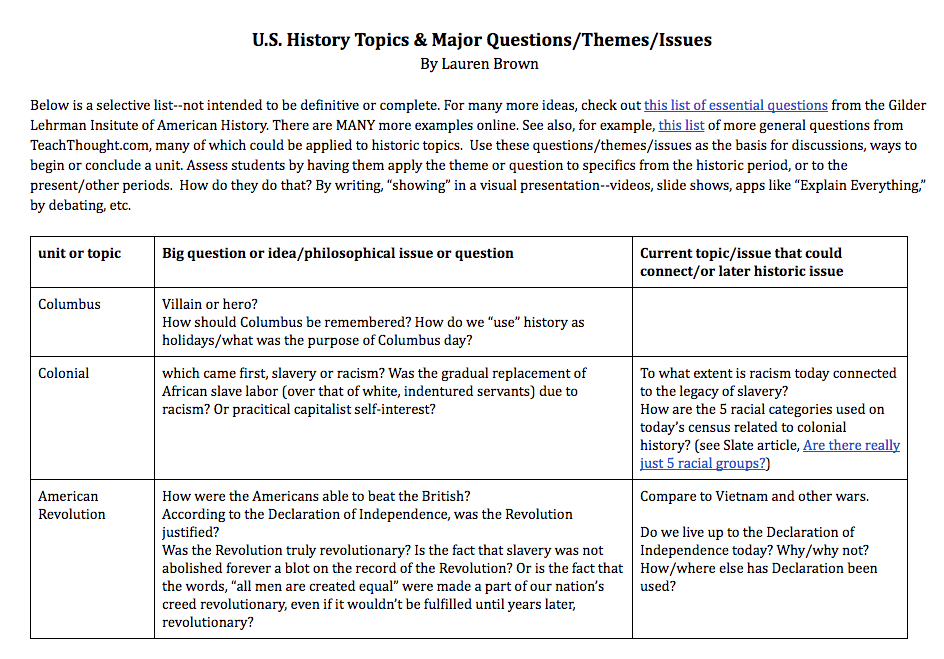

I have created a chart as a way to help get newer teachers thinking about these kinds of questions. It should be considered only a starting point, as it hardly includes every topic in American history. Check it out here.

It is not always easy to keep such broad questions in mind once the school year starts and the rush begins to cover content and standards and prepare students for standardized tests.

But trying to think about these questions for each unit or topic we teach will help us solve the bigger problem: how to keep our students attentive and engaged and interested. If we focus on these broader questions, our assessments (and our teaching) will move away from the name/date/fact based study of history that kids find so boring.

A very thoughtful article. Thank you!

Relevance, and the attempt to achieve it, too often leads to kids thinking that the past and the present are the same thing. It also often leads to some really poor history teaching. I think your advice to focus on engagement and interest is very important for teachers to consider.

Good point about kids mixing up past and present, which is why chronology and cause/effect matter so much. (For more on that, everyone should check out Bruce Lesh’s book, Why Won’t You Just Tell Us the Answer? https://www.stenhouse.com/content/why-wont-you-just-tell-us-answer

Lauren, thank you for pointing out so clearly that analogies between history and students’ lives can often be overly simplistic. Focusing on justice in history is an excellent motivator. I’m glad you found useful my book’s focus on making history meaningful, too. Nice piece!

Excellent thoughts. Thank you!

This is great! Do you have any ideas about how to connect ancient history to current events? I am really wanting to talk about the election results with my 6th grade world history class but am struggling as to how to make the connection. I just finished up ancient Mesopotamia, and we are moving into Egypt.